Most people today are coping with the rising cost of living individually: cost cutting, looking for a better paid job, taking on “side hustles”, and so on. But not so long ago, many workers globally and in Aotearoa New Zealand approached the same problem in far more collective ways.

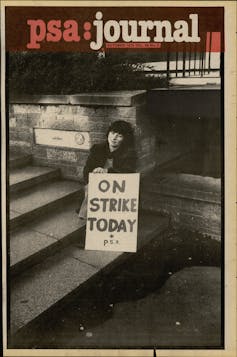

From the late 1960s to the early 1980s – sometimes referred to as “the long 1970s” – the union movement used strikes to combat the effects on workers of chronic inflation and a deep economic crisis. These were often successful, both in Aotearoa and around the world.

In many ways, the long 1970s were similar to today, a turbulent era of wide-ranging transformation, social polarisation and economic decline. After the long post-war economic boom, the so-called “golden age” of capitalism came to a halt in the late 1960s. A long-term social and economic decline set in after the oil shocks of the 1970s.

Largely in response to this, strike levels reached historic peaks in many countries. As British journalist Andy McSmith wrote of the UK’s 1978-1979 “winter of discontent”, it was simply “irrational not to strike”, given how inflation was eroding pay packets. In Aotearoa New Zealand, for example, inflation averaged 11.5% in the 1970s and peaked at 17.2% in 1980.

Collective resistance wasn’t only organised in workplaces. There were also consumer campaigns such as the Campaign Against Rising Prices in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly organised by (unpaid) women domestic workers, and often supported by unions.

Many unions mobilised to obtain better pay – often because of workers’ demands over declining real incomes. Millions of workers around the world struck to keep their wages level with inflation, in many instances securing pay increases above inflation rates.

Defending living standards

In Aotearoa New Zealand, as historian Ross Webb has argued, the Federation of Labour (FOL) adopted a largely successful strategy of “defending living standards” from the late 1960s to about 1984. They argued that employers and governments were trying to place the burden of the recession on workers and their families.

Union tactics were reasonably canny. They did not simply butt heads with employers set on reducing costs, or governments intent on restricting wage increases through incomes policies.

Instead, they contested the assumption of employers and politicians that inflation was mainly caused by wage increases (the wage-price spiral), rather than a result of companies raising prices, profiteering and passing on the cost of the oil shocks.

There were two tactics in particular that don’t seem to exist in Aotearoa today. The first was targeting stoppages against a particular employer. Once a breakthrough was achieved at one workplace, unions would ensure the gain was made into a broader industry, regional or national standard. Targeted strikes were not as costly or as risky as national or industry-wide strikes, with striking workers supported through weekly union levies.

The second tactic involved broad, nationally-coordinated, cross-union mobilisations. These included general strikes (either city-wide or national) and nationwide demonstrations. These solidarity actions generally focused on unsympathetic or intransigent governments intent on clamping wage increases.

When the Arbitration Court announced a nil general wage order in 1968 (meaning wages couldn’t rise), despite inflation running at about 5%, the FOL organised a limited campaign of targeted strikes against certain employers. Its Wellington Trades Council held a one-day, general, city-wide strike and a stormy protest outside parliament.

General strikes and export bans

Targeted stoppages were often highly effective, especially in strategic industries where profits and production could be quickly halted. For example, meatworkers banned all meat exports to counter the nil wage order. This was the country’s biggest export at the time, accounting for 40% of export revenue.

The export ban, together with many other stoppages, quickly brought results. Workers were granted a 5% increase nationally, just two months after the nil order was announced.

In 1979-1980, a union campaign successfully saw the repeal of the 1979 Remuneration Act, imposed by Robert Muldoon’s authoritarian populist-right government and which enabled the state to unilaterally lower negotiated wage increases between employers and unions.

Read more: Strikes: how rising household debt could slow industrial action this year

The campaign involved a one-day national general strike in 1979. Some 340,000 to 400,000 workers (75-80% of the FOL’s membership) participated, according to reasonably reliable estimates. It was the most well-supported strike in local history, followed in 1980 by a successful three-month strike by paper mill workers at Kinleith that gained substantial national support.

The final nail in the coffin for the Remuneration Act was the living standards campaign organised by the FOL and the Combined State Unions in 1980. Large protest marches were held around the country, including one that attracted up to 45,000 people during a three-hour, city-wide stop-work action in Auckland.

There were also smaller shop-floor strikes aimed at achieving localised pay agreements to keep up with inflation. These often resulted in piecework or bonus payment schemes, or allowances for clothes, boots and working in dirty or dangerous condition. They all helped enormously with take-home pay.

Read more: Debate: The forward march of labour restarts with historic strikes in France and the UK

Disputed strategies

These actions drew strong reactions from employers, the state, and from some sections of the community. Conservatives – such as those who took part in the “Kiwis Care” march in 1981 – claimed strikers were greedy, disruptive, destroying the “national interest” and holding the country to ransom. Yet the law-and-order measures employed to contain or repress strikes usually just inflamed unrest.

A more effective response came in the form of economic restructuring and de-industrialisation in the 1980s. Neoliberals argued strikes squeezed profits and production, and restricted management’s “right to manage” the factory and office floor. Employers and politicians used various tactics, such as factory closures, to successfully break unions and undermine workers’ power.

While inflation was tamed in Aotearoa by the early 1990s, it came at the expense of dramatically increased class inequality.

Read more: Recent pay rises suggest that collective bargaining may be on the way back

Worker resistance to the cost-of-living crisis in the long 1970s is still a polarising and contested subject. Probably the dominant view, voiced by the neoliberal right as well as some on the moderate left, is that workers caused their own demise by striking too much.

Some argued that unions had adopted an “immature” conflict-based strategy that could never win, and that neoliberal restructuring was the inevitable response and outcome. Such a view tends to demonise the strike-prone 1970s as the “bad old days” when supposedly thuggish “unions ran the country”.

But it’s overly simplistic to blame workers for simply trying to keep their pay up with inflation after negotiation strategies failed. Those on the activist wing of unions would counter by arguing workers fought back en masse in the long 1970s to defend living standards. But they were simply defeated in the 1980s by more powerful global and local forces.

The diminished collective

Globally, strikes are perhaps back in vogue. In early 2023, there have already been a “mega-strike” in Germany, a “protect the right to strike” action in the UK, and mass strikes against the raising of the pension age in France. In Aotearoa, teacher unions have mounted a rare coordinated strike. As economic problems deepen, it’s likely more will occur.

So far, however, these strikes against the cost-of-living crisis have not been as large or as widely supported as those of the long 1970s. In high-income countries, strike levels today are generally nowhere near the peaks of that period.

This is, of course, directly related to the astonishing decline of union membership since the 1970s. As a proportion of the whole workforce, union membership in Aotearoa has fallen from a peak of 57.5% in 1979 to 17% in 2021. Strikes are therefore limited to a minority of the workforce, especially in the underfunded public sector.

Little wonder, then, that most people these days are coping with soaring costs by taking individual rather than collective action. It’s also one of many reasons why so many feel powerless to effect deeper and lasting change.

Toby Boraman receives funding from the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund. He is a member of the Tertiary Education Union.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.