It’s a common scenario: you decide to go out for dinner and fancy something different. So, you look to online reviews to help you make your dining choice.

If you trust a review of a restaurant and then it doesn’t reach your expectations, it’s probably not a huge deal. But should we feel as comfortable about testimonials about health-care services?

These are commonplace in other countries, and the law banning positive reviews of medical services is about to change here in Australia.

Removing the ban

Much of Australia’s health-care workforce is regulated by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). The agency’s registration scheme is broad, including medical doctors, dental practitioners, nurses and midwives, as well as many others.

The scheme is set out by nationally consistent law, enacted in each state and territory, commonly referred to as the National Law.

A recent bill tabled in the Queensland Parliament will change the National Law. One of the amendments is the removal of the current ban on regulated health services advertising using positive testimonials from patients.

Testimonials already exist in health care

Despite the current ban, a quick search on Google reveals there are lots of reviews about a huge variety of health-care services already, apparently written by patients and carers.

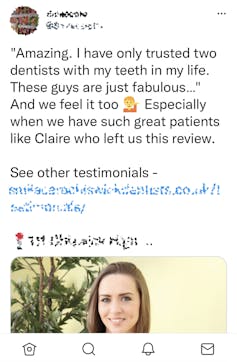

The current regulations around health-care advertising don’t prevent patients from independently voicing their opinions and feelings about the care they’ve received. But health providers are banned from using testimonials to advertise on platforms that they control, such as a practice website or social media page.

Furthermore, there are health practitioners who use testimonials to advertise already; they either don’t know about the regulations or choose not to follow them.

Another reason lifting the ban makes sense is that AHPRA simply doesn’t have the resources to monitor all health-care advertising in Australia. It relies on complaints from the public or other health practitioners to notify against advertising that breaches the current standards.

Along with AHPRA holding practitioners who are flagged as doing the wrong thing to account, health businesses misusing testimonials may also face regulatory action.

In 2020, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission fined review and booking website HealthEngine $2.9 million for publishing misleading patient reviews and ratings.

But in a digitally interconnected world, online testimonials from other jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom and the United States, where health-care testimonials are not as strictly regulated, are easily accessed by Australian consumers. So enforcement is hugely challenging.

Read more: Googling for a new dentist or therapist? Here's how to look past the glowing testimonials

‘Word of mouth’ might not be that powerful

The prevailing marketing wisdom is that testimonials are powerful persuaders. Our research was the first to examine how health consumers might engage with testimonials to make decisions about what services to access. We asked more than 1,500 health consumers about the ways they used health advertising and testimonials.

We found that while participants found testimonials helpful, there was concern about their reliability in the context of health care. Only a small number of participants felt they could spot a “fake” review.

Previous research suggests online testimonials help consumers save time in decision-making.

Our study also found most participants felt health-care comparison websites were trustworthy sources of information and reviews of services.

Is removing the ban a bad idea?

Despite the intention of the National Law being to protect the public, the 2014 review of the National Scheme found a wide range of stakeholders did not support the outright ban on testimonials in health advertising. Many said this prohibition meant consumers couldn’t comment much on their health-care experiences.

It could be argued testimonials about health services are an important instrument in the democratisation of health care. Patients are empowered to access the experiences of other consumers and share their feelings about their own care.

When we examined the attitudes of private dentists to commercial practices like advertising, many felt such engagement could promote equality between patients and professionals.

This might be true in part, but advertising is fundamentally designed to sell. When it comes to advertising health care, we might value the potential for marketing to provide education on what services might be available – but we should be careful people are not sold care they don’t really want or need.

Read more: Dr Google probably isn't the worst place to get your health advice

The potential for misleading reviews

In short, we probably don’t need to be more concerned about “word of mouth” health reviews than we are now – even if the law changes.

It is clear testimonials in any sector can be misleading. And we also know some members of the public will struggle to assess the legitimacy of health-care reviews and testimonials.

Consumers should be able to use testimonials to inform themselves about health services, but no one should rely on them exclusively. Health consumers should also be guided by other sources of information, such as advice from a trusted health practitioner, to help inform their decision-making process. There is also nothing inherently unscrupulous about a health-care provider using a sincere testimonial or review to spread the word about the care they offer.

But ultimately, if something seems too good to be true, it possibly is. Health-care consumers should feel empowered to research their options without feeling they are being oversold care that might not be right for them.

Alexander Holden has received funding from the Australian Skeptics supporting research into health advertising. He has also received research funding from the Dental Council of NSW and NSW Health. Alexander is a Director of the Australian Dental Association NSW Branch, Filling the Gap and the Australasian College of Legal Medicine.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.