Stoicism may be having a renaissance. For centuries, the ancient philosophy that originated in Greece and spread across the Roman Empire was more or less treated as extinct – with the word “stoic” hanging on as shorthand for someone unemotional. But today, with the help of the internet, it’s gaining ground: One of the biggest online communities, The Daily Stoic, claims to have an email following of over 750,000 subscribers.

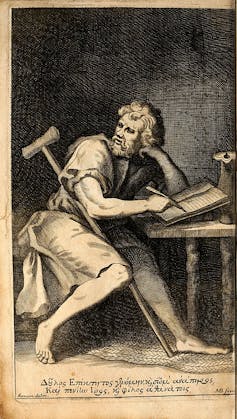

Perhaps it’s not so surprising. The United States’ current political climate has parallels to the last few centuries B.C. in ancient Rome, home of notable Stoics like the the philosopher Epictetus, a former slave, and the emperor Marcus Aurelius. During this period of instability, including the fall of the Roman Republic, Stoicism helped its practitioners find community, meaning and tranquility.

Today, too, society faces widespread feelings of isolation, depression and anxiety. Meanwhile, more and more people are looking for answers outside of mainstream religion. According to a 2022 Gallup Poll, 21% of Americans now say they have no religious affiliation.

Riding this resurgence of interest in Stoicism, I designed a college philosophy class that covers both theory and practice. When I ask students why they enrolled, I hear not only a genuine interest in the subject but also a desire to find meaning, purpose and personal development.

Core principles

Ancient Stoicism aimed to be a complete philosophy encompassing ethics, physics and logic. Yet most modern Stoics focus primarily on ethics, and they typically adopt four Stoic principles.

The first is that virtue is the only or highest good, including the cardinal virtues of wisdom, temperance, courage and justice. Everything apart from virtue – including wealth, health and reputation – might be nice to have, but they do not directly contribute to human flourishing.

Second, people ought to live in accordance with nature or reason. This principle reflects the Stoic belief that the universe exhibits a rational order, so we ought to align our beliefs and actions with eternal principles. Living in accordance with nature also reveals the interconnectedness of all things, showing how humans are part of a larger whole.

Third, a person can control only their own actions – not external events. Epictetus laid out this dichotomy in the opening sentence of The Enchiridion, a collection of his core teachings compiled by his student Arrian: “Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.”

The fourth principle is that thoughts about external events are often the source of discontentment or distress – a view that has influenced modern cognitive behavioral therapy. Again, this idea comes directly from Epictetus: “Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.”

Taken together, these principles form the bedrock of modern Stoicism, which aims to provide a coherent philosophy of life. Its hope is that once the practitioner accepts they are not entirely in control, they start building resilience and reducing anxiety. Not only is each individual the architect of their emotional life, but people can shape their own judgments in ways that are conducive to greater inner peace.

Stoicism in practice

In Discourses, Epictetus unequivocally states that study is not enough – in order to become virtuous, a person must couple study with practice. “In theory, there is nothing to restrain us from drawing the consequences of what we have been taught,” he noted, “whereas in life there are many things that pull us off course.”

In other words, philosophy is not only an intellectual endeavor but a practical and spiritual one: a way of life designed to move practitioners toward the Stoic conception of the good. Learning to cultivate core Stoic principles involves certain spiritual exercises.

My class incorporates a variety of these exercises so students can get a taste of Stoicism in practice. One is the “view from above,” which encourages the practitioner to imagine their life and certain situations from a bird’s-eye view, putting the insignificance of their current troubles in perspective.

Another is “negative visualization”: contemplating the absence of something we value. Instead of worrying about losing something, a person intentionally meditates on its absence, with the intention of fostering gratitude and contentment. When doing this exercise in class, students have imagined the loss of a possession, a scholarship or even a beloved pet.

A third exercise is journaling to plan and review one’s day. Reflecting on thoughts and actions allows a more objective, rational way to judge whether someone is living in accordance with their principles.

Once the exercises are incorporated with theory, Stoicism can become a type of spiritual project. As Epictetus wrote, “For just as wood is the material of the carpenter, and bronze that of the sculptor, the art of living has each individual’s own life as its material.”

The way of the prokopton

So what does it mean to be a practicing Stoic – a “prokopton,” in Greek?

For both ancient and modern practitioners, Stoicism is more than a set of abstract ideas. It is a set of guiding principles that permeate all aspects of one’s life. The goal is progress, not perfection – and exploring Stoic ideas alongside others is encouraged.

Today, there are at least three relatively robust Stoic communities online: The Daily Stoic, Modern Stoicism and the College of Stoic Philosophers.

By having dedicated communities, a guiding framework and distinctive spiritual exercises, parallels between Stoicism and many mainstream religions are undeniable. For moderns looking for such things, Stoicism may serve as a surrogate or complement to mainstream religion. People today tend to find the original Stoics’ notions about physics and theology implausible, but apart from those ideas, the core principles of modern Stoicism can be palatable to people who identify with contemporary faith traditions – or none.

The ancient Greeks believed that a philosophy of life is critical for human flourishing. Without a guiding ethos, they feared, individuals are likely to lead unstructured and unproductive lives, to pursue superficial pleasures and to feel that their lives lack purpose. Stoicism offered a path for some to follow – then, and now.

Sandra Woien does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.