After Lyn Hughes took a walking tour of Chicago’s Pullman neighborhood in 1990, she decided to create a museum around its critical connection to the Black labor movement. At the time, she didn’t know much about the museum business. But she saw a need.

“I just thought that there ought to be some place in Pullman that talked about the African American experience, and I was appalled that nobody was doing that,” Hughes said.

Five years later, Hughes founded the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum in a humble brick house. That would be just the beginning of a long battle to bring more recognition to the Black men who were the masters of hospitality on America’s most luxurious railroad cars in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Federal efforts to designate Pullman as a national monument took off during the Obama administration, but the spotlight was trained on the southern end of the neighborhood, founder George Pullman and the railroad car factory. Hughes’ museum about porters was sometimes overlooked.

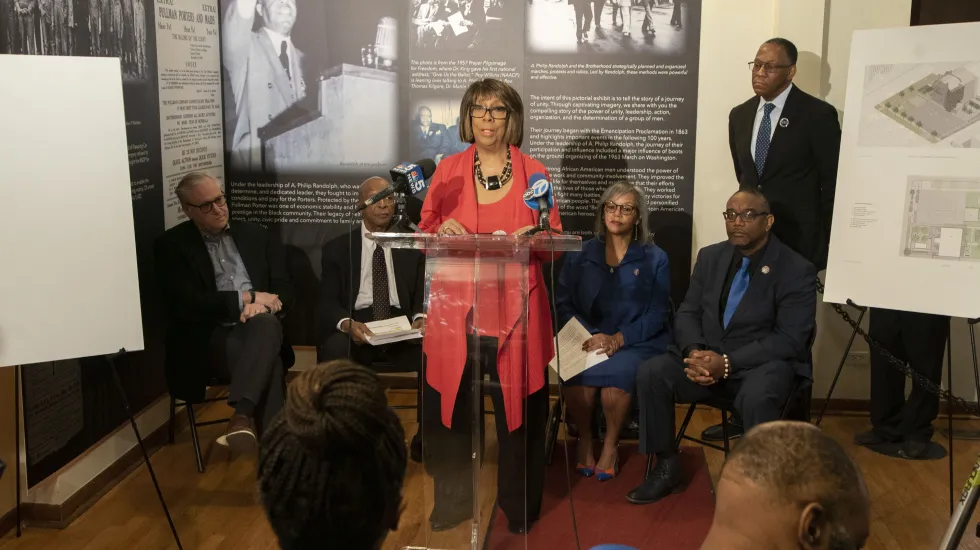

Now, Hughes and other museum leaders aim to change that, announcing plans last month to expand while creating a new cultural district that would draw tourists and boost local employment.

For Hughes, the whole story began when she chanced upon that walking tour of Pullman, a Far South Side neighborhood that started in 1881 as one of America’s most prominent company towns — a residential district for the workers who made railroad cars at Pullman’s factory.

In 1990, Hughes had recently moved to Chicago from her native Cincinnati and was looking for buildings to purchase. The 77-year-old, who holds a Ph.D. in education with a minor in museum studies from Northern Illinois University, had previously worked in real estate.

Someone had told her Pullman’s north end was a good place to find buildings that could be rehabbed and resold. She stopped inside one of the area’s most majestic old buildings, the former Hotel Florence, for lunch. She overheard some people at the next table talking about a walking tour and decided to sign up.

Hughes said she was the only African American on that walk, where she was fascinated to learn about Pullman’s distinctive architecture and its history — stories such as the 1894 strike by the factory’s white workers, who included many immigrants from Europe. The strike paralyzed rail traffic and prompted clashes with federal troops in one of the country’s biggest and most tumultuous labor battles.

But as that walking tour ended, Hughes asked, “Can you tell me what role African Americans played in the Pullman story?” According to Hughes, the tour guide had little to say. “He responded by saying, ‘Well, I think they worked on the trains,’” she recalled.

Determined to learn more, Hughes went to a Chicago Public Library branch and checked out “A Long Hard Journey: The Story of the Pullman Porter,” a 1989 book for young adults by Patricia and Fredrick McKissack.

“I found myself weeping out loud,” Hughes said. “It touched me in a way that changed the trajectory of my life. Why didn’t he [the tour guide] share that information?”

Seed money from a divorce settlement

Hughes started making plans for a museum showcasing Pullman porters — thousands of African American men who worked in Pullman sleeping cars. Pullman’s company manufactured these luxurious coaches at his local factory while operating those cars on various railroads across the country.

“The Pullman porters started working for the Pullman Company right out of slavery because he recruited them,” Hughes said. “He wanted to hire people who were skilled in hospitality. And so, he recruited former slaves who worked in the houses on the plantations.”

The porters were considered at the bottom of the hierarchy of trained railroad employees. But because of their skill in hospitality service, their labor made Pullman, who was white, “a very rich man,” she said.

After gathering photographs with help from the Chicago Historical Society and other institutions, Hughes opened her museum at 10406 S. Maryland Ave. — one of three buildings she had purchased and rehabbed in North Pullman.

“I did not pay more than $10,000 for each building,” said Hughes. “There was so much blight and vacant lots. It was just terrible.” But she saw the neighborhood’s potential.

“I started the museum with my divorce settlement, which was $240,000,” Hughes said. “That’s a shoestring budget to create a museum. I got $188,000 from the state of Illinois after I started the work. I never depended on grants.”

“Dr. Hughes really does not get the credit that she deserves,” said David Peterson Jr., the museum’s president and executive director. “She’s a trailblazer for carving out this story and helping teach it to the next generation.”

“You’re not gonna find a stronger advocate for African American history than Dr. Hughes,” said David Doig, president of the Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives nonprofit, which has played a leading role in developing Pullman. “She’s just a tenacious fighter.”

Hughes named the museum after A. Philip Randolph, the African American labor activist who organized Pullman porters, forming the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925. When the porters won a contract from the Pullman Company in 1937, it was the first major labor deal between a corporation and a union led by African Americans.

“I have had the honor of meeting thousands of their descendants and many, many, many men who were porters,” Hughes said. “They were gentlemen. The job was one of the best jobs that a Black man could have during that time.”

The porters changed the direction of the African American population across the country, Hughes said, because they moved on the trains nationally.

“They are responsible for the foundation of the Black middle class,” she said. “In Chicago, they were the ones who owned the greystones in Bronzeville. They were the ones who had businesses. Their children went to college.”

The old Pullman factory shut down in 1981 after decades of decline, and it would not be designated a national monument until 2015, when President Barack Obama made a grand announcement, noting his wife is a great-granddaughter of a Pullman porter.

That legacy, he said, made it possible for her to attend college and law school. “Without this place, Michelle wouldn’t be where she was,” he said.

But Obama’s declaration didn’t mention the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum. “It was like we didn’t exist,” Hughes said. “That broke my heart.”

Connecting two sides of historic Pullman

Hughes said Pullman’s designation as a national monument brought new attention to the museum, despite her disappointment that her museum had been overlooked.

“We have so many people who have visited us since it became a part of the National Park Service,” she said.

Meanwhile, the National Park Service officials have done more to recognize the porter museum. Teri Gage, superintendent of the Pullman National Monument, recently called it an “extremely important partner.”

In the past, the porter museum — which closed during the pandemic and will not reopen until 2023 — relied on $5 admission fees and the efforts of a completely volunteer staff, and it was open only three days per week.

Now, the museum has a goal of raising $30 million to fund an expansion — plus plans for a “Pullman Porters’ Row” of shops and restaurants.

Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives, which rehabs homes in North Pullman and sells them as affordable housing, is donating the building just south of the museum.

“It’ll double their footprint and give them more exhibit space, more event space, classroom space, office space, all that kind of stuff,” Doig said. “We want to see this happen.”

The museum plans to add the Jesse White Labor Research Library (named after the soon-to-retired Illinois secretary of state) and the Dr. Lyn Hughes Ladies Auxiliary Women’s History Museum. She intends that effort to call attention to yet another overlooked group: the wives and other family members of porters.

“They made it possible for the men to do what they did,” Hughes said. The women held meetings under the guise of a tea or a bake sale, but they were actually organizing the porters union, using the proxy power they’d been given by their husbands. “When the Pullman Company would call those men in and say, ‘We heard that you were at a meeting and you voted to form a union,’ they said, ‘No, my timecard here shows I was at work.’”

Peterson said the new businesses around the museum will employ local residents and offer job training. The hope is to give an economic boost to Pullman’s north end, an African American neighborhood that has more poverty than Pullman’s more racially diverse southern portion, where tourism is concentrated.

“What we’re about to do on the north end is going to make everybody proud,” Hughes said.

Robert Loerzel is a freelance writer. He wrote this story for WBEZ.