The thought of prisoner of war camps is not one that brings to mind images of regular music concerts filled with upbeat songs and humour.

It almost feels like you're crossing a line just to consider the thought. But the reality is, as horrible as these camps were, they were also places that saw a steady stream of music being created in a bid to boost morale.

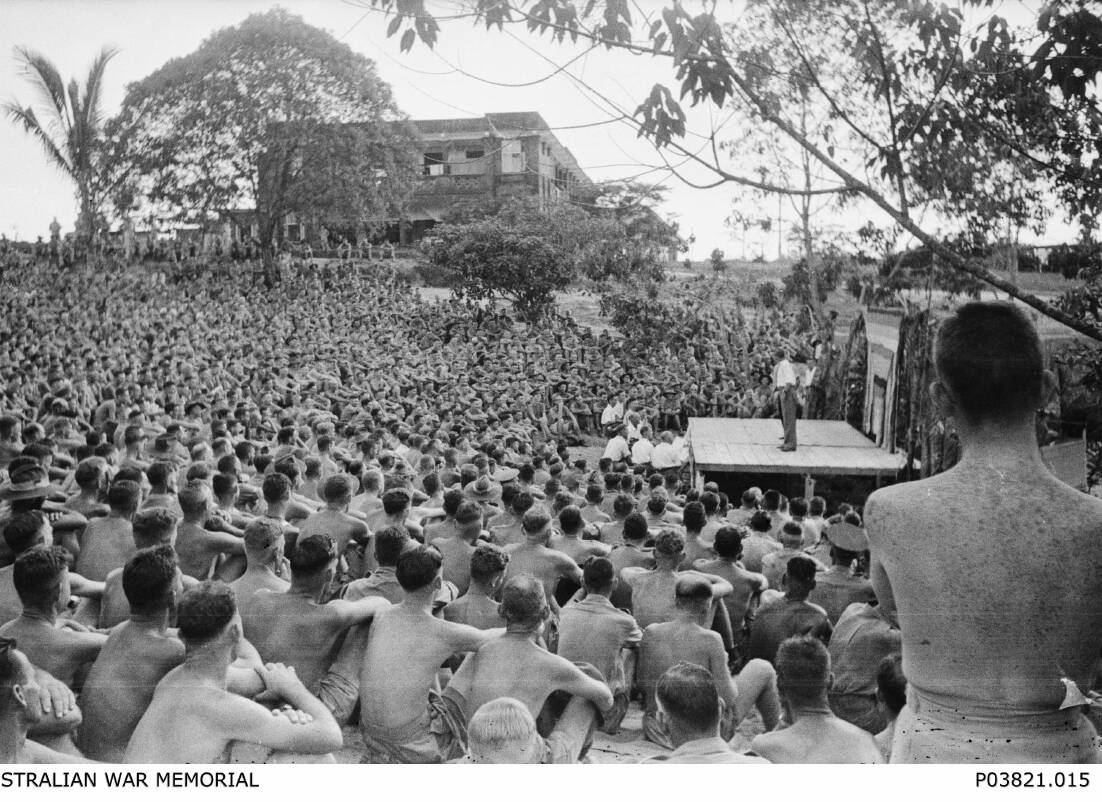

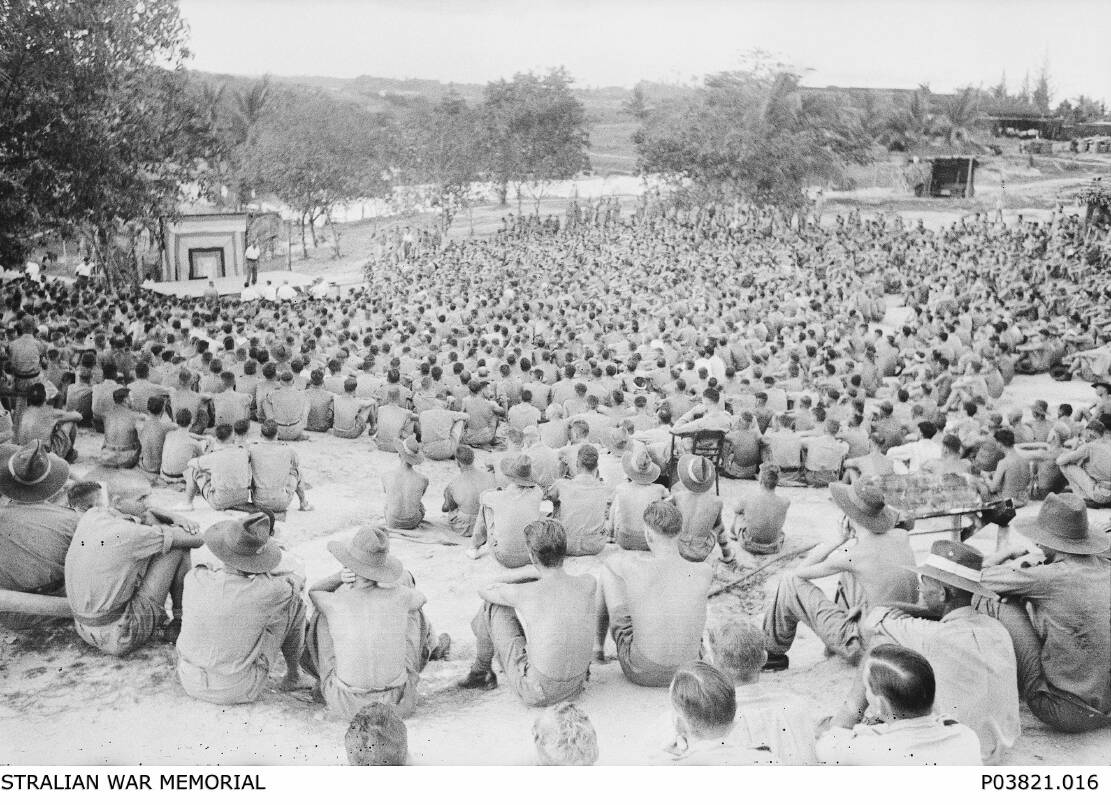

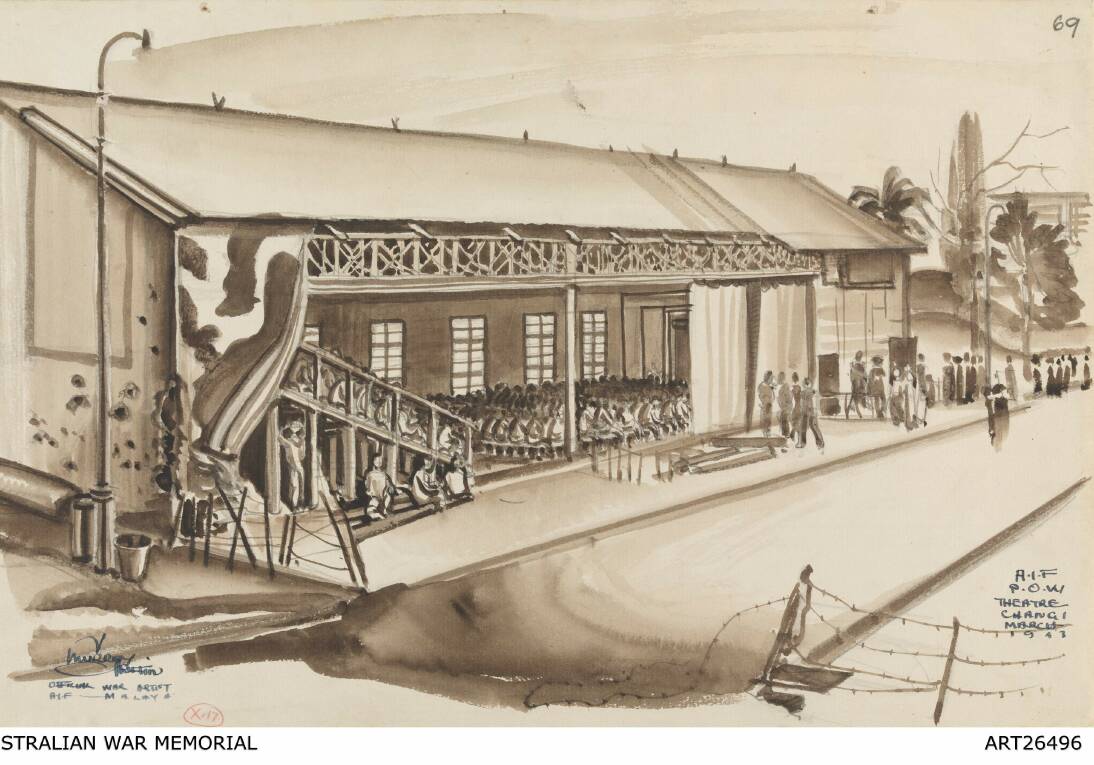

Singapore's Changi alone saw more than 240 theatre shows between 1942 and 1945, thanks to the AIF Changi Concert Party. At the same time, in a Sumatran prisoner of war camp, the Women's Vocal Orchestra, were boosting morale by taking complex orchestral works and condensing them down to perform as four-part vocal harmonies.

It's this lost piece of cultural history, that even in the months after POWs returned home, Australians didn't want to believe happened.

But now, more than 70 years later, there is a group of Australians bringing this music back to the stage, telling the accompanying stories that go along with it.

Lead by The Flowers of Peace - a not for profit organisation dedicated to music connect to the wars - along with the support of Australian War Memorial, Department of Veterans' Affairs and Australia Council for the Arts, POW Requiem is a concert aiming to acknowledge the past and importance that music held during this time.

The Changi Songbook

The Australian prisoners captured by the Japanese during World War II were stationed at the Changi camp where they suffered from hunger and many atrocities.

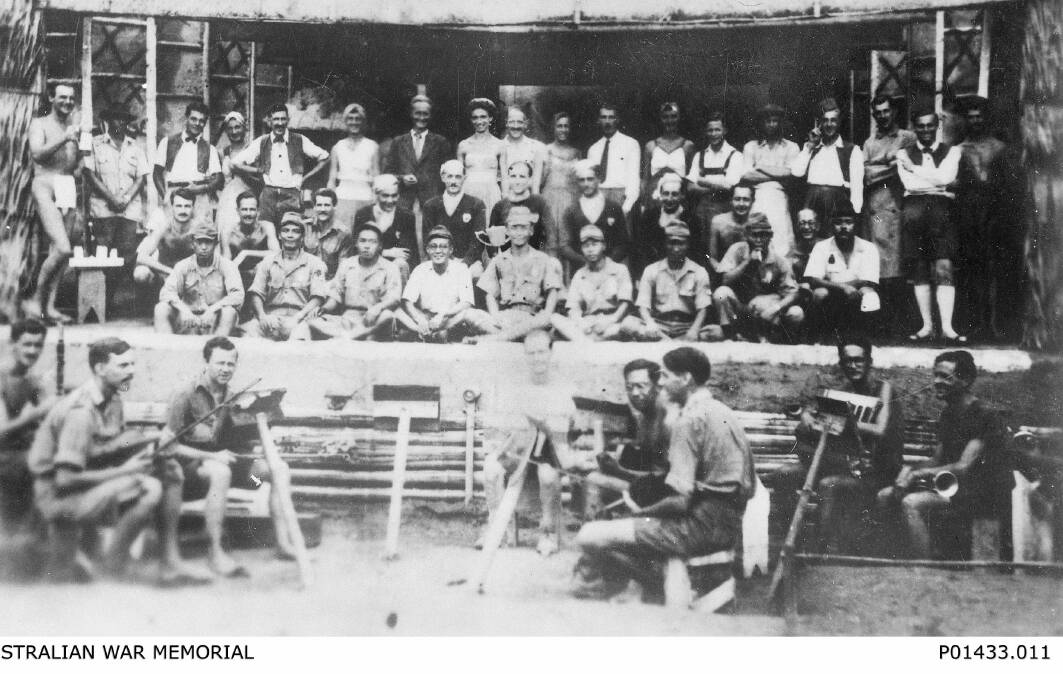

Still, as a way of lifting spirits - and providing a form of good medicine, so to speak - a number of the incarcerated found a way to lift the spirits by producing and performing weekly shows. These men would soon become known as the AIF Changi Concert Party.

"You wouldn't expect that people who are worried about food and things like that would prioritise culture, but it's almost the first thing they do whenever they arrive in a camp, is they set up concert parties, a group of people to play concerts," Flowers of Peace director Chris Latham says.

"So they find out inside this prisoner population who can play the trumpet, who can play the violin, all that sort of stuff. And then they start just making shows.

"In Changi there was a roster system so every prisoner got to see a show every fortnight. You can see a new show and everyone was guaranteed that. And the reason was because the first thing that happens when you're imprisoned is that everyone gets very depressed."

In the case of Changi, these performances began the way they all did - through memory. The concert would play anything and everything that they could remember from their pre-war lives. And when they couldn't remember any more, they started to write their own music. Songs that, for the most part, had nothing to do with the horrors that they were facing.

Latham calls them vitamins for living. Songs that were highly concentrated forms of energy and emotion that they weren't getting anywhere else. Songs full of optimism; uptempo jazz numbers that had you tapping your foot; lyrics that included jokes about life as a prisoner. And above all, there were songs about romantic love - something that in this male-only camp was scarce.

As the war came to an end, the prisoners voted on their favourite songs to include in what would become known as The Changi Songbook - a collection of 24 songs that were written down and distributed to the prisoners. A memento, if you like, of what was one of the brighter moments in what was otherwise hell.

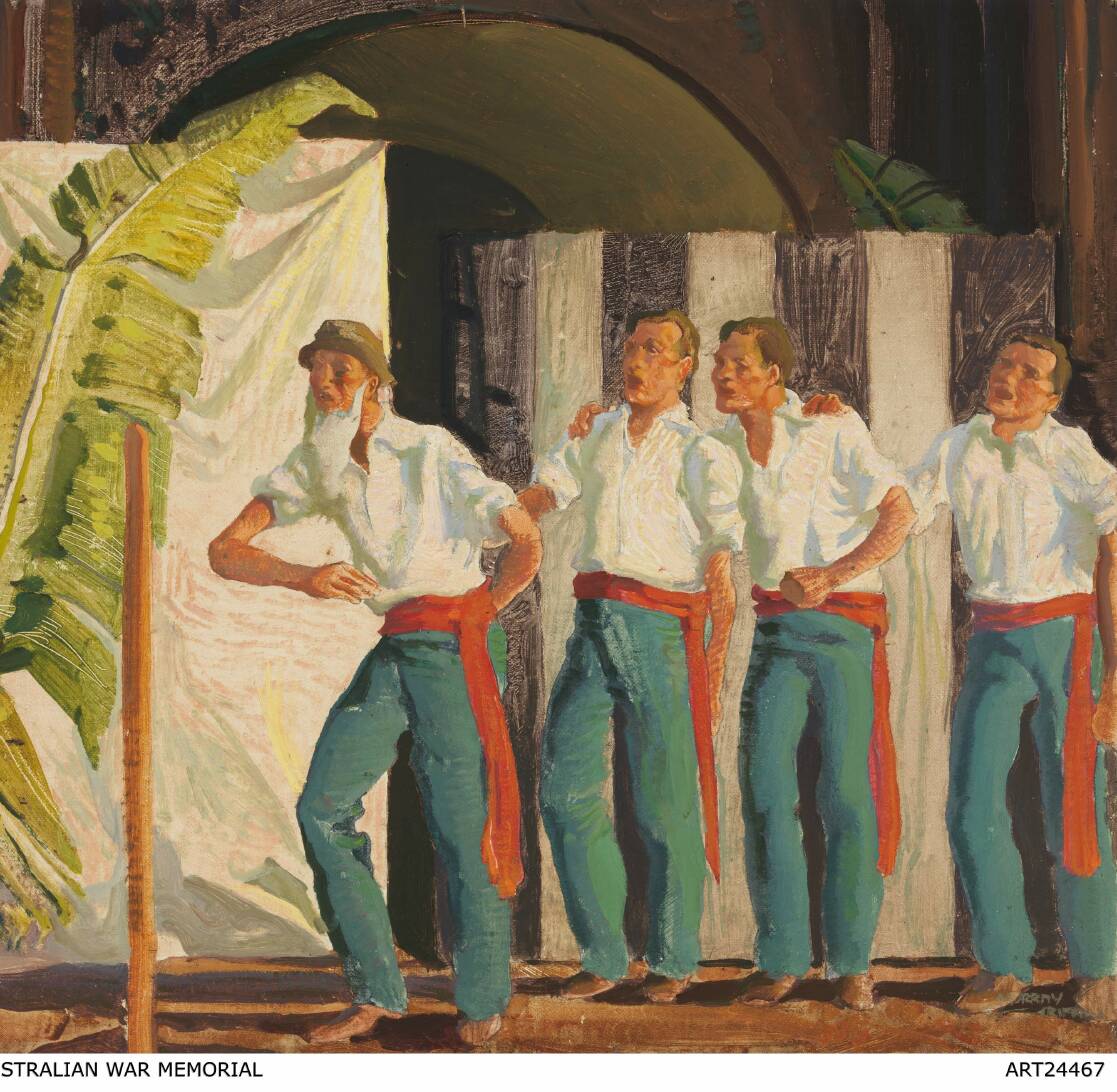

One-third of these songs were written for a female impersonator who sang about the topic of love.

"All of these songs are all about love because that's the one thing that I can't get access to," Latham says.

"The most popular person in a prisoner of war camp is a female impersonator. And it's not about sex, it's actually quite chaste. It's about how they just wished to be loved by a woman.

"One of the most important things for them was that they needed an object that they could love and feel love from. And these songs are really unusually beautiful, but they love songs for men dressed as women to sing to men."

In a way these songs - and the songs that were sung in other prisoner of war camps - were a form of self-care in a time long before conversations around mental health and well-being were the norm.

They recognised that the music was a way to keep the prisoners' spirits up, helping to endure and survive their captivity through illness, hunger and despair. They were these temporary moments of escape. As members of the Changi Concert Party themselves said, "we only worried when they stopped laughing".

So it's no wonder that prisoners wanted to keep a little piece of this escape after they left Changi. Proof that there was some light in their lives.

The Changi Songbook was priceless to them, which is part of the reason why it's so unknown. They loved the book so much that they didn't want to sell it or part with it in any way. There is however, a recording of some of the original members playing a selection of the songs.

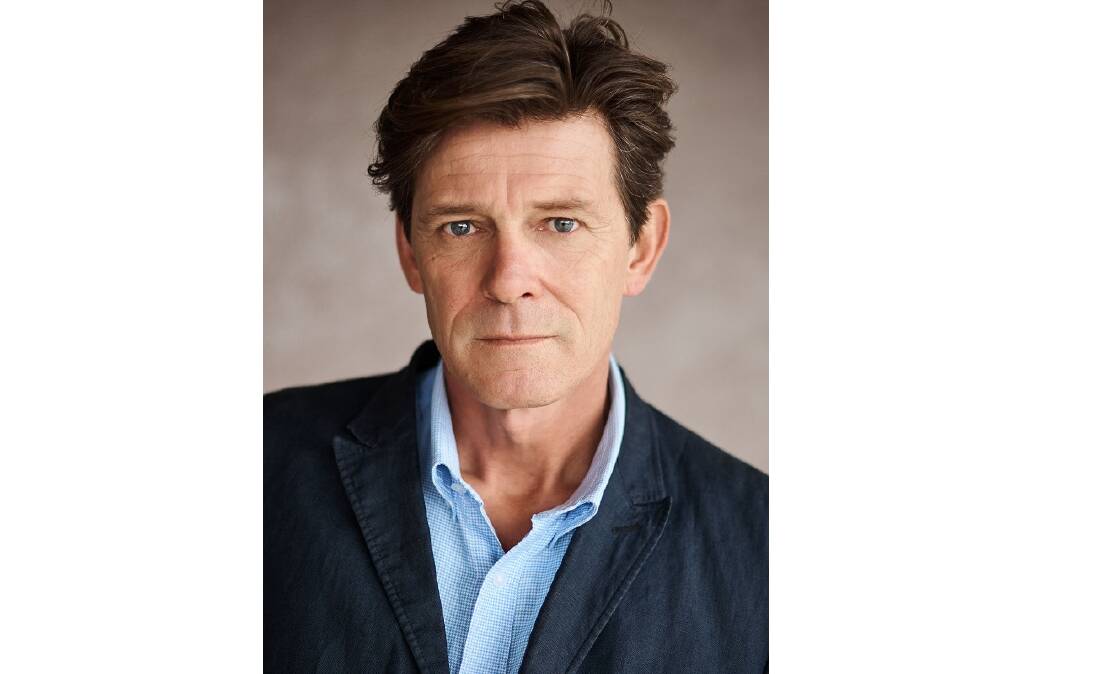

In a project funded by Australian actor Neil Pigot in the early 1990s, he organised for the remaining musicians to record their music after stumbling upon the story while working on A Bright and Crimson Flower - a theatrical retelling of the lives of Australian prisoners of war.

"What I didn't understand was I had a very conventional view of the Australian POW experience, which I think most people had have - and a lot of people still do - which was that they were captured, and they were tortured, and they were stabbed, and then they got out," Pigot says.

"But what that production gave me was an insight into the complex and nuanced nature of the society. They were cut off from the outside world and they created this extraordinary, complex self supporting society, within the camps. And an integral part of that were the concert parties."

On opening night, Slim De Grey, one of the original members and songwriter for the Changi Concert Party, was the audience. It was then that Pigot learnt that there had never been any recordings.

"The overwhelming propaganda that was here in Australia (after the war) was that the Japanese were evil," Pigot says.

"But when the guys came back and they were asked what happened and they told people about these concert parties, people would tell them 'No, that's not what happened. This is what happened'. Because the wartime propaganda was so pervasive, that when people were confronted by ex-POWs who wanted to tell exactly what happened, people would say, 'No, that's not true'. And as a consequence, a lot of them just shut up.

"So when we made the album in '93, it was clear to me that they were just pleased to actually make the album and have that story recognised."

The Women's Vocal Orchestra

From 1943 to 1944, in a Sumatran prisoner of war camp, two women, Margaret Dryburgh and Norah Chambers, started a Women's Vocal Orchestra as a way of transporting the prisoners through music. Life in the camp was one that saw cuts to their already woeful food rations, and malaria and dysentery were running rife.

Having already lived in a separate camp, where singalongs backed by a piano, were used to boost morale, they knew the power music could have. However, the move from one camp to another, meant they were left without the piano. So Chambers came up with the idea of a vocal orchestra, and Dryburgh began condensing complex works, changing their harmonics and making them suitable for a women's choir - with two alto parts and two soprano parts.

One of the things that Latham wants to acknowledge during the upcoming POW Requiem is just how amazing this feat in itself was. This task not only saw Dryburgh transcribe these well-known works from memory, but she did so and translated them perfectly, without any errors - because paper was scarce in camp there was no room for mistakes.

"The people who can do what she did have got names like Mozart," Latham says.

"They're super transcendent geniuses. I think she was really unusual and she just got forgotten."

A concert was planned for December 27, 1943 to mark their second Christmas in captivity. The orchestra was made up of women from different nationalities, speaking different languages, who became united as the music they learned together helped to break down barriers.

When you think of choirs, or singing in general, you think of the lyrics and then perhaps the notes that go along with it. But this choir was mimicking music created by instruments - the ultimate a capella group - so it didn't matter that they had people who spoke different languages performing to a group of women who also didn't speak the same language. It transcended language in that sense.

"They're the most beautiful pieces they could remember because they were just trying to reconnect with humanity," Latham says.

During the Women's Vocal Orchestra's first concert, the arrival of several guards was expected to disrupt the performance. However rather than calling a halt to proceedings, they elected to stay and listen instead. It was a quiet, carry on from those who had them working as forced labourers and it gave them confidence to repeat the concert in its entirety a few days later on New Year's Day.

However, after the third concert on June 17, 1944, the orchestra did not perform again. As the women and children entered their final year of captivity and endured two dreadful journeys to new and even more insanitary camps, many of them finally succumbed to malnutrition and disease. While Norah Chambers survived the war, Margaret Dryburgh died in April 1945, shortly after their arrival at their final camp.

Despite this sad ending soprano Susannah Lawergren - who will perform during the POW Requiem - can't help but see the hope in the works.

"According to the accounts, it renewed their sense of human dignity and made them feel like they could be stronger than what their situation was," she says.

"It is hard to imagine the women learning all these notes, painstakingly written down from memory, and finding the energy to sing them together - unable to stand, having to take another shallow breath every few seconds, in severe physical discomfort, weighed down with worry and hopelessness, but still finding the determination together to rise up against the dreadfulness of camp life and sing. It's extraordinary."

The POW Requiem is at Llewellyn Hall on October 29 at 1pm. Tickets from Ticketek.

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.