Our cultural touchstones series looks at books that have made an impact.

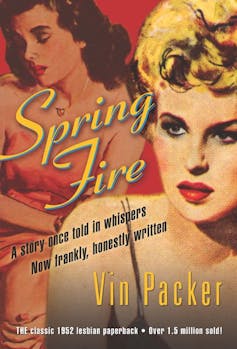

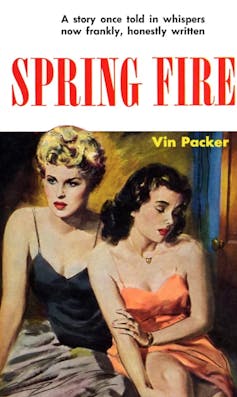

In 1952, Marijane Meaker, under the pseudonym Vin Packer, had the first pulp fiction hit with a purely lesbian plot.

Spring Fire, which sold 1.5 million copies in its first print run, is set at the fictitious Cranston University, in an unnamed Midwest town. The life it depicts – of sororities, fraternities and frowned-upon independents – is one in which hormones rage and social conformity rules. Enter the lesbian …

The book’s cover reads:

A story once told in whispers

Now frankly, honestly written

Burning to tell

Meaker worked as an editorial assistant at Gold Medal Books, a paperback publisher launched in 1950. Its novels “were intended as reliable, disposable entertainments: fast, short, and full of action”.

She was recruited by Gold Medal editor-in-chief, Dick Carroll, to write Spring Fire, her first book. “What kind of story is a young girl like you burning to tell?” Carroll asked. Meaker replied that she wanted to write about boarding schools. She had wanted to attend one because

I had heard homosexuality ran rampant in places like that. I wanted to find out if my suspicions were right, that I was one of those. Sure enough, I was rewarded with first love.

Carroll gave her clear parameters:

The girls would have to be in college, not boarding school. And, you cannot make homosexuality attractive. No happy ending.

Publishers had first been alerted to the possibilities of books with lesbian-themed plots a couple of years earlier, with Women’s Barracks (1950), an autobiographical novel with lesbian content, set among female Free French soldiers in a London barracks during World War II. Ruled obscene and banned by a Canadian court, it went on to sell in the millions.

Meaker, who died late last year at the age of 95, would go on to write in a range of genres, under several pseudonyms – including 19 more books as Vin Packer, though only two of these would deal with homosexuality.

As Ann Aldrich, Meaker wrote non-fiction accounts of lesbian life in Greenwich village. She wrote fiction for young children as Mary James, and she was an award-winning author of young adult novels under the name M.E. Kerr. In 1993, she won an award from the Young Adult Library Services Association for being “a pioneer in realistic fiction for teenagers”, with books like Dinky Hocker Shoots Smack (1972) and I Stay Near You (1985).

Read more: Friday essay: the complex, contradictory pleasures of pulp fiction

Queer New York life, with Patricia Highsmith

Under her own name, Meaker wrote a memoir of her two-year romantic relationship with the now more-famous Patricia Highsmith, who she met in a “word-of-mouth” only lesbian bar, L’s, in Greenwich Village.

Highsmith, best known for her Ripley novels, wrote one lesbian novel, The Price of Salt, under a pseudonym (Claire Morgan), also published in 1952. The award-winning film version – Carol – was released in 2015, starring Cate Blanchett.

Meaker’s memoir, published after Highsmith’s death, gives a glimpse into queer life in 1950s New York. Together with their gay and lesbian friends, Meaker and Highsmith negotiated the known safe spaces for queer people – some of them fully in the closet, others more or less out, though all suffered societal and familial constraints of some kind.

They knew, for instance, where they could eat where women in pants would be welcomed, and which lesbian bars had not been taken over by the mafia. The memoir also tells of two very different literary reputations still in the making. Highsmith, published in hardback by literary publishers, at that stage earned far less (and had far fewer readers) than Meaker, whose work appeared in paperback, reaching millions because of its accessibility.

“I loved her writing,” Meaker told Terry Gross in a 2003 NPR interview about the memoir. “I think we shared a common theme, which was folie a deux, a sort of simultaneous insanity, two people involved with each other very closely, often in a crime.”

As writers, they lived an isolated life in an old farmhouse outside of New Hope, Pennsylvania, where both had strict writing routines. Different social needs and Pat’s excessive drinking were among the things that drove them apart – though as Meaker writes, they had ‘“such good horizontal rapport” that they dragged out their separation, reconciling more than once just as the movers arrived to take Highsmith’s belongings away.

Read more: Friday essay: hidden in plain sight — Australian queer men and women before gay liberation

Lesbian pulp fiction and unhappy endings

Since the 1890s, the production of “pulp paper” – quick to produce and still acidic (giving it a shorter life) – revolutionised publishing. It enabled the production of cheap genre fiction and magazines that anyone, including the working classes and young readers, could afford.

Pulp fiction did not appear in hardcover and was designed to be read quickly. As Ann Bannon, another writer enlisted by Meaker to write lesbian pulp noted, “You could read them on the bus and leave them on the seat.”

Censorship had to be avoided. As many of the novels would be distributed through the post, nothing could raise the ire of the postal service censors, who could then scuttle the whole book shipment.

Meaker realised: “my heroine has to decide she’s not really queer.” Her publisher responded, “That’s it. And the one she’s involved with is sick or crazy.” It set the tone for the denouement of much lesbian pulp fiction to come for at least the next decade.

When asked how she felt about writing such hopeless endings, Meaker said:

I laughed. I was not politically conscious to that point. It really hadn’t begun yet. I wrote this, I think it was '51 or '52. I was right out of college. And I thought it was a funny idea. You don’t have any – when you’re writing these things, you don’t have any vision of the future […] It was – I was delighted to get my first book published. And if that was the rule, well, I was willing to follow it.

So the lesbian pulp fiction genre began. While the required unhappy ending may not have bothered the many male readers attracted to titillating covers and admittedly vague descriptions of female same-sex activity, for those women and girls reading to see possibilities for their own desires and lives, these plots offered seemingly slim pickings.

Yet given the almost complete lack of lesbian representation in popular culture, to even hint at its possibility was transformative for many. Lesbian fiction author Katherine V. Forrest describes her own first encounter with lesbian pulp at the age of 18:

Overwhelming need led me to walk a gauntlet of fear up to the cash register. Fear so intense that I remember nothing more, only that I stumbled out of the store in possession of what I knew I must have, a book as necessary to me as air.

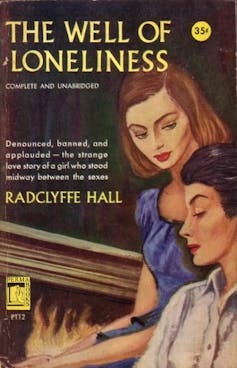

Censorship had been a factor in earlier hardback novels addressing lesbian topics. Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928) had been the subject of an obscenity trial, keeping it out of print in Britain for 20 years.

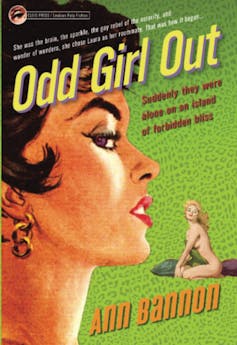

In many ways, when its hero/ine Stephen Gordon gives up their lover Mary to heterosexual marriage, the novel foreshadows the later pulp lesbian protagonists who lose out to male rivals, mental illness, or death. But not all lesbian pulp ended badly. Perhaps the most enduring of lesbian pulp writers, Ann Bannon (pseudonym of Ann Weldy), managed to depict lesbian lovers who survived beyond the ending.

This was in part made possible by the relaxation of obscenity laws later in the 50s, following the trial of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Bannon’s characters frequented the secret lesbian bars and clubs of New York City of the 50s and 60s, and led lives based on people Bannon actually knew.

Read more: Queer identity, lust and grief in Lauren John Joseph’s debut novel

Spring Fire confirmed readers’ desires

Spring Fire offers the pleasures of female same-sex activity, while ostensibly shutting down the possibility of lesbian life and love. The central character, sorority sister Susan Mitchell – Mitch – could be read as a 50s butch lesbian in the making, rather than a young woman seduced by a disturbed and scheming femme fatale.

She has a history of crushes on and obsessions with girls and women. Her masculine nickname confirms this identity, as does the moment she catches herself in the mirror, when “the wetness of her hair gave it a bobbed look, and the reflection was like that of a young boy”.

She also, apparently instinctively, knows what to do sexually when she takes the lead with her lover Leda and is empowered by the experience of dominance:

A feeling of power, and the knowledge of Leda’s quivering submission, filled Mitch as she let her eyes stare up at the blackness in the cellar. When she had gone to Leda, she had not known what she would do, and it happened without thought or care for what followed, but it was easy and natural. She was the conqueror, and it was a sensation abundant in glory and desire.

This is no naive innocent who can brush off such experiences, though at the end of the novel she is apparently cured by her sessions with a sympathetic doctor: “She had a clean feeling that was there whenever she finished talking with Dr. Peters, and she knew she was whole now.”

This was enough to satisfy the censors: Leda, the original seductress, has a “complete nervous breakdown” and is sent to an asylum, taking both aberration and condemnation with her. Mitch is free to return to heterosexuality and normality.

The ending is forced, and cannot account for what has gone before, but it serves to shut down the possibility that lesbian love and life might be possible or desirable. Nevertheless, countless women read Spring Fire as confirmation of their own desires, taking it into over 15 printings.

Read more: Fifty shades of erotica: how sex in literature went mainstream

Speaking in a double voice

Lesbian pulp speaks in a double voice. Same-sex attracted women could see their own desires reflected, while the plot’s ultimate condemnation of lesbianism satisfied the censors and those concerned with public morality.

For readers now, the on-campus same-sex activity pales in comparison with the compulsory heterosexuality that expresses itself in continual coercion, and in date rape early in the book. Such things did not contravene censorship standards the way a happy lesbian would.

But this was before the existence of publishing houses specialising in queer literature – and before its public recognition in awards such as the Lambdas. Legally recognised same-sex marriage had barely been imagined.

Despite the ending, for many of its first readers, Mitch’s thoughts in Spring Fire were a chink of light, illuminating a world in which this forbidden love was real:

Until Leda, there had been no one who had set her whole body pulsing with the sweet pain and the glory in the end.

Mandy Treagus receives funding from the Australia Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.