On the morning of Wednesday, 16 June 1976, young students from schools across Soweto set out on a march through the sprawling black township outside Johannesburg. The march was to amplify their opposition to the apartheid government’s new school-language policy that would see Afrikaans replace English as their main medium of instruction in several key subjects.

Before the march began, they were confident. They knew the risks that they faced – “we decided that there should be no placard inciting the police as such, one activist put it afterwards, because "we wanted a peaceful demonstration – it had to be disciplined”. Even so, they were excited, believing that the march would be a carnivalesque event, “a Guy Fawkes thing,” as one put it – an event in which the world would be turned upside down.

Their excitement buoyed them in the early hours of the morning, as thousands of students joined in the march. But this atmosphere did not last.

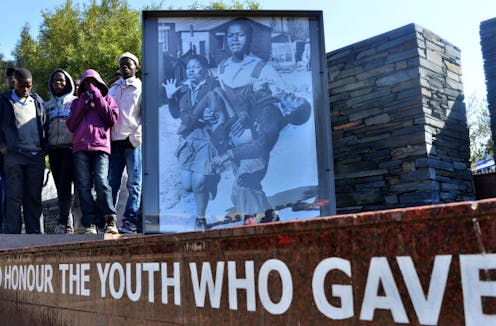

A few hours into the march, heavily-armed members of the South African Police confronted a crowd of students near the Orlando West High School. They fired tear-gas at the students, and then, moments later, fired live ammunition. In the moments that followed, they shot and killed Hector Pieterson an eleven-year old child. As if energised by this death, the police continued to assault and kill students.

In the hours that followed, another 10 people died at the hands of the police. Over the next three days, at least 138 people died. And the deaths did not stop. Throughout the rest of the year, the police and military would patrol Soweto and many other sites of popular resistance, and use whatever force they deemed necessary to suppress dissent, quash protest, and establish order.

These protests reignited the public flame of resistance, and helped re-make the opposition to apartheid. They provided a model and an example for activists to follow into the 1980s.

June 16 in perspective

Today, 46 years later, South Africa commemorates June 16th as National Youth Day.

It is no doubt important to do this, and to remember the sacrifices and struggles of the past. But in commemorating this day, South Africa runs the risk of sacralising these events – of lifting them out of their historical context, stripping them of their political complexities, and remaking them into a mere symbol, something that only needs to be remembered once a year and then forgotten the rest of the time.

In my book, published on the eve of the 40th anniversary of June 16th, The Road to Soweto, I argued that the sacralisation of this singular day has distorted understandings of South Africa’s post-apartheid democracy.

It is now almost trite to suggest that the political order of post-apartheid South Africa was forged in conference rooms and around negotiating tables in the 1990s; that the conversations, debates, and arguments between the representatives of the negotiating parties are what shaped the terms of the country’s political institutions and laws; and that the country constitution is best understood as the product of an elite idealism. All of this is at least partially true.

What is wrong with this vision is that it leaves out the role of ordinary people taking to the streets –- the role of protest, of marches, of popular organisation, dissent, discordance, creativity, and struggle –- in making the post-apartheid democratic order.

It presumes that the state is the beginning and the end of the political order; that democracy is only achievable through representation; and it presumes that “the people” are a political resource to be deployed by elite actors (whether these be politicians or intellectuals, revolutionaries or revanchists) and not a source of political ideas in themselves.

But this is not true.

Making democracy

While democracy may be encouraged and entrenched through institutions and ideas, it is first made through action. The students who marched on 16 June 1976 did more than simply register a political opinion.

They enacted an alternate form of politics. By gathering and marching together, and by acting together they constituted themselves as political agents – as people who already possessed the kind of agency that the apartheid state denied they could ever claim. And by marching side-by-side – regardless of their age and gender, status and authority – they constituted themselves as a democratic force, as a community of equals.

As I’ve argued before, this form of politics is not merely a product of the past, not merely a product of the anti-apartheid struggle. Instead, it has marked – and still marks – popular dissent and democratic organising in South Africa since the end of apartheid.

Over the past two decades, such forms of popular democracy have marked the struggles of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack-dwellers movement that organises in informal settlements across South Africa. It has driven the activism of the Treatment Action Campaign, and its grassroots work to force the state to provide anti-retroviral medication. And it has led to labour activists, unions, and other communities achieving significant changes in the platinum mining industry.

The roots of democracy lie in these actions, in these claims to agency and equality. These acts are themselves rooted in a complex pattern of joy and anger – in the desire to turn the world upside-down, and emerge out of specific historical and social contexts. But they can transcend these moments. They can open up a channel, create a model, and instigate a revolution.

In other words: if the events of 16 June 1976 are seen as an ongoing part of the process of constituting democracy in South Africa, then we can see it as part of contemporary political struggles – and not just as an historical event, safely sealed away in the past.

The marches, protests, and pickets that mark contemporary South Africa are the source of a continually-renewing (and, perhaps, continually-mutating) democracy. The institutions of the state may shape the ways in which this democracy develops, but they do not create it. “The people” make politics.

At this moment, as South Africa’s political elites continue to be mired in scandal, as the state bureaucracy struggles to fulfil its functions, and as scholars and activists question the legitimacy of the constitutional settlement, the anniversary of the uprising of 16 June 1976 in an opportunity to think about what post-apartheid democracy can mean.

It does not only mean the forms and institutions that define the democratic state. It must also mean the ongoing acts of ordinary people, the acts that assert and imagine democracy on the streets over and again.

Julian Brown does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.