A group of U.S. students has smashed a series of world records after launching a "homemade" rocket farther and faster into space than any other amateur rocket. The student-made missile soared 90,000 feet (27,400 meters) beyond the previous record-holder — a Chinese rocket launched more than 20 years ago.

The record-breaking rocket, named Aftershock II, was designed and built by students at the University of Southern California's (USC) Rocket Propulsion Lab (RPL) — a group run entirely by undergraduate students. The students launched Aftershock II on Oct. 20 from a site in Black Rock Desert, Nevada. The rocket stood about 14 feet (4 meters) tall and weighed 330 pounds (150 kilograms).

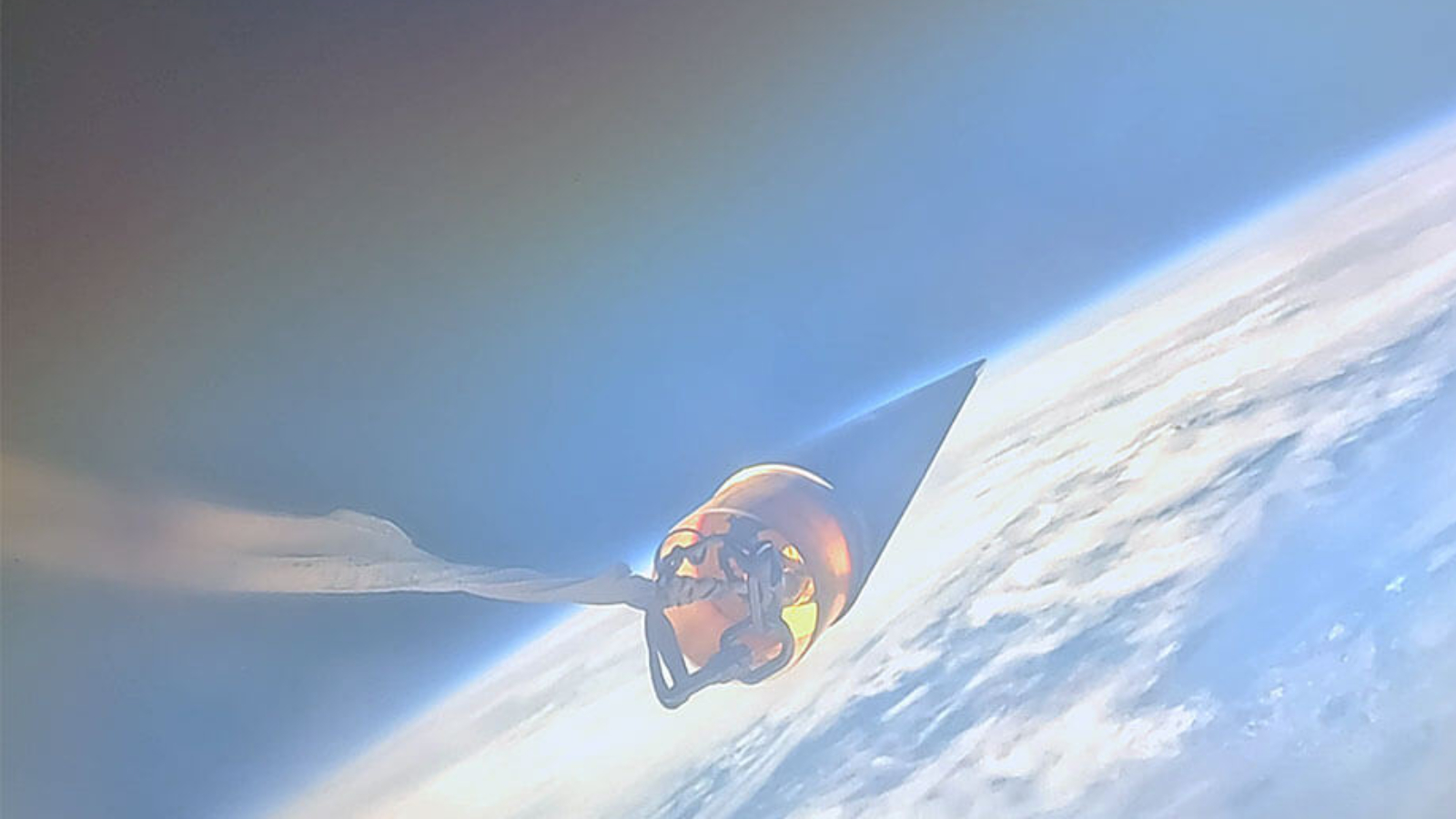

The rocket broke the sound barrier just two seconds after liftoff and reached its maximum speed roughly 19 seconds after launch, the RPL team wrote in a Nov. 14 paper summarizing the launch. The rocket's engine then burned out, but the craft continued to climb as atmospheric resistance decreased, enabling it to leave Earth's atmosphere 85 seconds after launch and then reach its highest elevation, or apogee, 92 seconds later. At this point, the nose cone separated from the rest of the rocket and deployed a parachute so it could safely reenter the atmosphere and touch down in the desert, where it was collected by the RPL team for analysis.

The rocket's apogee was around 470,000 feet (143,300 m) above Earth's surface, which is "further into space than any non-governmental and non-commercial group has ever flown before," USC representatives wrote in a statement. The previous record of 380,000 feet (115,800 m) was set in 2004 by the GoFast rocket made by China's Civilian Space Exploration Team.

During the flight, Aftershock II reached a maximum speed of around 3,600 mph (5,800 km/h), or Mach 5.5 — five and a half times the speed of sound. This was slightly faster than GoFast, which had also held the amateur speed record for 20 years.

Related: 15 of the weirdest things we have launched into space

But elevation and speed were not the only records Aftershock II broke. "This achievement represents several engineering firsts," Ryan Kraemer, an undergraduate mechanical engineering student at USC and executive engineer of the RPL team who will soon join SpaceX's Starship team, said in the statement. "Aftershock II is distinguished by the most powerful solid-propellant motor ever fired by students and the most powerful composite case motor made by amateurs."

The record-breaking launch is the latest success to come from RPL. In 2019, another group became the first student-led team to launch a rocket past the Kármán line — the imaginary boundary where space officially begins, Live Science's sister site Space.com previously reported. Aftershock II is only the second student rocket ever to reach this milestone.

To create their record-breaking rocket, the Aftershock II team used new advancements in thermal protection, which is critical when a rocket is traveling at hypersonic speeds (above Mach 5). The students coated Aftershock II in a new type of heat-resistant paint and equipped it with titanium-coated fins, which replaced carbon-based parts used on previous models.

"Thermal protection at hypersonic speeds is a major challenge at the industry level," Kraemer said. The upgrades the team made "performed perfectly, enabling the rocket to return largely intact." However, the heating effect was so intense that the titanium fins turned from a silvery color to blue, due to a process known as "anodization," in which the metal reacts with atmospheric oxygen to create a layer of titanium oxide, he added.

The team also designed a new control unit for the rocket, known as High Altitude Module for Sensing, Telemetry, and Electronic Recovery (HASMTER), which tracked the rocket's flight and deployed its parachute.

The researchers overseeing the RPL team were impressed with the students, who received minimal help from their teachers.

"This is an exceptionally ambitious project not only for a student team, but for any non-professional group of rocket engineers," Dan Erwin, an aerospace engineer and chair of the USC Department of Astronautical Engineering, said in the statement. "It's a testament to the excellence we seek to develop in our emerging astronautical engineers."