As a provincial governor and former mayor of a medium-sized city with no parliamentary or cabinet-level experience, Lee Jae-myung was very much an outside bet to be South Korea’s next president. Then three higher profile rivals to be the ruling leftwing Democratic party candidate all dropped out: one was sent to prison for sexual assault, another died in an apparent suicide after being accused by his staff of sexual harassment, and a third is serving a prison sentence for election tampering.

That opened the way for Lee, a scrappy former factory worker who, in a nod to the veteran leftwing US politician, describes his ambition to be a “successful Bernie Sanders”. He is one of two men left standing in a presidential election race that has proved divisive and disreputable even by the carnivalesque standards of South Korea’s 35-year-old democracy.

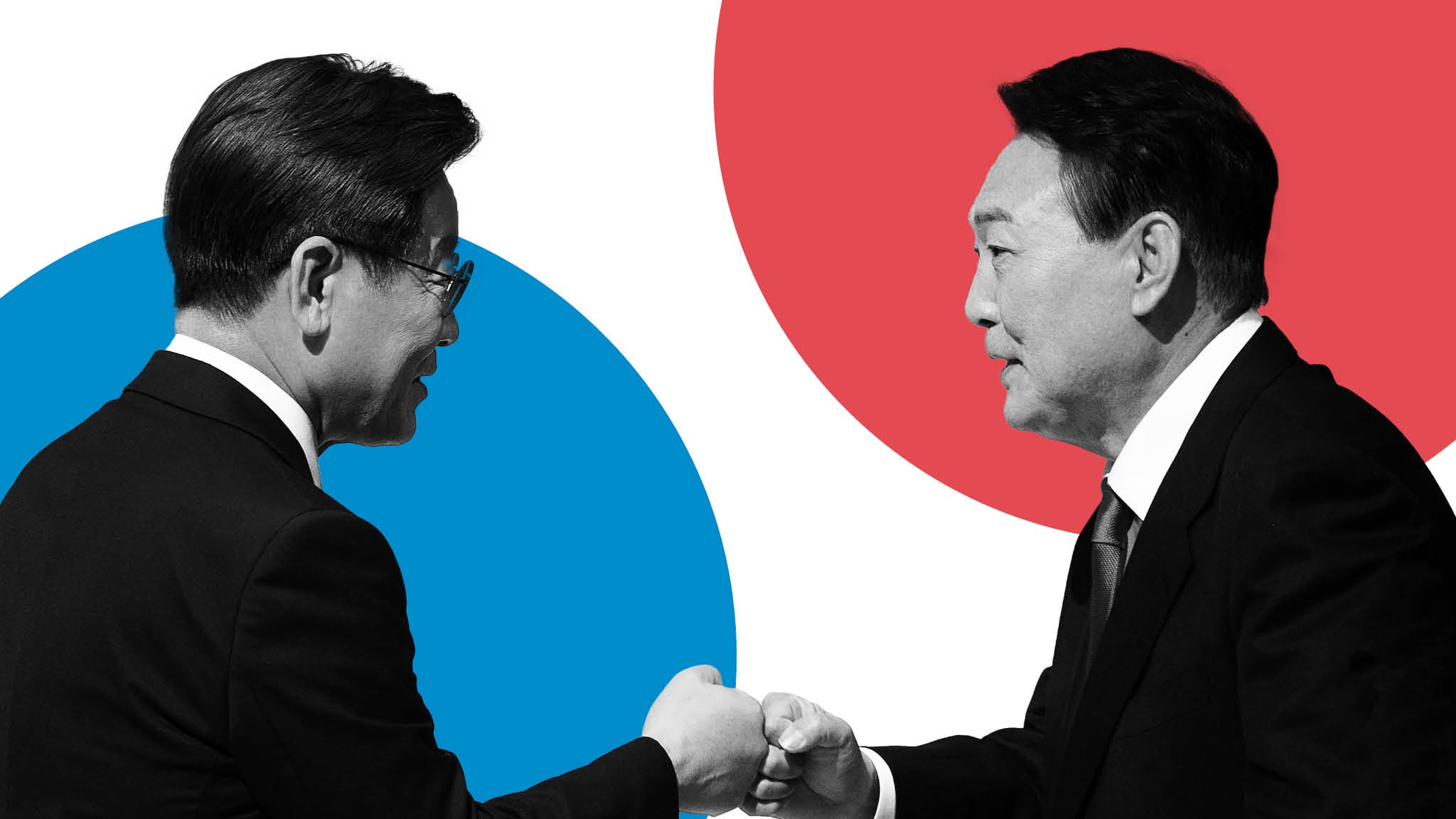

Lee and his conservative opponent Yoon Suk-yeol, a former chief prosecutor and political neophyte, are neck and neck in a contest that has been defined by scandal, mudslinging, family drama and insinuations of corruption, criminality, nepotism, fraud, dictatorial tendencies, superstitious practices and abuse of office.

The winner will take the helm of the world’s 10th largest economy, a vital US security ally and manufacturing powerhouse that sits at the heart of east Asia and harbours ambitions to lead the world in the development of next-generation technologies.

But he will also inherit an unhappy balancing act between the US and China, an unresolved conflict with North Korea, and mounting social and economic tensions as resentment builds over soaring asset and property prices, the growing wage gap between the country’s large conglomerates and SMEs, and challenges facing the young, women and minorities in particular.

South Korea’s reputation as a well-run country has been bolstered by its handling of the coronavirus pandemic, with the country achieving 4 per cent economic growth in 2021 while avoiding lockdowns and limiting total Covid-related deaths to less than 10,000. Observers warn of complacency, however, worrying that the country’s gladiatorial, mud-spattered politics — encapsulated by what has been dubbed the country’s “unlikeable election” — is hampering efforts to address long-term challenges.

“South Korea still has many strengths, including a very able bureaucracy and an active civil society that is increasingly intolerant of abuses and more willing to make demands of their leaders,” says Lee Sook-jong, professor of public governance at Sung Kyun Kwan University in Seoul. “But we have the lowest fertility rate in the world, our pension system is a ticking time bomb, and our increasingly complex society is not being represented.”

The outsiders

The March 9 contest, described by one smaller party candidate as a choice between a “drunk driver and a new driver”, features two main candidates divided by background and experience but united by their outsider status and strongman images.

Lee, 57, was born to a poor rural family in provincial eastern Korea, and still lives with the effects of a crushed arm from an industrial accident he suffered as a teenager. An advocate of fiscal expansion, he is seen by admirers as a formidable retail politician who gets things done — a reputation bolstered by his introduction of a “disaster basic income” payment in his province during the pandemic.

He also has baggage, not least criminal convictions for misrepresenting himself as a prosecutor while working as a lawyer, drink driving and interfering with the work of a public official.

He has also been accused of associations with organised crime amid an investigation into a giant kickback scandal relating to a property development in the city of Seongnam during his time as mayor. Lee has denied any such associations.

Korean voters remember his public offer to “pull my pants down” when faced with claims from an actress that she could prove her allegations of an affair by reference to a certain part of his anatomy, and a widely circulated recording of him launching a stream of obscene invective against his sister-in-law over a family dispute.

“I am ashamed every time I hear this is the most unlikeable election,” Lee said in January. “I sincerely apologise.”

Yoon, by contrast, is a product of Seoul’s elite. A career prosecutor, he rose to national stardom by leading the successful prosecution of conservative former presidents Park Geun-hye and Lee Myung-bak on corruption and bribery charges.

His reputation as a graft-buster earned him the position of prosecutor-general in the progressive administration of Democratic incumbent Moon Jae-in, but he fell out with the government after launching an investigation into his own justice minister over an alleged college admissions scandal. Having resigned from the Moon administration in 2021, he went straight into politics, securing the nomination of the opposition People’s Power party just a few months later.

The 61-year-old has been accused by opponents of practising what they call “K-Trumpism” after he described a former authoritarian president, Chun Doo-hwan, responsible for the massacre of protesters in 1980 as “good at politics” (Lee too has praised former authoritarian leaders). He has also been subjected to widespread ridicule after the Korean press aired allegations — which he denies — of longstanding associations with shamans and fortune-tellers and a reported predilection for anal acupuncture.

Despite South Korea having the widest gender pay gap in the OECD, and a wave of digital sex crimes against Korean women, Yoon has pledged to abolish the country’s ministry of gender equality, blaming feminism for the country’s low birth rate. He has also been accused of “red-baiting” after he posted a picture on Instagram of himself shopping for groceries, with the contents of his trolley spelling out: “Exterminate Communists”.

“These are the two worst presidential candidates that South Korea has faced in the democratic era,” says Gi-wook Shin, professor of contemporary Korea at Stanford University. “Whoever wins, I worry about the state of South Korean democracy.”

‘A winner-takes-all fight for survival’

South Korea’s political class remains defined by the authoritarian regime that ruled the country between the 1950s and the late 1980s.

On one side is a conservative coalition with roots in the regime and its allied business conglomerates — hawkish on China and North Korea, strongly pro-American, conciliatory towards Japan, and with close connections to socially conservative Christian movements. On the other is a progressive coalition with roots in the democratic opposition to the regime — conciliatory towards China and North Korea, less enthusiastic about America’s role on the Korean peninsula, and more openly antagonistic towards Japan.

Led by former dissidents, many of whom suffered at the hands of repressive state institutions, progressives see their historic role as rooting out the remaining corrupt vestiges of the old authoritarian order, and pursuing peace and reconciliation with North Korea. But many conservatives regard their progressive counterparts as hypocrites, bent on revenge and soft on national security.

“We need to remember that South Korea went through a really brutal authoritarian period, and did not have a serious transitional justice process,” says Erik Mobrand, Korea policy chair at the Rand Corporation. “The country has actually moved on remarkably — in many ways it has been a case study in overcoming that sort of violence.”

The winner of the country’s first democratic presidential election in 1987, army general Roh Tae-woo, was jailed during the presidency of his conservative successor on bribery, mutiny and treason charges relating to the 1980 massacre of protesters in the southern city of Gwangju. But it was the investigation and subsequent death of progressive president Roh Moo-hyun in the late 2000s under his conservative successor, Lee Myung-bak, that marked an escalation of the simmering conflict between conservatives and progressives.

Roh jumped off the side of a mountain in 2009 under the pressure of a bribery investigation and it was under current president Moon Jae-in, Roh’s protégé, that Yoon oversaw the prosecution and imprisonment both of Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye.

“The imprisonment of former dictators was part of the democratisation process,” says Lee Sook-jong, “but the attempt to imprison Roh created a new dynamic.”

She argues that this political dysfunction is exacerbated by other inheritances from the authoritarian period. The constant threat of conflict with North Korea and the former regime’s economic model of state-directed capitalism means that power is concentrated in the Blue House, giving the president huge formal and informal influence over nominally independent institutions — including the all-important state prosecutors.

“There is a very strong expectation from the public, rooted in the authoritarian era, that the president exists to solve all their problems,” says Lee Sook-jong. “Unfortunately there is a lack of moderation at the elite level — an inability to compromise, and a willingness to use public institutions to investigate, punish and purge opponents.”

“This makes every election a winner-takes-all fight for survival.”

Muddying the picture is the role of the all-powerful chaebol — family-owned conglomerates historically intertwined with the upper echelons of the Korean state. Both Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye were imprisoned in part because they each took millions of dollars from successive executives at Samsung, the country’s biggest company by market capitalisation.

35 years of democratic presidential elections

1987

Roh Tae-woo, conservative. He was convicted in 1996 of treason, mutiny and corruption, and sentenced to 17 years in prison. He was pardoned in 1997

1992

Kim Young-sam, conservative. He was the first civilian president in 30 years

1997

Kim Dae-jung, progressive. He was the winner of Nobel Peace Prize in 2000

2002

Roh Moo-hyun, progressive. He was investigated for bribery after he left office. He died by suicide in 2009

2007

Lee Myung-bak, conservative. He was convicted in 2018 of bribery, embezzlement, abuse of power and sentenced to 15 years in prison, and is still detained

2012

Park Geun-hye, conservative. She was impeached in 2017, convicted in 2018 of corruption and abuse of power, and sentenced to 22 years in prison. She was pardoned in 2021

2017

Moon Jae-in, incumbent president, progressive

Park Sangin, professor of economics at the graduate school of public administration at Seoul National University, says that chaebol power continues to distort the economy and corrupt Korean public life.

He argues that the fate of the Korean economy — and with it, the fate of each individual presidency — remains dependent in large part on the investment decisions of a handful of companies and the families that run them. In turn, those companies depend on the good graces of regulators and prosecutors who are beholden to the Blue House.

The result, says Park Sangin, is a culture of reciprocal “favours” that extends to financing for favourable media coverage and lucrative post-career sinecures. It means that when a new administration takes over, it has all the ammunition it needs to launch investigations into its predecessor.

“It’s not just politicians who are beholden to chaebol money — it is lawyers, judges, bureaucrats and journalists too,” says Park Sangin. “No one is free from it.”

Lee Sook-jong adds: “In Korea, a president rules for five years. But a chaebol family rules forever.”

The power of the Blue House

Moon Jae-in has a 40 per cent approval rating and when he formally passes the presidency to his successor in May, he will probably do so with the highest ratings of any outgoing South Korean president in the post-1987 order.

Admirers cite the country’s impressive economic growth over the course of his term and his sure-footed response to the coronavirus pandemic, while polls suggest that many Korean voters also appreciate Moon’s tireless pursuit of diplomacy with the North.

But critics contrast Moon’s achievements unfavourably with the promises of comprehensive reform on which he was elected, following mass anti-corruption protests and Park Geun-hye’s impeachment.

“As I promised during my campaign, I will prioritise creating jobs. At the same time, I will put chaebol reform at the forefront,” Moon pledged in his inauguration speech in 2017. “Under the Moon Jae-in administration, the ‘collusive link between politics and business’ will completely disappear.”

That made Moon’s acquiescence last year in the early release of Samsung heir Lee Jae-yong, who was serving a prison sentence for bribing Park Geun-hye, all the more disappointing for reformers.

Others blame Moon for perpetuating the country’s cycle of political conflict by pursuing what he described as the “eradication of deep-rooted evils”, which many interpreted as a blanket purge of conservatives.

“Moon was elected on a mandate to reform and upgrade South Korean democracy, but he missed a golden opportunity,” says Stanford’s Gi-wook Shin. “His generation was better at fighting for democracy than practising it.”

Some analysts worry that Moon’s failure to reform the country reflected not a lack of will, but the near-insurmountable difficulty of instituting structural reforms within the present system.

The power of the Blue House is tempered by a one-term limit on all presidents. In practice, say observers, this stifles meaningful reform as presidents chase eye-catching initiatives and short-term wins before their authority starts to drain away over the final couple of years of their five-year terms.

Park Sangin of Seoul National University argues that until South Korea’s political class summons up the courage to loosen the grip of the chaebol over the economy and politics, the country’s political and economic progress risks being hampered or even derailed as social inequalities continue to mount.

“Economic concentration is the root of the structural problems now faced by the economy and society,” says Park Sangin. “It worked while we were still a developing country. But it stifles innovation, blocks reform, and exacerbates inequality. We talk about Japan’s ‘lost decades’, but I fear South Korea is entering lost decades of its own.”

But Park Chong-hoon, head of Korea research at Standard Chartered, argues that the country’s success over recent decades demonstrates the system’s enduring strengths.

“Korea’s economic policy is ultimately run by its technocrats, and they run the system in a clean and stable way,” says Park Chong-hoon. “It is true that the chaebol are not always run in the wider public interest, and that inequality is a problem. But it is hard to look at the Korean economy and say it is malfunctioning.”

Fei Xue, country analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit, adds: “South Korean politics is certainly confrontational, and there are a lot of scandals. But overall, civil liberties are respected, the rule of law is upheld, and citizens are motivated and engaged.”

Commentators note the irony that the frustration felt by many Koreans towards their warring political class has forced both parties to reach for populist outsider candidates — one promising economic justice, the other criminal justice — both of whom appear likely to perpetuate the conflict.

“If Lee wins, the Democratic party controls the Blue House and the parliament, making it hard for them to be held to account,” says Stanford’s Gi-wook Shin. “But if Yoon wins, he may feel that the prosecutors’ office is his only weapon.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022