Spark shines a light on a group of young people making moves in tech to tackle digital inequities | Content Partnership

When Aotea College adopted a ‘bring-your-own-device’ learning approach a few years ago, something changed among the student body.

The largest state secondary school in Porirua has a diverse array of students and a moderate decile of five, meaning they come from a range of income backgrounds.

But once students were expected to bring their own device from home to access parts of the learning process, a once even playing field was shaken up and cracks began to show.

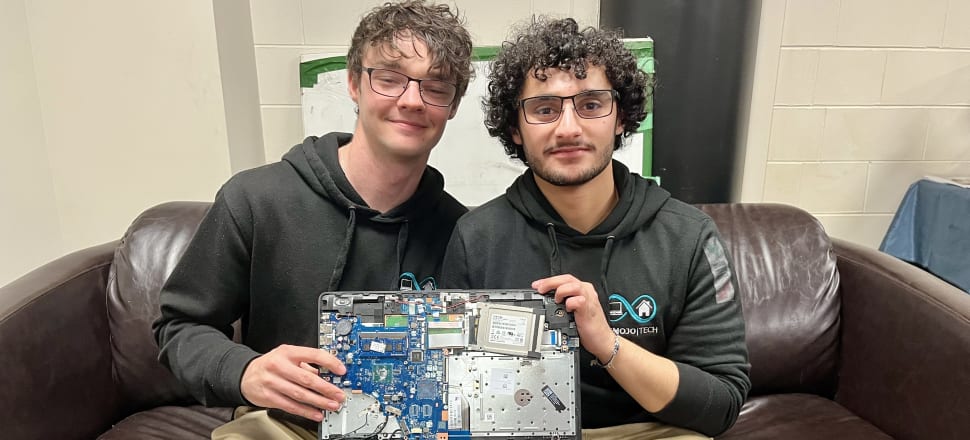

Aotea alumni Hadi Daoud and Owyn Aitken saw the difference it made first-hand.

“I would say for a lot of the students at Aotea who didn’t have access to a device, one interesting thing that you wouldn’t expect is a lot of them had no interest in getting a laptop,” Aitken said.

He reasoned that not having grown up with access to a device may have coloured his classmates’ desire to use one. On top of that there’s the stigma and whakamā around not having the digital literacy of your peers.

Then another seismic shift occurred when Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced a nationwide lockdown in March of 2020.

Hadi remembers a clamouring from the school’s senior leadership team to try and get devices together for students who may soon have to access virtual classrooms from homes where multiple kids have to share a family computer, or there is no internet access at all.

It was a crucial moment for him and Aitken. As self-described tech nerds, they’d been running tech refurbishment workshops at the school for years, salvaging parts from old and broken laptops.

They started working with the school to get devices to students in need. Daoud said it was something of a moment of clarity when it came to properly seeing the issue of digital inequity.

“That was the exact point when it was clear and the light was shone onto the issue of digital inclusion,” he said.

It’s one of the many ways the digital divide manifests, with inequitable access across society to technologies steadily becoming more and more foundational to modern life.

One in five New Zealanders experiences digital exclusion in some way*, and it’s estimated that around 175,000 households in New Zealand still don’t have access to the internet.

It’s also the reason Daoud and Aitken found themselves telling their story to around 1,500 Spark employees the other week at Spark Arena in downtown Auckland, and zooming in from satellite sites around the country, along with a line-up of young people who have found an innovative way to help bridge that gap.

Daoud and Aitken’s refurbishment programme, Remojo Tech enables sustainable accessibility through education and connecting communities with equitable resources.

Remojo Tech has also partnered with Spark Foundation and Digital Future Aotearoa to establish Recycle a Device or RAD, an initiative that sends Remojo Tech trainers around the country to teach the basics of computer refurbishment to high school students and community groups to increase digital skills and access to technology, while saving old gadgets from sitting in landfill.

Devices that are donated and refurbished through RAD are then distributed to households in need. The programme has already diverted nearly three tonnes of e-waste since the programme begun.

Sharing the stage with them were the prodigies behind an affordable water-quality testing kit, an online platform for sharing the correct pronunciation and stories underlying Pasifika and Māori names, and a petition to mandate correct captioning on New Zealand media.

Spark goes ‘all-in'

Spark employees stopped what they were doing on Tuesday week before last and showed up either virtually or in-person to the Spark Arena in downtown Auckland to put their heads together on the issue of how to bridge the digital divide.

Outsiders may have gleaned what was going on from the email auto-reply adopted by employees saying why they were electronically out of reach for the day, just like the million New Zealanders who face some kind of digital access issue.

“It can be easy to forget just how much we rely on technology to go about our everyday lives,” the email read. “It’s an essential tool to participate effectively in society – whether it be at school, work, applying for a job, paying the bills, streaming TV or music, checking the bus timetable, booking an Uber, or even as simple as getting in touch – like you did with me today.”

Around 1500 Spark employees participated in an afternoon of workshops where they brainstormed ways to combat the issue, which CEO Jolie Hodson said was only going to become more impactful in years to come.

“Since the arrival of Covid on our shores we have seen a huge acceleration of digitalisation,” she said. “But we’re also facing another big, global challenge that will drive digitisation as well – and that is climate change. New Zealand businesses are going to have to rapidly decarbonise over the coming years, which means the accelerated pace of digitisation we have seen since Covid hit will continue as Aotearoa transitions to a low-carbon economy.”

She said system-wide change, investment, and better coordination across the public, private and community sectors would be needed to stop people in that ‘one in five’ getting left behind, but that Spark could make change now by considering digital equity in all aspects of its business – from the products it creates and services it provides, to the networks it builds and where they’re built, the technology it develops, the workforce it creates and the way it manages data, privacy, security and AI.

Spark noticed the skyrocketing need during the rapid shift to virtual life in the first years of the pandemic.

Since the company’s not-for-profit, low-cost broadband initiative Skinny Jump first launched in 2016, it has seen a 360 percent increase in connections, providing subsidised internet to households who find that cost is a barrier to having an internet connection at home – such as beneficiaries, disabled people, the elderly, people living in social housing, jobseekers, people recently released from prison, and new refugees.

Skinny Jump lead Martin La’a compared digital equity to travelling down a river in a waka. Different people start at different points along the river or its tributaries, and face different challenges as they move along.

Instead of rapids or waka leaks, it’s affordability of technology, likelihood of learning digital skills, language barriers, accessibility and different levels of confidence that leave New Zealanders floating along at sometimes very different speeds.

There are 150,000 New Zealanders with a vision impairment for whom the screens most of the country stares at for hours a day may not be useable.

Then there’s the 115,000 adults without proficient English.

Spark Foundation lead Kate Thomas said product and service design are often made for the “masses in the middle”.

“Covid shone a spotlight on digital equity,” she said. “We’ve started to see more and more community groups leaning into this space.”

The Digital Inclusion Alliance Aotearoa was established in 2018 with the aim of bringing those groups together in collaboration. The Alliance is Spark’s community partner on Skinny Jump, managing a network of over 300 community organisations, including 176 public libraries, who assess eligibility for the service and sign customers up.

“The people we aim to support are those who are the most digitally disadvantaged and the one thing they really appreciate is help from someone they trust,” said Laurence Zwimpfer, director of operations for the Alliance.

The digitally overlooked

But while getting internet into more Kiwi homes is one way to combat the digital divide, so many different causes of the problem means a fix has to come from many different angles at once.

Hodson said it’s a “multi-dimensional problem” in need of a “multi-dimensional solution”.

The line-up of young people who followed her onto the stage were there to inspire some multi-dimensional thinking.

To’e Lokeni and Mannfred Sofara from Bishop Viard College in Porirua faced digital inequity and put an idea to tackle it into action.

Lokeni told the crowd that after years of having his name mispronounced at school, he eventually decided he wanted to do something about it.

“Identities were eroded by every teacher or person of influence who mispronounced a name,” he said. “Correct pronunciation sends a message that a person matters.”

He said it was not uncommon for young people in his position to go by a different name in order to avoid the awkward minimising experience of the teacher calling the roll.

Lokeni and Sofara started out developing their digital platform Fa’amalosi - Say It Right on a teacher’s laptop, and then from devices they were able to borrow.

Pushing against the stereotype they heard that ‘Pasifika don’t do tech’, the students built a website and a marketing plan that makes correct pronunciation available for Māori and Pacific names.

“Mispronunciation excludes the narratives behind a name,” Lokeni said. “This is a solution that could lead to a more equitable distribution of power.”

Life like a muted Zoom meeting

Hope Cotton from St Oran’s College in Upper Hutt says she has lived her whole life with her mic off.

As one of the 880,000 people in New Zealand who are deaf or hard of hearing, she had to badger her teachers through the pandemic to make sure there were accurate and comprehensive captions for online learning.

Unlike countries such as Australia, the UK and the US, closed captioning is not required for media in New Zealand.

Cotton, who is also the youngest member of the New Zealand Foundation for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, is spearheading a petition calling on the Government to institute legal captioning requirements.

She said this would fulfil the broken promises of New Zealand signing the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities back in 2008.

The petition has almost doubled in signatures since she spoke at the event, going from just under 900 to almost 1600 a week later.

Cotton shared the barriers to a regular life she deals with every day that the hearing population seldom has to cope with.

“Imagine always being on a muted Zoom meeting,” she said. “Or during family movie nights, when I often have to sit by myself and read a book. We are more disabled by a world that doesn’t include us than by our bodies.”

But increased awareness of the issue and the rising count of signatures have given her cause to be optimistic looking forward.

“It gives me hope,” she said. “It means one day there might be a deaf prime minister or CEO.”

A science lab in a shipping container

Up next to talk about her own experience grappling with digital inequities was Rangipo Taukira-Mita, who wanted to create a way to keep track of the health of her local river without access to fancy science equipment or a laboratory.

Along with her classmates, she developed a technology-backed water-testing programme which uses data from water-testing kits, motion capture cameras and weather stations to make it affordable to keep track of the quality of New Zealand’s rivers.

She was inspired to get into it after noticing the river by her South Auckland school was in a state.

“How can we stand strongly and pepeha if our mountain doesn’t exist anymore and the river we swim in is polluted,” she said.

She and her team had to start out sending water samples to Auckland University of Technology before they could build the water kit, due to the limited resources of her school.

“Most of the magic happened in a shipping container,” she said. “We started with no money - we were pretty much running off koha.”

Her collective, Te Pu-a-Nga Maara, has now expanded to reach marae all across the country, and has even sent kits out to Tonga and Italy.

Along with tech-refurbishers Daoud and Aitken, these young people all spoke about how they had seen rangatahi locked out of the lives they deserve to lead by technology.

Spark puts its heads together

The crowd was then put to work looking at a series of profiles of imaginary Kiwis facing a range of barriers to digital inclusion. This follows a design thinking approach – starting with empathising with and deeply understanding the people your solution is trying to help.

The profiles represented the full gamut of New Zealand society, from teenagers in Auckland who aren’t sure how to keep themselves safe online, to provincial retirees struggling to deal with the isolation of a world that seems to be leaving them behind.

The brainstorms prompted out-of-the-box questions to try to solve the myriad issues at hand, ranging from questioning how the problem would be solved in a Disney movie or what the world would look like in a century if the issue is solved.

It’s a complex issue, the size of a generation, and the answers aren’t going to come from a single point of origin.

But with Spark being one of the biggest players in telecommunications and digital services in the country, infecting its workforce with the desire to bridge the gap could be an omen of a future in which New Zealanders have equitable access to life going on around them, whether it is through a screen or not.

Speaking to her employees, CEO Jolie Hodson said there was no silver bullet for the digital divide, but by making a long-term commitment to finding some of the many solutions that will be needed, the company will be ready.

“The most important thing is to start,” she said.

Spark is a partner of Newsroom.