Pacing along the dark corridors of a rundown five-storey building in Johannesburg's crime-ridden township of Alexandra, Duduzile Mthembu says she has been trying to persuade young residents to vote.

Constructed in 1970 by the apartheid regime to house male workers coming from the eastern province of KwaZulu-Natal to work in Johannesburg's mines and industry, the red brick hexagonal estate, known as Madala hostel, is now home to thousands.

Mostly ethnic Zulus, they live in cramped rooms with gated doors, broken windows and leaking roofs.

Like most here, 57-year-old Mthembu supports the Zulu nationalist Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

But party loyalty is fading with a younger generation seeing no hope in politics, even as South Africa holds its seventh democratic election, 30 years after the advent of democracy.

"They say there is no change and no reason to vote. I am trying to talk to them," she said, sporting an IFP T-shirt.

Surrounded by poverty and decay, it is hard to be optimistic.

Most communal toilets have no running water and stink of urine.

Goats frolic near garbage dumps and sewage spills, as residents hand wash their clothes and hang them to dry in the yard.

Part of the top floor burnt down in a fire more than a decade ago and has not been repaired.

Outside, brick and corrugated iron shacks topped by white satellite dishes are crammed against one another.

Zakhele Zondo, 41, moved here in 2002 from Ulundi, the ancient capital of the Zulu kingdom, looking "for a brighter future".

He has not found it. But making a "small salary" as a driver he is able to support a large family back home, sending money every month.

"This place is no longer good for people, it's too old," he said of his accommodation -- a small room with no heating and two single beds he shares with another man.

Traditional animal skin garments hang from a string near rusty lockers plastered with faded paper cut-outs of bare-chested Zulu girls and a picture of a former South Africa football team posing before playing France in the 1998 World Cup.

After preparing beef and pap -- a corn meal -- Zondo said he will go vote for the IFP, crediting the party with taking good care of his hometown.

But he is not excited about it.

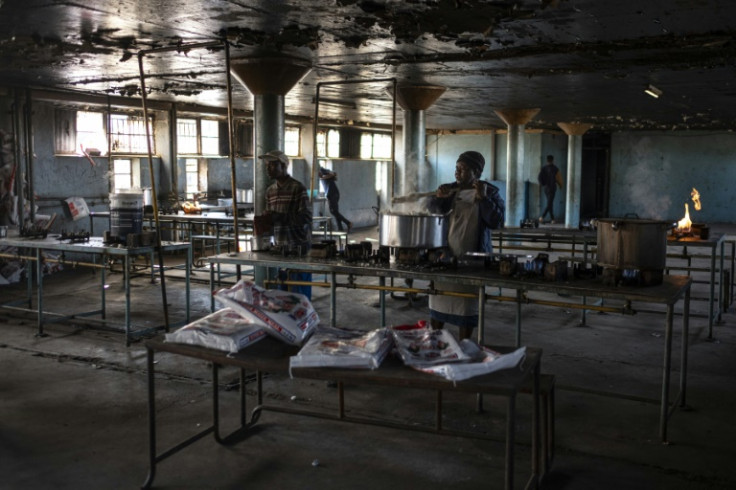

"There is nothing special about voting anymore," he said, as children played with a paper ball strapped together with tape in the shared kitchen.

Siphokuhle Mfuphi, a 33-year-old armed cash-in-transit guard who lives in a shack attached to the building, feels the same.

"You must work for yourself. As a man you can't depend (on politicians), you must change things by yourself," he said.

Party representatives come ask for votes before elections and disappear afterwards, he complained.

Standing outside a shabby ground floor toilet where men bring buckets of water for showering, a 23-year-old in jeans, flip flops and green cap, who preferred not to give his name, said he would not vote.

"There is no point," he said.