In an otherwise normal football season, two California high schools abruptly canceled the remainder of their games for the same reason. Players on both teams participated in troublesome acts of racism.

In October 2022, Amador High School in Sutter Creek ended its season after school officials learned that several players joined a Snapchat called “Kill the Blacks.”

In nearby Yuba City, members of the River Valley High School football team produced and filmed a modern day slave auction.

In the film, three teammates – all young Black men – were offered for sale.

“They needed another person to be in the video, and being the only Black person left in the locker room, they all turned to me,” one of the Black students said. “I made it clear I didn’t want to do it and tried to leave, but wasn’t able to.”

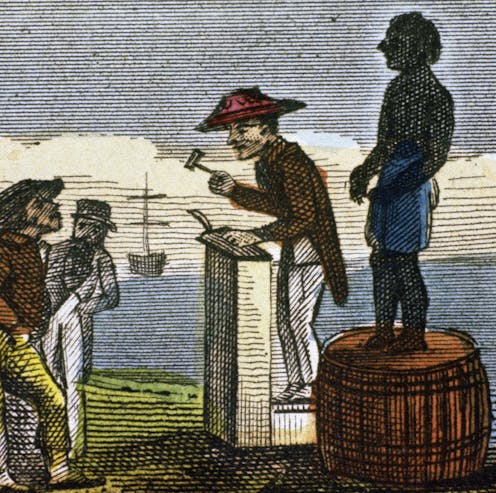

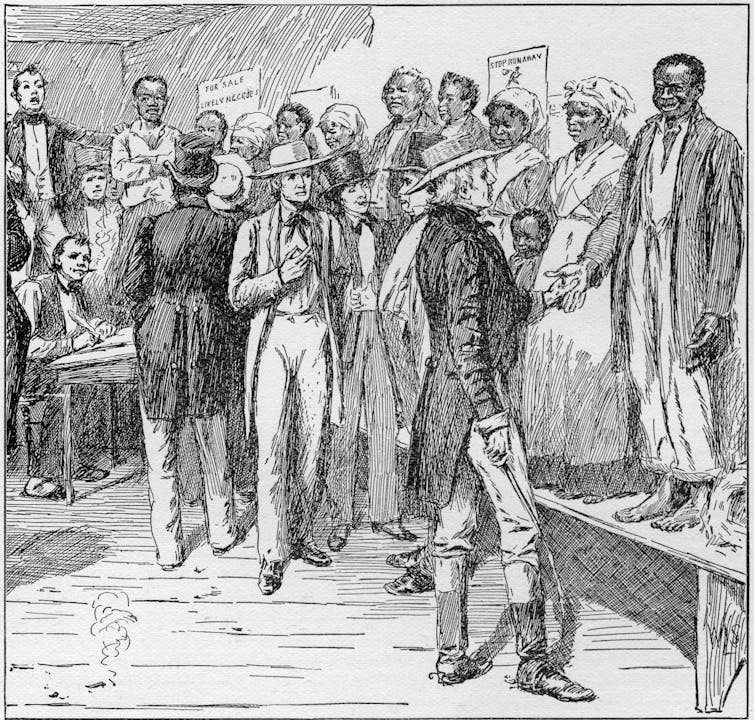

Clad in their underwear and with their eyes downcast, the three were paraded through the locker room and put on an auction block. At least one of the Black teens had a belt representing a noose looped around his neck.

Their white and Latinx teammates feverishly bid on them. Even through the lens of the video camera, the “mock” enslavers’ excitement and frenzy were palpable.

Many are upset with the Black youth for participating in their own degradation. I understand that. But as I outline in my recent book, “Bodies Out of Place: Theorizing Anti-blackness in U.S. Society, I also understand that "public degradation ceremonies are meant to debase and dissuade Blacks from walking in their full humanity, as full citizens.”

Less than 2% percent of the students at River Valley High – 31 out of the total 1,801 – identify as Black.

These numbers render Black students both extremely visible and invisible at the same time.

In my view, the slave auction operated as a perverse public performance used not only to reinforce the Black students’ inferior status in their own minds, but also to signal the same to those watching.

What lies underneath the mockery

A Boston University teaching guide defines the “hidden curriculum” as an amorphous collection of implicit cultural messages of the dominant culture. These unwritten rules reinforce an often unspoken social order in which people of color are subordinate.

The hidden curriculum refers not only to unwritten rules, but also “unspoken expectations” that serve as “unofficial norms, behaviors and values.” These norms become institutionalized. As sociologists Glenn Bracey II and Wendy Leo Moore write, “Although the norms are white, they are rarely marked as such.”

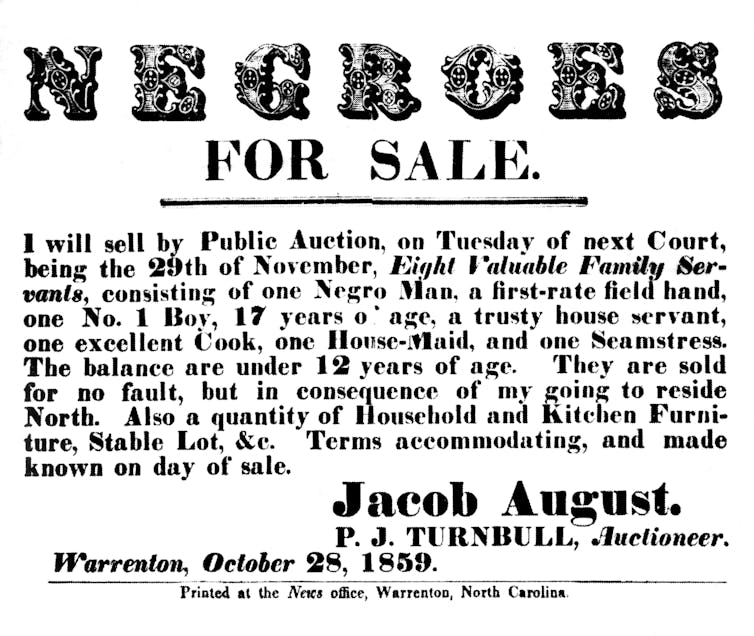

Mock slave auctions are not rare occurrences.

In May 2022, white middle school students at Chatham School District in North Carolina held one by staging the sale of their Black classmates.

One of the parents, Ashley Palmer, posted on Facebook that her son had been “sold” by his classmates.

“His friend ‘went for $350’ and another student was the Slavemaster because he ‘knew how to handle them,’” Palmer wrote. “We even have a video of students harmonizing the N word. Since when were children so blatantly racist?”

In another incident, students at Newberg High School in Oregon participated in a yearlong virtual slave auction called “Slave Trade” that was uncovered by their parents in 2021. On the chat, they targeted Black students and used homophobic and racist slurs while joking about how much they would pay for their Black classmates.

These patterns continued in 2021 when students in Texas created a social media group called “N***** Auction” and pretended to auction off their Black peers.

Not all of the auctions are held on virtual platforms.

In 2016 in Barrington, Illinois, for instance, a “mock slave auction” was staged by Barrington High School students in order to create what they described as “school spirit” during an event meant to bring students from Chicago and the suburbs together.

Why it all matters

Group performances not only serve as a bonding experience among members, but they also reinforce an imaginary social hierarchy that harks back to the days of Jim Crow at the turn of the 20th century and legal racial segregation.

These performances convey a message about a sense of belonging. Without using the specific words, the acts suggest to Black students in stark images that their status is marginal at best.

It is important to connect the past and present, as Yuba City Unified School District Superintendent Doreen Osumi did in a statement obtained by CNN.

“Reenacting a slave sale as a prank tells us that we have a great deal of work to do with our students so they can distinguish between intent and impact,” Osumi wrote. “They may have thought this skit was funny, but it is not; it is unacceptable and requires us to look honestly and deeply at issues of systemic racism.”

For their part in the mock slave auction, the Black students at River Valley High School issued apologies.

Each received a three-day school suspension – a punishment that proved harsher than that issued to some of their non-Black counterparts, according to Greater Sacramento NAACP President Betty Williams. Though it’s unclear what the punishments were for white students, Williams said they “were not equitable in their distribution.”

I understand Williams’ frustration. In my mind, it could be argued that the onlookers were no more culpable than the hundreds and sometimes thousands of whites who packed picnic baskets and gathered after church to watch a Black person get lynched.

“I am hurt that the school moved so quickly to punish us instead of taking their time to understand the situation better,” said one of the Black students.

“But looking back I wish I had done more to stop it,” the student wrote. “When the video was made I was not feeling good about it and I froze. I wanted to get it over with so I could get to practice.”

While it remains unclear why the team thought holding a mock slave auction was a good idea, one thing is clear: The harm caused by their actions continues to reverberate.

This article was updated to correct the fraction of Black students at River Valley High School.

Barbara Harris Combs does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.