Judging purely from the liquidation and bankruptcy figures, there’s never been a better time to run a business than at the height of a global pandemic. Insolvency specialist John Fisk talked business editor Nikki Mandow through what might be going on.

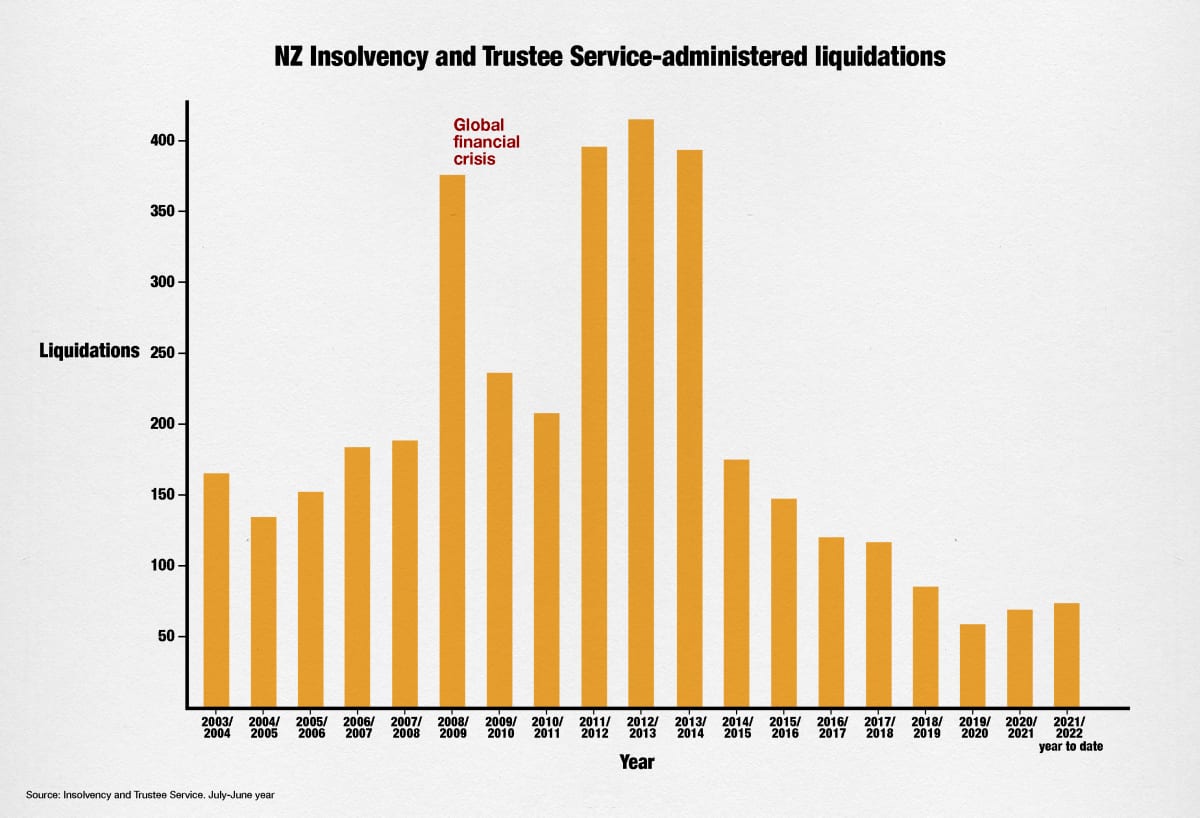

At first glance it makes no sense. Figures from the Government’s Insolvency and Trustee Service (ITS), also known as the Official Assignee’s Office, show ITS-administered liquidations for the more than two years of the Covid-19 pandemic are at the lowest levels in the almost 20 years for which figures are available.

As the graph shows, there were 69 ITS-administered liquidations in the July 2020-June 2021 year, the only full pandemic year covered by the figures, compared with 377 in the early stages of the Global Financial Crisis and 390-420 between 2011 and 2014, the year HSBC chief economist Paul Bloxham famously talked about New Zealand’s “rockstar economy”.

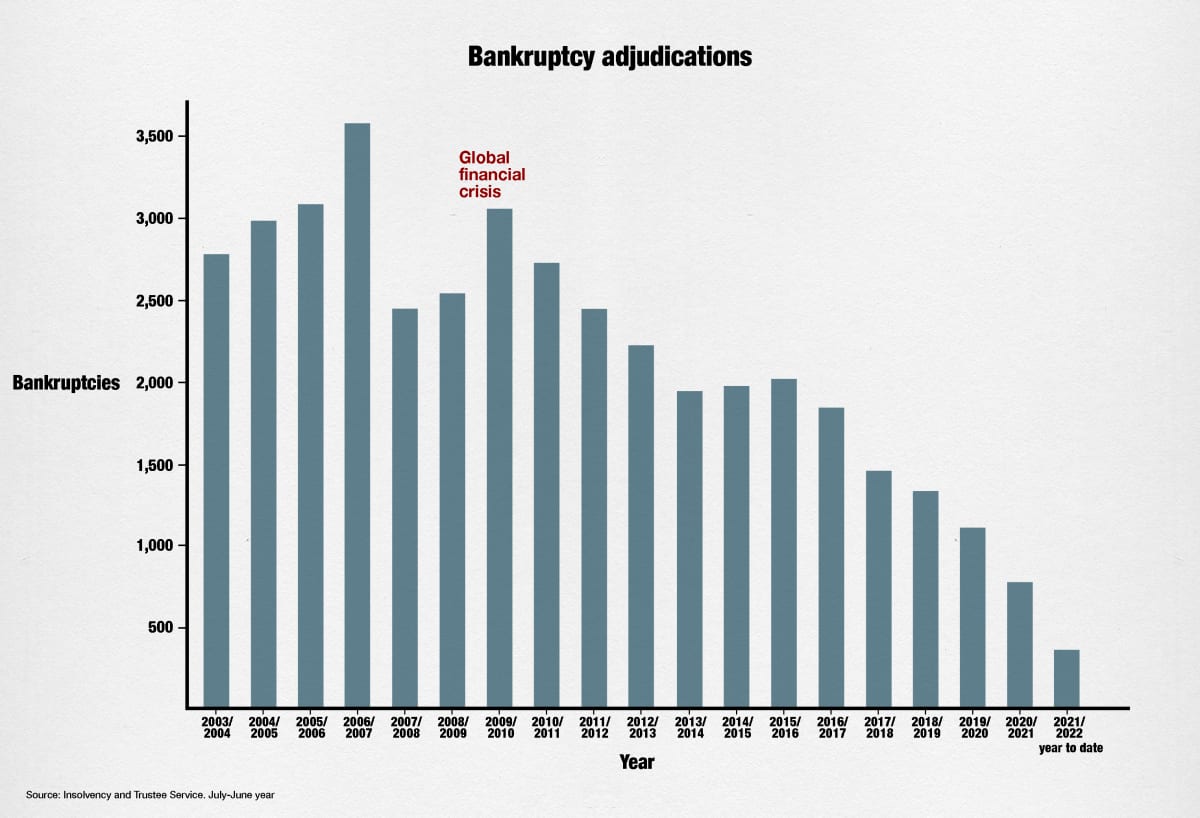

It’s a similar picture for bankruptcy adjudications - 346 in the year to date, 784 last year, 1107 in the 2019/2020 year.

That compares with 2500-3000 in the years before and during the GFC.

It’s the same through the developed world, says John Fisk, business restructuring services leader at accounting and consultancy firm PwC, and chair of RITANZ, the Restructuring, Insolvency and Turnaround Association of New Zealand.

“It’s been almost counterintuitive - when I tell people what I do, they say ‘You must be really busy.” Not so, or at least not with the liquidation and insolvency part of his business.

But actually, when you look at what’s been happening over the past two years, the figures aren’t so surprising, Fisk says. Quantitative easing, massive government support for businesses to maintain cashflow and employment, low interest rates, increasing asset prices, banks with healthy balance sheets, and a bigger bounce back from the initial impact of early lockdowns than economists were expecting; all have helped protect businesses from the economic shock of the pandemic.

Then there’s the IRD, which has been more lenient in its approach to collecting unpaid tax, and more willing to negotiate, Fisk says.

“It used to be quite difficult to get payment arrangements with Inland Revenue or get waivers of interest and penalties, but they are being more accommodating.”

The IRD’s 2021 annual report showed customers had set up approximately 140,000 arrangements to pay their tax in instalments, covering $3.7 billion in tax.

In fact, with the insolvency and bankruptcy numbers significantly lower than pre-Covid levels - levels which were already good because of the strong economy - it’s likely the combination of measures above has kept some companies afloat which would otherwise have gone under.

“There will be businesses which weren’t viable pre-Covid that took advantage of subsidies or leniency from landlords - effectively kicking the can down the road. At some stage they will need to look at insolvency because they are not viable.”

Some of these companies - or their creditors - will find themselves in a worse position than if they had gone under earlier.

“The longer they go on, the bigger the fail.”

What will happen next?

In the past, people looked back at the Global Financial Crisis to try to figure out how the economy would react in a downturn. That won’t work this time, Fisk says. “We are dealing with different ingredients - there is still a lot of demand, and there are supply chain problems - that was not the case with the GFC.

“We are almost in unknown territory in terms of how it will unfold.”

What everyone Fisk talks to agrees on, however, is there is more pain coming. Interest rates going up, inflation, supply chain problems, the end of the present long-running buoyant economic cycle, even the war in Ukraine are all adverse factors.

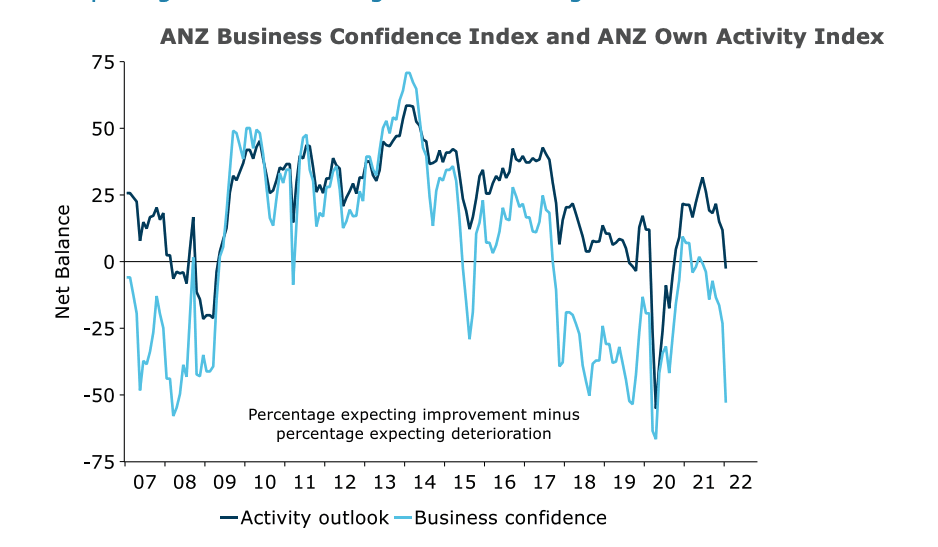

Meanwhile if house prices start falling, homeowners will start feeling less well off - and therefore less inclined to spend money. Already some of the consumer and business confidence surveys are looking bleak.

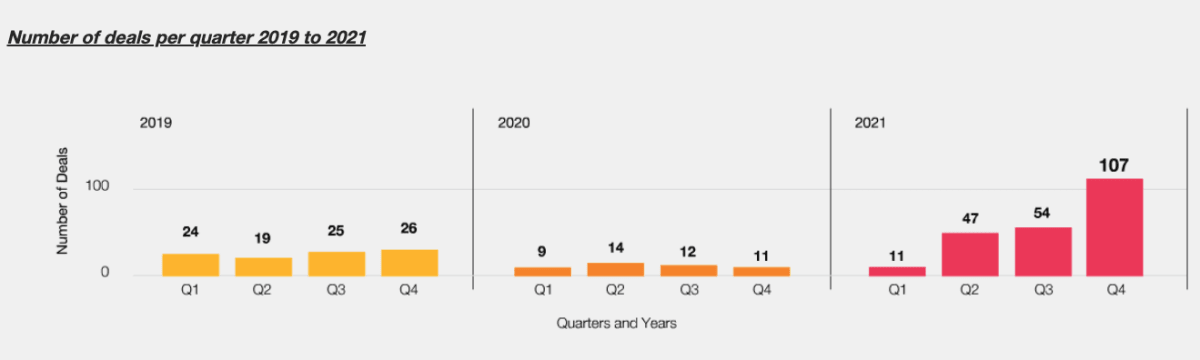

The low interest rates have also meant good sources of private equity funding available for companies in recent times, Fisk says. Investors have been looking for better returns than they are getting elsewhere.

The PwC mergers and acquisitions update for the fourth quarter 2021 showed record levels of deals activity, and having ready access to capital may have helped some companies stave off potential problems, Fisk says.

If that tide turns, combined with the other potentially negative economic factors, we could start seeing more companies getting into trouble.

But when and how remains to be seen.

“It’s been incredibly difficult to predict the timing and extent of these things. When we first went into lockdown we thought the world would end and there would be a massive spike in insolvencies, then we thought that would happen when government support came off. So I’d be loathe to put a time period on this or the extent of the damage which could be caused."

The working capital conundrum

Another thing Fisk and his colleagues are keeping a close eye on at the moment is the impact on businesses’ working capital of supply chain delays.

Take a kitchen installer. In pre-Covid times, a homeowner would put down a deposit for some trendy overseas-made appliances, the installer would order them, and a couple of months later they would arrive and go into the new kitchen.

These days, the appliances might take nine months to arrive, meaning the installer will likely be using that customer deposit to pay business operating expenses over a much longer period.

“So the customer is reliant on that kitchen company continuing to operate for all that time.”

If a sudden slowdown puts pressure on the installer’s business and they go under, there’s a risk the customer - and all the other customers with deposits on the installer’s books - loses their money.

There’s also a lot more working capital tied up holding a lot more stock than was the case pre-Covid, Fisk says.

Think builders stockpiling GIB board because they know it’s in tight supply and they want to make sure they’ve got enough for future jobs.

“We’ve gone from ‘just-in-time’ to ‘just-in-case’ inventory systems. That’s a lot of a company’s money tied up in holding assets that aren’t earning them anything until they sell them.

“With increasing interest rates, that’s an increasing cost on the business. If you can’t pass that on, that means reducing margins and potentially a less viable business.”