It's not every day somebody looks at a lump of cheese and thinks it could help solve part of the mounting problem that is e-waste. But that's pretty much what researchers in Switzerland have done by creating a sponge-like material from whey proteins, a material that can suck up the milligrams of gold used in millions of electronic devices.

News of the work was reported by ETH Zurich (via Sweclockers), the institute that carried out the research in question. If you take a look inside any gaming PC, especially a fully kitted out desktop, you'll see lots of large electronic circuit boards and many of the interconnects within it contain gold and other valuable metals.

Extracting these from old boards isn't easy, though, which is why there's this kind of research going on.

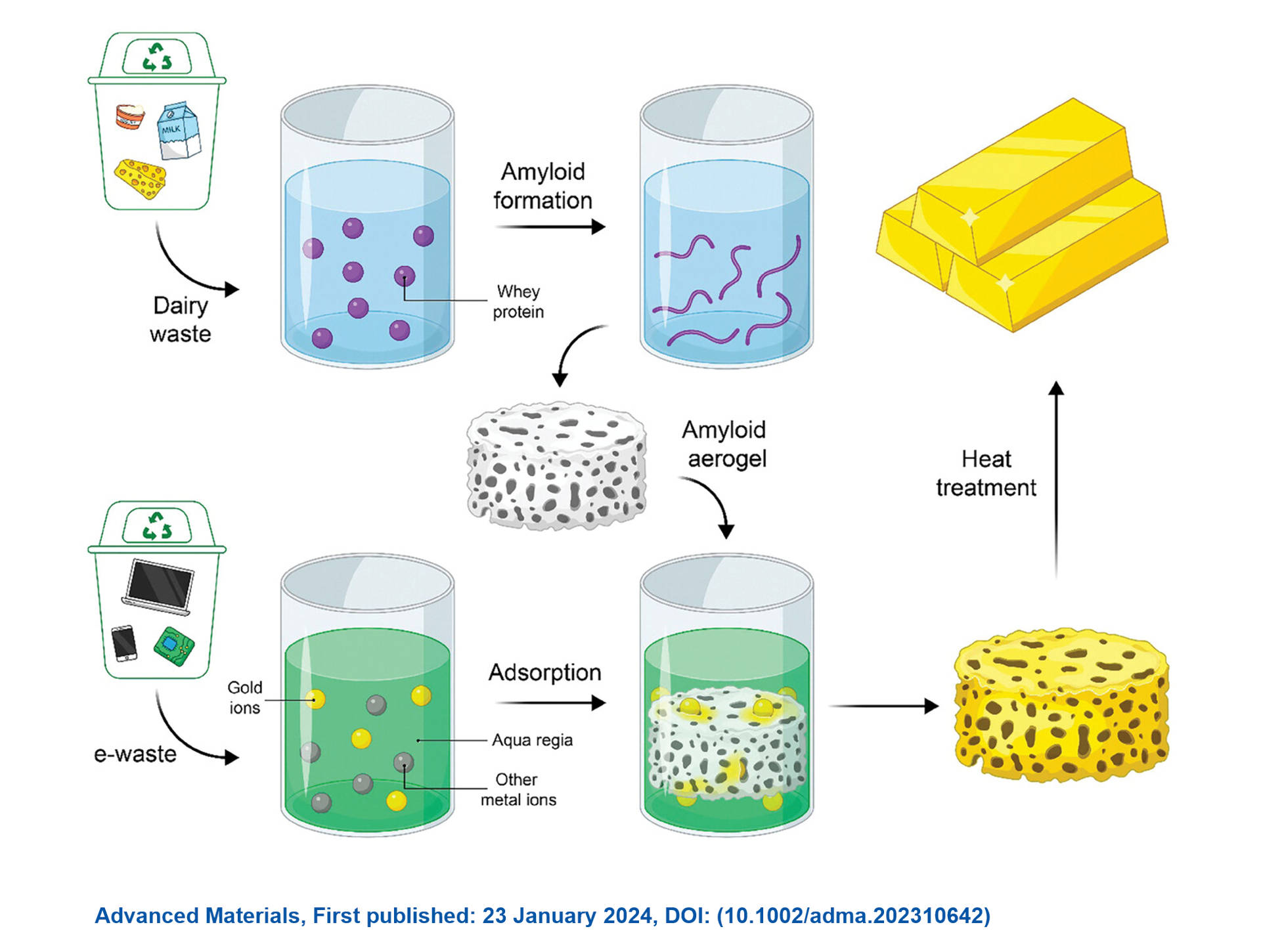

Normally, to get hold of the rare metals, the e-waste is put into a large acid bath, which dissolves the materials into a solution. Floating around in that liquid are gold ions but how to get hold of them? Enter stage left, whey.

This is the liquid that you see when milk goes off, rising to the top as the solid curds fall. It's also a by-product of the cheese industry and since it comprises lots of nice proteins, it has multiple uses, such as food or health supplements. The team of researchers wasn't interested in bulking up, though.

What they did was take the whey proteins and use them to form fibrillar amyloids; think of these as being groups of proteins in long, thin tendrils. They knit together and once dried, take the form of a sponge, which is then placed into the acid solution containing the gold ions. Once it's absorbed as much as it can, the sponge is removed and then heated, to make a gold nugget.

Best gaming motherboard: the best boards around

Best AMD motherboard: your new Ryzen's new home

The ETH Zurich report says that 20 motherboards were used to test the method and together they yielded a total of 450 milligrams of gold, worth around $30/£25, depending on the market. It's not 100% pure gold, as the sponge does absorb other metals, but they were in sufficiently small quantities to rate the nugget at 22 carats.

And best of all, this method isn't just a laboratory exercise: It's genuinely cost-effective according to the researchers, as the combined cost of the materials and energy required is 50 times less than the value of gold recovered. That means it has a far greater chance of being properly commercialised and scaled to the size required to tackle the vast amount of e-waste generated each year.

Cheese: Is there nothing it can't do?