Reports this week suggest a near-collision between an Australian satellite and a suspected Chinese military satellite.

Meanwhile, earlier this month, the US government issued the first ever space junk fine. The Federal Communications Commission handed a US$150,000 penalty to the DISH Network, a publicly traded company providing satellite TV services.

It came as a surprise to many in the space industry, as the fine didn’t relate to any recent debris – it was issued for a communications satellite that has been in space for more than 21 years. It was EchoStar-7, which failed to meet the orbit requirements outlined in a previously agreed debris mitigation plan.

The EchoStar-7 fine might be a US first, but it probably won’t be the last. We are entering an unprecedented era of space use and can expect the number of active satellites in space to increase by 700% by the end of the decade.

As our local space gets more crowded, keeping an eye on tens of thousands of satellites and bits of space junk will only become more important. So researchers have a new field for this: space domain awareness.

Three types of orbit, plus junk

Humans have been launching satellites into space since 1957 and in the past 66 years have become rather good at it. There are currently more than 8,700 active satellites in various orbits around Earth.

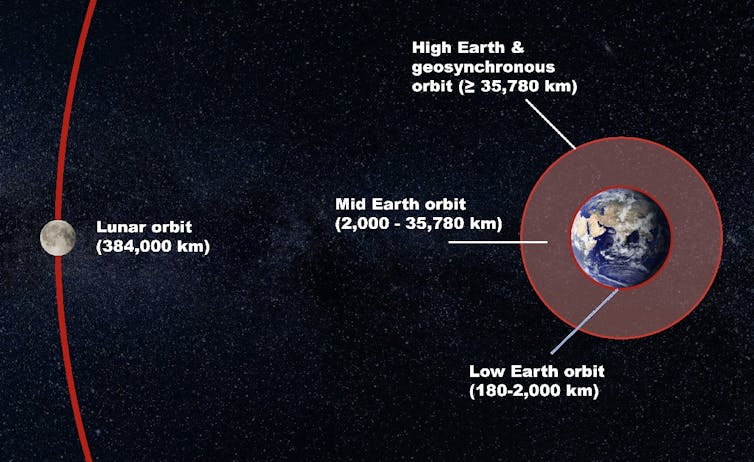

Satellites tend to be in three main orbits, and understanding these is key to understanding the complex nature of space debris.

The most common orbit for satellites is low Earth orbit, with at least 5,900 active satellites. Objects in low Earth orbit tend to reside up to 1,000km above Earth’s surface and are constantly on the move. The International Space Station is an example of a low Earth orbit object, travelling around Earth 16 times every day.

Higher up is the medium Earth orbit, where satellites sit between 10,000 and 20,000km above Earth. It’s not a particularly busy place, but is home to some of the most important satellites ever launched – they provide us with the global positioning system or GPS.

Finally, we have very high altitude satellites in geosynchronous orbit. In this orbit, satellites are upwards of 35,000km above Earth, in orbits that match the rate of Earth’s rotation. One special type of this orbit is a geostationary Earth orbit. It lies on the same plane as Earth’s equator, making the satellites appear stationary from the ground.

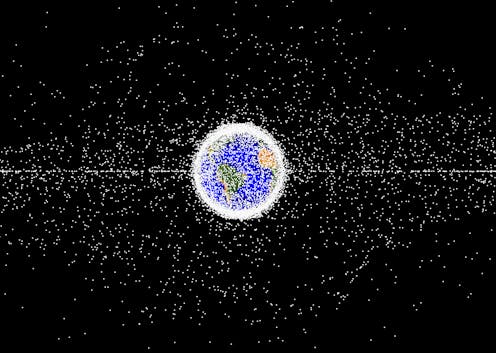

As you can tell, Earth’s surrounds are buzzing with satellite activity. It only gets more chaotic when we factor in space junk, defined as disused artificial debris in orbit around Earth.

Space junk can range from entire satellites that are no longer in use or working, down to millimetre-wide bits of spacecraft and launch vehicles left in orbit. Latest estimates suggest there are more than 130 million pieces of space debris, with only 35,000 of those large enough (greater than 10cm) to be routinely tracked from the ground.

How do we track them all?

This is where space domain awareness comes in. It is the field of detecting, tracking and monitoring objects in Earth’s orbit, including active satellites and space debris.

We do much of this with ground-based tracking, either through radar or optical systems like telescopes. While radar can easily track objects in low Earth orbit, higher up we need optical sensors. Objects in medium Earth orbit and geostationary orbit can be tracked using sunlight reflected towards Earth.

For reliable and continuous space domain awareness, we need multiple sensors contributing to this around the globe.

Below you can see what high-altitude satellites can look like to telescopes on Earth, appearing to stay still as the stars move by.

Australia’s role in space awareness

Thanks to our position on Earth, Australia has a unique opportunity to contribute to space domain awareness. The US already houses several facilities on the west coast of Australia as part of the Space Surveillance Network. That’s because on the west coast, telescopes can work in dark night skies with minimal light pollution from large cities.

Furthermore, we are currently working on a space domain awareness technology demonstrator (a proof of concept), funded by SmartSat CRC. This is a government-funded consortium of universities and other research organisations, along with industry partners such as the IT firm CGI.

We are combining our expertise in observational astrophysics, advanced data visualisation, artificial intelligence and space weather. Our goal is to have technology that understands what is happening in space minute-by-minute. Then, we can line up follow-up observations and monitor the objects in orbit. Our team is currently working on geosynchronous orbit objects, which includes active and inactive satellites.

EchoStar-7 was just one example of the fate of a retired spacecraft – the FCC is sending a strong warning to all other companies to ensure their debris mitigation plans are met.

Inactive objects in orbit could pose a collision risk to each other, leading to a rapid increase in space debris. If we want to use Earth’s space domain for as long as possible, we need to keep it safe for all.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank Sholto Forbes-Spyratos, military space lead at CGI Space, Defence and Intelligence Australia, for his contribution to this article.

Sara Webb receives funding through a research project co-funded by CGI technologies and SmartSat CRC, on work related to space domain awareness. She is a member of the Astronomical Society of Australia and American Society for Gravitational and Space Research.

Brett Carter is an Editor of the American Geophysical Union journal Space Weather. He receives funding from the Australian Research Council, SmartSat CRC and FrontierSI. He is also a member of the Australian Institute of Physics and the American Geophysical Union.

Christopher Fluke works for Swinburne University of Technology. He receives funding from the SmartSat CRC, including funding to support a research collaboration with CGI and RMIT. He is a member of the Astronomical Society of Australia and the International Astronomical Union.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.