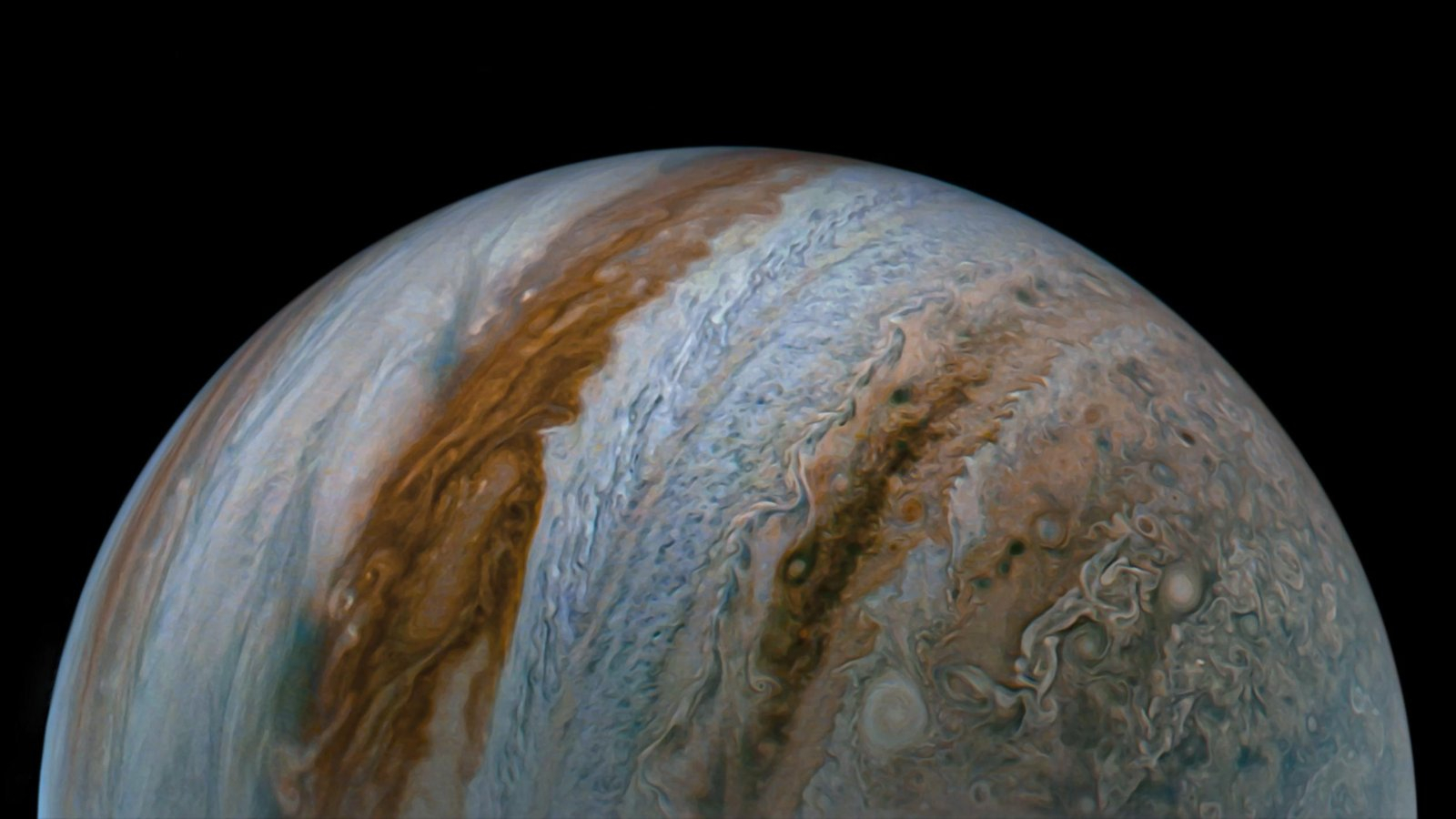

The mysterious workings of Jupiter's intense magnetic field are coming to light, thanks to a tiny jet buried deep in the gas giant's atmosphere. Every four years, this jet appears to fluctuate like a wave.

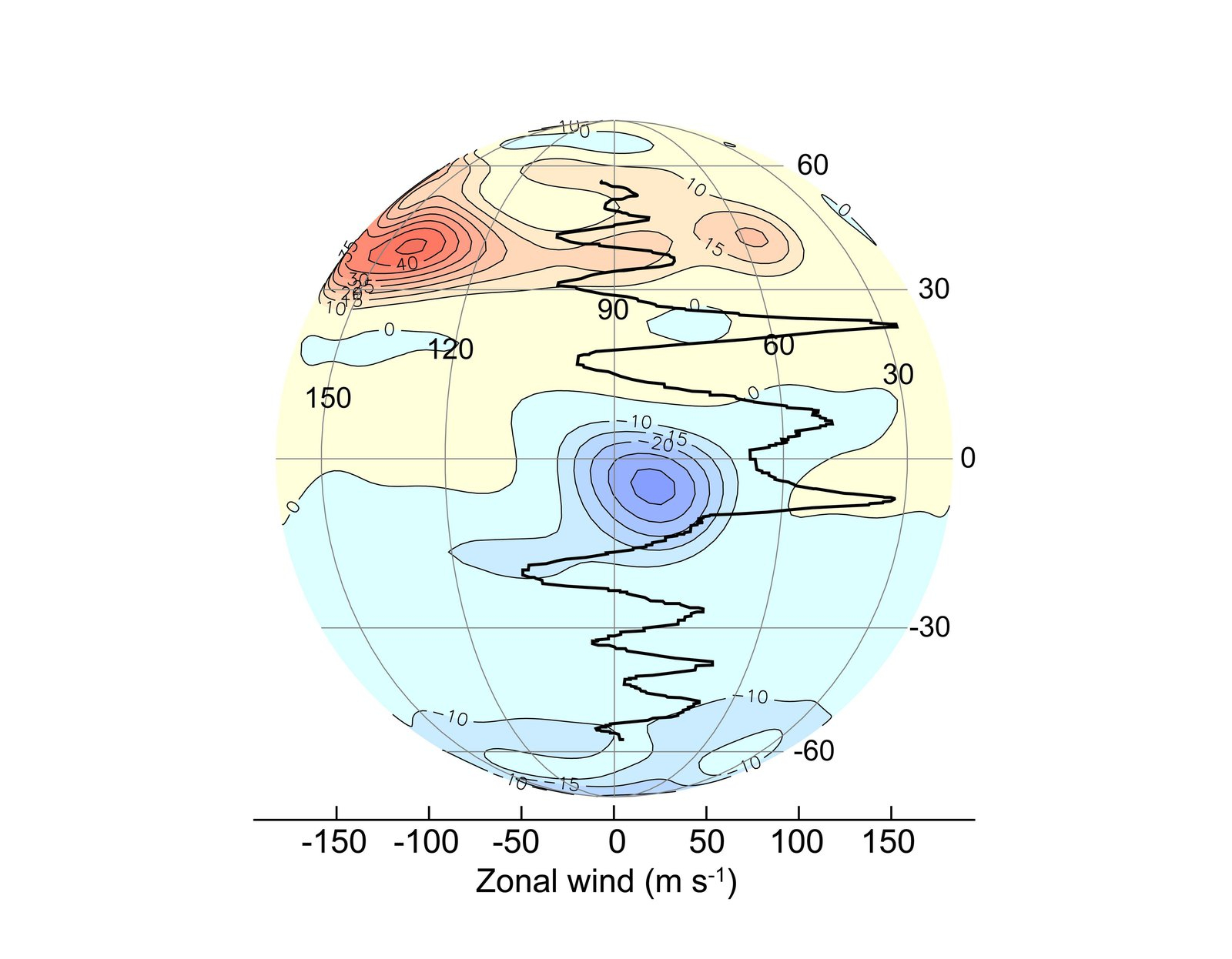

While it's not yet clear what drives this atmospheric jet, new findings reveal some clues about the invisible, complex workings of an intense area of magnetism near Jupiter's equator, dubbed the "Great Blue Spot." This region isn't actually blue; the name comes from the color scale scientists use to build maps of Jupiter's magnetic field. Unlike Earth's magnetic field, the gas giant's field is not symmetric with its rotational axis — this asymmetry is so pronounced, in fact, that the Great Blue Spot can even be likened to a second south pole poking out from the planet's equator. It also appears part of the region is getting swept westward by one jet while other parts are being tugged at by winds flowing eastward.

"It's a mystery," Yohai Kaspi, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and a co-investigator of NASA's Juno mission, told Space.com "We don't know why that place has that kind of an anomaly."

Related: Jupiter's Great Red Spot turns blue in new ultraviolet view from Hubble Telescope (photo)

In a paper published Wednesday (March 6) in Nature, however, scientists may have offered some more insight into the Great Blue Spot. They used data sent home from the Juno probe, presently investigating Jupiter, as it had mapped the Great Blue Spot during a series of targeted flybys conducted during its extended mission. Much like ocean waves that change their speed as they move, the new finding suggests there may be wave-like behavior deep inside Jupiter's metallic core that could power the observed magnetic field, study lead author Jeremy Bloxham of Harvard University told BBC Science Focus.

"These changes can be explained in large part by an eastward drift of the spot, but, as reported in this paper, that rate of drift is fluctuating."

Scientists previously knew this cluster of intense magnetic fields drift more than anywhere else on the gas planet, thanks to strong winds blowing right from its turbulent "surface" to 1,860 miles (3,000 kilometers) deep. At that deepest point, Jupiter's intense magnetic field is thought to dampen these winds.

The newfound jet may even be drifting at a miniscule scale of tens of centimeters per second in that area, as opposed to other jets on the surface which travel many times faster.

Still, the finding is a "very marginal measurement," said Kaspi, who was not involved with the paper. He says it's better thought of as an initial result within the noise threshold as scientists don't yet have enough data to conclude the jet fluctuates precisely every four years.

"If your data is just from five years, you can't really say anything about a four-year period."

More observations from Juno could deliver certainty soon, which would ultimately help scientists better understand the dynamo that powers Jupiter's complex magnetic field.