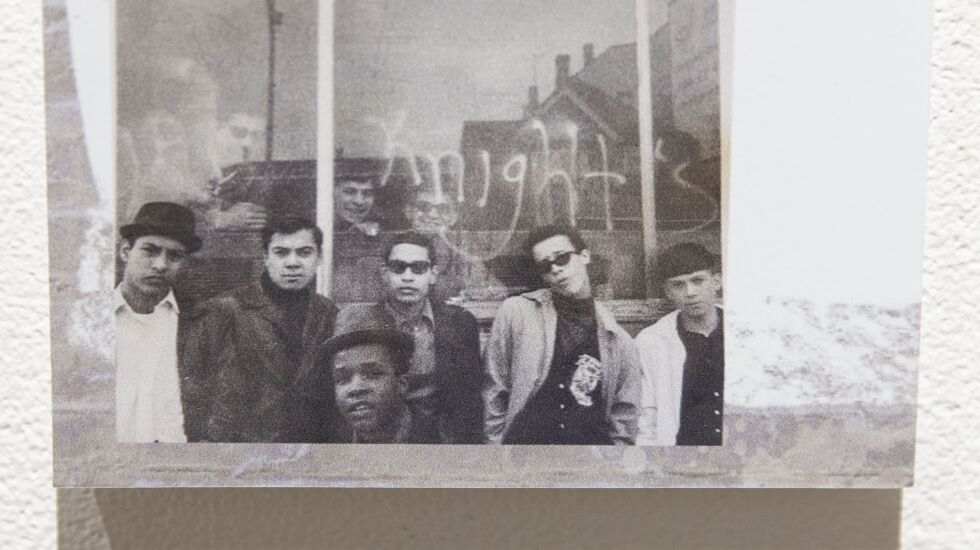

Walk inside the Intuit gallery, and one of the first paintings you notice is “Brothers,” by Roman Villarreal.

Completed by the South Chicago artist in 2021, it shows him at age 19, hanging out.

His younger brother, Don, is at far left; Roman is in the middle. Based on a photo taken when Roman was home on leave from Vietnam where he was drafted to serve in the Army and shows the conviviality of life before the steel mills closed.

“I’m sharing experiences that happened in this community with the world, what happened in this community during the peak of the steel mills and then when the steel mills disappeared,” said Villarreal, now 72.

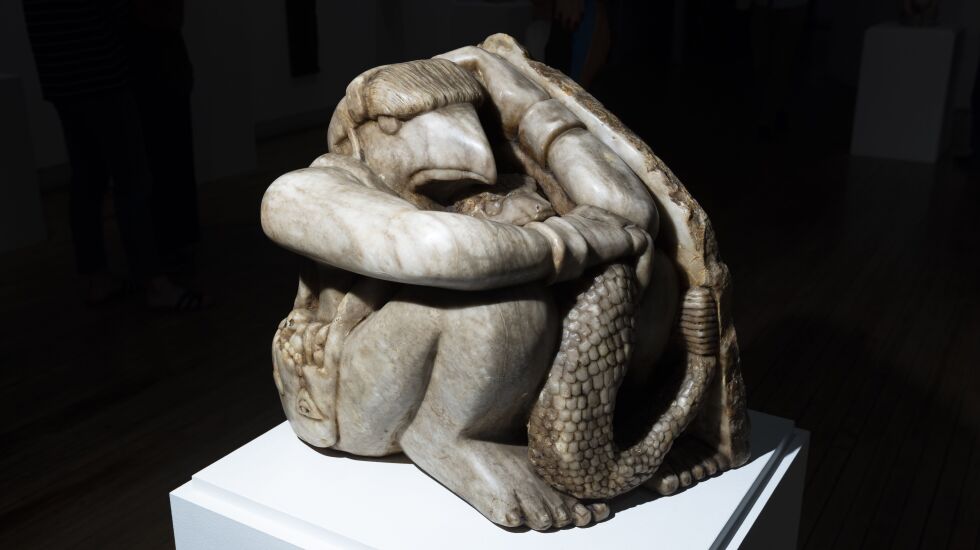

The show, “Roman Villarreal: South Chicago Legacies,” is on view until January at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, 756 N. Milwaukee Ave. It spans the self-taught artist’s career, from a wood carving from the ‘70s to a limestone sculpture from 2022. His first major retrospective, it documents the legacy of Mexican immigrant families that moved to South Chicago for work and struggled when industry moved elsewhere.

“He’s this artistic historian of his neighborhood,” said show curator Alison Amick.

The chief curator at the River West museum for the past seven years, Amick designed the gallery space to be a view into Villarreal’s life from the street.

“I thought it would be really nice to enter into the space and have the feeling of entering into Roman’s neighborhood and Roman’s world,” she said.

Next to “Brothers” is “Hanging out on the Porch.” It shows how before fears of gang violence took over, people used to spend time on the front porch. Several people stand and sit, drinking beer; a mother holds a baby and a father has his arm around a daughter.

“Everybody’s plan was to go to work in the mill, do your 30 years and retire and live the good life,” Villarreal said.

Villarreal’s father moved the family to Chicago in 1949 to work in the mill and Roman worked there after Vietnam.

Then, in the ’70s, many of the mills started to closed.

“We almost made it to middle class and then when the mill closed it turned everybody into a spin. Life changed completely for a lot of us” he said.

Addiction, poverty and violence followed.

A painting from the ’80s titled, “They die on the throne,” shows a young man shooting up on a toilet. A hummingbird, which Villarreal explained represents “the warrior spirit,” hovers at his shoulder, symbolizing that he is a Vietnam veteran.

Rather than gangs, Villarreal turned to art.

“The gift of shaping and the arts is what actually what kept me above water during the hard period of time when everything was going bad.”

He had enjoyed making art since he was young but never pursued it. Out of work, he began producing and was invited to a group show, after which he delved into it full-time.

Not everyone he was close to found a way out.

“Everybody in this community has paid the price. Either one of their relatives or loved ones was killed, or one of your relatives killed somebody and they’re locked up for the rest of their lives,” he said.

He hesitates to identify people in his work, aside from “Brothers,” but will say one other set of pieces in the show — which he never intended anyone to see — is based on his brother Don.

“That one basically is a tribute to one of my younger brothers that became addicted to life,” Roman said.

“Lost I” shows a man stuck behind bars with a syringe held perpendicular against the vertical bars. “Lost II” shows a woman filling a chalice from her breast with a parrot on her shoulder. They stand for the two drugs common then, heroin and cocaine.

Villarreal presumes his brother’s death in the ’80s was from an overdose.

“It’s a reminder of when somebody took the wrong turn in life. It’s a reminder to me of what happened. That would be the message,”

And to Don, Roman added, the message is: “Yes, we know you fell through the cracks.”

Michael Loria is a staff reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times via Report for America, a not-for-profit journalism program that aims to bolster the paper’s coverage of communities on the South and West sides.