Uncommon Courses is an occasional series from The Conversation U.S. highlighting unconventional approaches to teaching.

Title of course:

Campaigns and Elections, in Theory and Practice

What prompted the idea for the course?

I noticed many of my students, including those interested in political science, had never actually engaged in politics beyond voting. I also saw that many of the clubs and activities that helped me make friends when I was a college student seemed to have withered during the COVID-19 pandemic. I wanted students to have an opportunity to get to know each other, see how politics works in practice and get something useful on their resumes.

What does the course explore?

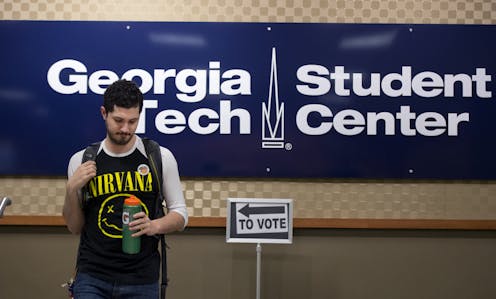

Every student participates in an election in some way. They can help register people to vote, volunteer for a campaign, be nonpartisan election workers or serve as poll watchers. They can volunteer for any kind of campaign, from the presidential election all the way down to local races, where students might be interacting directly with candidates. We’ll spend most of the class processing what is happening on the campaign trail: the good, the bad, the ugly and the absurd.

Why is this course relevant now?

Today’s students face serious headwinds. They’re inheriting historic political and social divisions that are compounded when people tell them not to trust anyone else. They’re also strikingly lonely. I think that the only way out of the cynicism and distrust is by engaging, participating and understanding how the system does and doesn’t work.

What’s a critical lesson from the course?

I want students to learn that they don’t have to be what gamers call NPCs – nonplayer characters – in politics. They’re just as capable of participating in democracy and leading their communities as the folks already running the show.

What materials does the course feature?

The only book for the course is “Campaigns and Elections” by Vanderbilt University political scientist John Sides and three of his colleagues. This great text is both practical and rooted in political science research about elections. As a group, we also select podcasts to listen to, news articles to read and videos to watch.

Because we’re in Texas, students will keep up with what’s going on here by reading The Texas Tribune and listening to the Texas Take, a political podcast from the Houston Chronicle. They’ll also learn the inside baseball of national politics through media outlets such as The Hill, Politico and Axios.

I also make sure they know about AllSides.com, a website that shows how different media outlets are covering the same story. I’ve found AllSides to be exactly what distrustful students have been looking for. During an election cycle, it helps them see what narratives campaigns are crafting from the news of the day.

What will the course prepare students to do?

I hope students take away two key lessons from this class that may seem contradictory. First, it’s easy to engage in and volunteer for campaigns. Second, it’s hard to set up a campaign or run an election well.

When you don’t know how things work, everything can look like a conspiracy. I hope that by seeing how the system works, students will gain confidence in the U.S. electoral system. It’s not perfect. But it’s full of mostly well-intentioned people trying to make things a little more perfect. And students have the opportunity and capacity to do the same.

Mark C. Hand does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.