Worldwide, greenhouse gas emissions are still increasing, and temperatures are rising across land and sea.

But what is climate change doing to Australia, the driest inhabited continent? The latest CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology report highlights that Australia’s climate is continuing to warm.

Extreme fire weather is increasing. Sea levels are rising. Marine heatwaves are becoming more intense and frequent. And oceans are getting more acidic. All of these come with serious consequences for Australia’s environment and communities.

Australia’s land is already 1.5°C hotter

On land, Australia has warmed by an average of 1.51°C since 1910. Our oceans have heated up by 1.08°C on average since 1900.

This doesn’t mean we’ve breached the Paris Agreement goal of holding climate change to 1.5°C or less, because this goal is based on the long-term average of both land and ocean temperatures. But Australia’s land and seas are now at record levels of heat.

Globally, 2023 was the hottest year on record – so far. But Australia’s warmest recorded year was 2019.

Why the difference? Between 2020 and early 2023, three consecutive La Niña events have kept Australia wetter and cooler than during most of the past decade, leading to fewer heat extremes than in 2019. Even so, these years were still warmer than most years before 2000.

As Australia keeps warming, extreme heat events will become more frequent and more extreme. Extreme heatwaves cause more deaths in Australia than any other natural hazard, peaking at 95 heat-related deaths in 2013-14, according to data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

More heat waves, longer fire seasons

Australia is notoriously fire prone. But fires differ hugely, from low-intensity grassfires through to enormous bushfires that consume forests. When extreme fire weather arrives – hot, dry and windy – small fires can turn large very quickly.

Extreme fire weather is more frequent and more intense than in previous decades. Hotter conditions dry out grass and leaf litter, producing more fuel for fire. This has led to larger and more frequent forest fires, especially in the southeast of Australia over the past 30 years. Dangerous fire weather will be more common in the future, and the fire seasons will continue to lengthen.

In extreme fire years such as the Black Summer of 2019-20, when large areas of Australia’s east coast burned, carbon dioxide emissions from bushfires and prescribed burns can actually outweigh Australia’s total emissions that year. However, these emissions are offset in large part when trees and shrubs regrow.

Drier in the south, wetter in the north

Climate change is driving a major divergence in where rain falls in Australia.

In northern Australia, average wet-season rainfall is now about 20% higher than 30 years ago.

But in southwestern Australia, rainfall in the cooler, growing-season months has declined 16%, and in the southeast by 9% in recent decades.

More rain in these regions now falls in heavy, short-lived rainfall events.

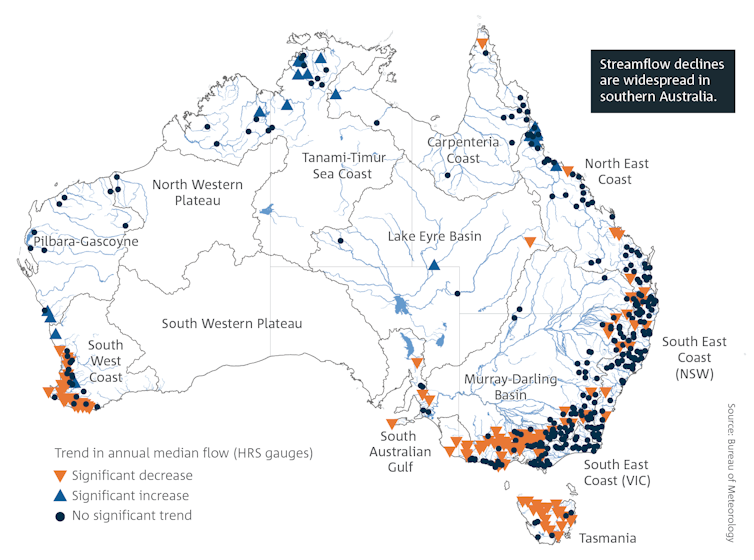

These changes are also reflected in our rivers, with significantly lower flows for about one third of the gauges in the south. Australia-wide, only 4% of our river gauges are measuring increased flows, and almost all of these are in the north.

Hotter oceans, rising seas

Almost all (90%) of the extra heat trapped by greenhouse gases has gone into the oceans. Oceans are getting rapidly hotter. This matters because ocean heat strongly influences weather patterns in Australia.

Australia’s oceans are warming faster than the global average. But the oceans off south-east Australia and the Tasman Sea are a particular hotspot and are now warming at twice the global average.

As the seas warm, they expand. This thermal expansion is one of the main contributors to rising sea levels. Around Australia, sea levels have risen 22 centimetres since 1900 – with half of that since 1970.

More emissions equals more heat

Avoiding the worst damage from climate change is conceptually simple and unequivocal: rapidly reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will help Australia meet its net zero 2050 target.

Tasmania’s northwest tip has some of the cleanest air in the world, which is why it was chosen to host the Kennaook/Cape Grim Baseline Air Pollution Station. For 48 years, this station has been recording concentrations of greenhouse gases. The picture it captures is stark.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentrations are now about 51% higher than pre-industrial levels, while concentrations of methane and nitrous oxide, both strong greenhouse gases, continue to increase. Their rate of atmospheric accumulation has rapidly increased in recent years even as some regions and some sources have begun to see emissions slow or even decline, such as reduced CO₂ emissions from land clearing, globally and in Australia.

Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuel use have been increasing since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and increased by 1.1% from 2022 to 2023, reaching the highest annual level ever recorded.

Australia’s carbon contribution

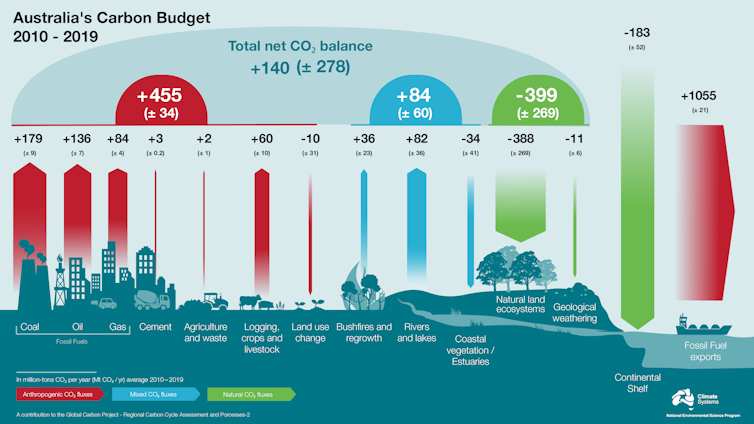

This year, the State of the Climate report for the first time quantifies Australia’s major human and natural carbon sources and sinks and how they contribute to global CO₂ levels.

It shows the average annual carbon content embedded in Australia’s fossil fuel exports between 2010 and 2019 (1,055 megatonnes) was more than double the average annual national carbon emissions over the same period (455 Mt). However, the emissions of these carbon exports are accounted in the countries where the fossil fuels are used.

It also demonstrates the importance of maintaining the integrity of our natural land ecosystems. Ecosystems are Australia’s most important carbon sinks, but their effectiveness as sinks depends on factors including the future evolution of the climate and how it will affect rainfall and wildfire regimes.

What lies ahead for Australia?

Australia’s warming is expected to continue, which will lead to more extreme heat events, lower rainfall in some regions, and longer droughts.

We can expect to see more intense rainfall events, even in regions where average rainfall falls or stays the same.

Sudden intense rains make flooding more likely, especially in urban areas where concrete and tarmac prevent the ground from soaking up excess water and in low-lying coastal areas where rising sea levels amplify damage from other climate hazards.

Climate change is already here. Through multiple lines of data and evidence, we have tracked what it is doing to make Australia hotter, more prone to floods and fires, and cutting river flows in the south where most of us live.

If warming continues, these trends will get worse over time. Understanding these changes and the impacts to Australia will help manage climate risk, now and in the decades to come.

Blair Trewin, Senior Research Scientist at the Bureau of Meteorology, contributed to this article

Correction: This article originally gave an incorrect figure for heat-related deaths. It has been amended.

Pep Canadell receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program - Climate Systems Hub

Neil Sims does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.