In a departure from the well-trodden tourist panoramas, photographer Mikko Takkunen's latest book, Hong Kong, unveils a Hong Kong bathed in a new light. Imagine towering skyscrapers not as imposing steel and glass giants, but as vibrant backdrops touched by the golden hues of the midday sun.

Takkunen draws inspiration from the masters of mid-century street photography, with echoes of Saul Leiter's evocative use of color and light. However, this is not a mere homage – Takkunen injects his own distinctive and contemporary voice.

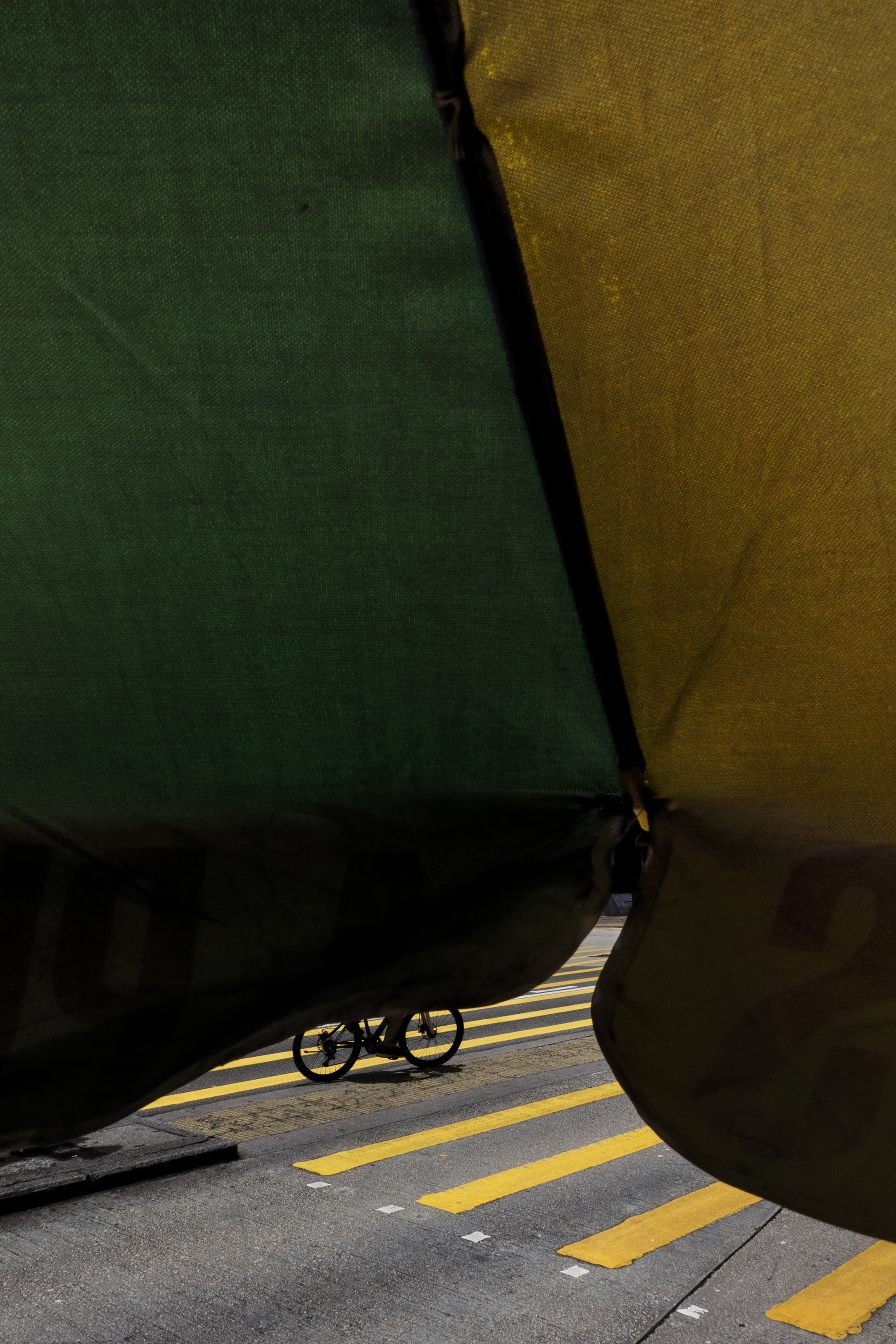

His lens forgoes the familiar landmarks, instead leading us on a captivating journey through Hong Kong's labyrinthine side streets and unbeaten paths. By capturing the exquisite details and quiet scenes often overlooked by the hustle and bustle of city life, Takkunen provides a peak through the cracks into the still beauty of the region, and in turn, its people. Hong Kong is a captivating portrait of the country, one that celebrates both its grandeur and its hidden gems, all captured with a fresh and innovative perspective.

In this interview I sit down with Mikko Takkunen and discuss his first major body of work, ahead of the release of his monograph Hong Kong, published by Kehrer.

How did you first come to photography? What was your entryway?

My first entry was while I was studying international relations. I'm from a very small town in the southeast of Finland and I always wanted to get away, so I ended up studying politics and international relations in Aberdeen, Scotland. I had been active in some of the NGOs and activist groups and I guess I was out to save the world. I thought that by studying international relations I would end up working for the UN or some sort of NGO.

It was during that time in Aberdeen when I would be hiking in the highlands with my friends that I started taking photos. Just of my friends and nature, but it soon became very much a passion and I was taking photos all the time. You know at parties there was always a camera around my neck.

It wasn't until one of my friends showed me the documentary film War Photographer by James Nachtwey that I learned about a thing called photojournalism. I felt like it combined my two big interests at the time – international relations and photography.

What happened next?

When I graduated from Aberdeen in 2006 I enrolled at the very last minute through the clearing process to study photojournalism in Swansea, Wales, which I started just a couple of months after Aberdeen. It was only there that I started to learn about the history of photography and the history of photojournalism.

I then worked for two and a half years as a press photographer for the Scandinavian media in London, until I heard about this opportunity to move to the editing side. I applied for it and I got it. So in 2013, I sold my cameras and started editing and that's what I've been doing as my day job ever since.

So you sold your cameras in 2013 – why was that and what made you buy them again?

The reason I ended up selling them was mainly because I didn't want to be perceived as trying to play for both teams as a photo editor and a photographer. I felt as though editors and photographers would feel like I was trying to compete in some way.

I was still taking photos with my phone just like everybody else, but it wasn't until around 2018 when my wife bought me a digital rangefinder camera that I started taking photos with a proper camera again – but still only occasionally on holidays or with family.

At the end of 2019, when I was based in Hong Kong, I was told that The New York Times, my current employer was going to transfer me back to New York. The realization that we were going to leave Hong Kong, the place where our first child had been born the year prior, and a place we really had learned to love, somehow made me want to start taking serious photographs of the city.

So it was the sense of leaving Hong Kong that drew you to want to capture it?

Yes, initially. There was the aspect that we were leaving and I didn't know if we would ever return, but it was also right at the end of 2019 which had been very tumultuous in Hong Kong, with massive street protests that lasted through 2019 to early 2020. There were street protests and barricades all over the city daily, often in our neighborhood, so it was right after that time.

Then in 2020, the mainland government issued this kind of national security law, which stifled freedom of speech in Hong Kong. So you could kind of also feel that Hong Kong was changing.

So the fact that I knew I was leaving, and the fact that I felt like Hong Kong was changing in many ways. The New York Times decided in the summer of 2020 to move its Asia headquarters from Hong Kong to Seoul, as a result of some of those changes – and then on top of that from the beginning of 2020, we had the pandemic.

The pandemic hit and my transfer to New York was delayed by 18 months because we weren't allowed to leave Hong Kong or allowed to enter the US. In the end, the fact that it took 18 months was very much a lucky strike for me because it made me decide – I want to make a book.

How did you adapt your shooting to the pandemic?

So I started taking photos in early 2020, during my tram rides to work and back, but then in March 2020 we were sent home to work remotely. I spent the first days working from home and I wouldn't leave the apartment for three or four days at a time. We were on the 19th floor of a fairly tall apartment building, and wanting to continue the work, I started taking photos from our bedroom and living room window.

I continued the photography I started, and when restrictions lifted I started going out at night. Then I would roam the streets for days on my own and it was a lovely time because I would jump on a ferry or tram and walk thousands of steps a day, so it was a special time without knowing how long I had left in Hong Kong.

A period of uncertainty for sure!

Very much so, yeah!

Did you look to symbolize this in the images?

Well, something that I was grappling with a lot and I'm still grappling with is – what are my photographs about? Because I come from very much a photojournalism tradition and at work, many of the images are very obviously about something, whether it's the war in Ukraine or Israel and Gaza, but with my photography less so.

During my time in Hong Kong, I fell hard into researching mid-century New York street photography with photographers like Saul Leiter and Ernst Haas – one of my favorites. If you know about Haas' famous Life Magazine essay, which was the first color essay published in Life Magazine, called 'Images of a Magic City', it was revolutionary.

It ran over two covers and it was these very striking images of New York, which weren't necessarily about something, there were just like colors and shapes and structures and so on. I think it was in this tradition, that kind of photography, that I wanted to capture Hong Kong, to present it in a new way.

So what were you looking for when creating the images? Did you have a point of departure?

I'm trying to make slightly different pictures, of anything that caught my eye. I liberated myself from having to have a meaning, like if I take a photograph of this thing because I like it, do I have to be able to say what it is about? I don't think so, although the photojournalist in me is still grappling with that.

When you look at the book there are no captions or precise locations or dates and I wanted the whole of the series that I put in the book to work as a whole and leave it to the reader in a way to get their sense of it.

I'm not afraid of trying to capture beauty, but I would want it to be a surprising beauty. I have one particular image that I shot of a street restaurant on a neighborhood street where it's a kitchen still life, there's a bucket and bright primary colors. I just thought it was such a beautiful scene, the image is an appreciation of that.

If you choose, you can also read something into it. You can see it's a very basic restaurant, it's not your Michelin kitchen, so you can always see beyond the obvious, but I was taking that particular image because of the beautiful light and the color that caught my eye.

When I was making the edit, I had specific thoughts in my mind. I tried to build the edit as a journey through Hong Kong, but what I call an off-beat journey. I don't have pictures from the peak or the hiking trails, there are certainly some more obvious Hong Kong symbols too, but they are my impressions of Hong Kong.

To notice these quiet scenes takes a lot of observation in the present moment. Is this a way you have always worked?

I have two kids and a day job so I don't get to go out with the camera as often as I would like to, but when I go I feel like I'm like a bull out of a gate in a rodeo, super excited. Especially those first few minutes or first half hour with the excitement of being out in the street – everything is interesting!

It depends on light, too. In Hong Kong, I was always seeking very sunny or very hard light. I would often shoot through the middle of the day, the time that photographers often try to avoid, just because the light is so hard and the shadows so dark. There are images from Central where you get very deep shadows because of the skyscrapers that you wouldn't get at any other time of the day.

You are a very successful photo editor for The New York Times. How did this experience inform your photography approach?

I spend my day job looking at images, but it's a very different kind of photography than what I do myself. But I would say it mostly informed me in the actual editing process. First of all, I've noticed that a lot of photographers are not great editors of their work and I was questioning when I was trying to put my work together, should I do it myself or should I leave it to somebody else? I had a vision of how the work would flow and the images should be included, so I felt I should try and do it myself.

The only person that I showed it to was my wife, who is also a photographer and a photo editor. She picked up 13 images from my edit that she said should be removed, and I took out 12 of those. I did it grudgingly as I didn't first agree with her, but when I considered it, I knew she was right, and the book was better.

When did you realize that the work would become a book?

About half a year into it I realized that it's not just going to involve me taking photos of home but this is something bigger. I started posting on Instagram, but I also felt like there was some project here, and at this point, I had very much gotten into photo books, it's my favorite form of looking at photography. So the last year of the project, and of my time in Hong Kong, I was thinking that this is going to be a book.

Did this change your way of shooting?

What was important to me is that there are certain photography books where I love the work, but like some collection books, they can be all over the place with no flow. I knew Hong Kong would not be the 'best images of Hong Kong' kind of book, but a whole concise body of work that took the viewer on a journey.

There are images that I love from my Hong Kong pictures that didn't make it because either they were too similar to what was already included or they didn't belong to the edit. I don't necessarily think that these are the best 68 images – I mean I certainly want the very best to be included – but overall it's 68 images that work together to make the whole.

Most of the images in Hong Kong are shot in portrait orientation. Is there a reason for this?

There were photographers like Saul Leiter and Ernst Haas that I noticed shot a lot of verticals and then I started trying it out myself. I then started seeing the world that way and it just worked. Hong Kong is a very dense and claustrophobic place in some ways and a very vertical city, so shooting in portrait emphasizes that.

I also find that it's easy to isolate subjects shooting vertically. On the street, if you shoot in landscape / horizontally then you tend to get more people in the scene; shooting vertically makes it easier to isolate the subject.

I would be remiss if I didn't ask about your photography equipment. What did you shoot with? And how did your choice of camera and lenses help you capture your vision?

I shot with four cameras, but ninety percent was shot with a Sony RX100 VII – a small compact camera with a 24-200mm equivalent telephoto zoom lens. As it's a fixed zoom you can't get wide apertures, but most of the time I shoot with a large F-stop like f/8 or f/11.

I also shot with a Sony HX90, which is even smaller and compact but it has an insane 24-720mm equivalent lens, which I used to capture images from the 19th-floor window onto the lower rooftop streets below. I could get close to people mostly using around 400mm or so, but I didn't only shoot on a telephoto – there are photos from the street that were shot at 80, 28, 35, and 50mm.

What I like about the Sony cameras is they're tiny – and I even started buying my clothing based on if the pockets would fit them so I could have them with me all the time. The telephoto capabilities also helped to compress the scene and helped depict a sense of density and claustrophobia.

I also used a Fujifilm X100F, the camera that my wife got me in 2018, which was my first proper camera after many years of shooting with my phone. Then there are two images in the book that were taken with my iPhone 11 Pro, including the back cover of the yellow door. It's quite incredible the back cover holds the quality and I don't think you would be able to know that it's an iPhone image.

The book has a fantastic introduction in the form of an essay by Geoff Dyer. Could you tell us a little about your collaboration with him?

I was honored to get Geoff Dyer to write the accompanying essay, I love his photography writing. What I love about him is that he doesn't necessarily try to intellectualize or interpret photographs, he writes what he feels. He was my dream writer for my book. Even when pitching the book to publishers, I said I would like Geoff Dyer to write for it, which at that point I had never been in touch with him.

I managed to hunt down his email address and sent him the book and to my surprise, he wrote back to me and said he was willing to write for the book. I was honored to have somebody so respected as a photography writer write about my work and share what kind of thoughts came to his mind when he looked at my work, and what kind of references he saw there.

Just like Robert Frank's The Americans has the famous Jack Kerouac essay in it, I'm not going to compare myself to Robert Frank, but Geoff Dyer is my Kerouac. I loved what he wrote. I told him to write what he wanted and I couldn't be happier. I'm also excited to hear what people think about his essay.

What do you hope people will take away from this project?

I hope that the images will bring enjoyment. By that, I mean a visual pleasure, but also a certain nostalgia for Hong Kong for those who have lived there or are familiar with Hong Kong. I'm definitely not trying to make any political or sociological statement here, it's more like my kind of a creative statement.

I'm very much a countryside boy from a small town and all my life I've had this fascination with big cities. I've had the fortune to live in London, New York, and Hong Kong, but in some way, Hong Kong feels to me like the ultimate metropolis and this is my love letter to that. I hope that it will bring joy to people.

What's next? Is there a current project you are working on? And what will you take from your experience making Hong Kong?

Before I came back to New York, I had all the influences of street photographers from New York so I was excited to see what work I could make in the same city as my heroes. So as soon as I got here, in my free time, I started shooting. I don't have as much free time as in Hong Kong, but I go out once or twice a month for a couple of hours – and that's pretty much what I have.

I have a pretty good set of images of New York already, but I do want to shoot further. I am hoping to make a sort of trilogy of cities; I would like to do New York next and then, I don't know why, but LA has always been this kind of mythical city to me.

The New York work is very much in the same vein as the Hong Kong work, but there may be even fewer people and more abstract details, going even tighter than in the Hong Kong work. Whenever I have a chance, I'm eager to get on the streets and keep working on it.

I have not seen Hong Kong depicted with such a serene and dignified approach since the photographs by Fan Ho. Takkunen's observations of the city take us on a collective journey through exceptional compositional technique and color theory and leave us with as many questions as we have answers.

It was such a pleasure to get to sit down and discuss Hong Kong with Mikko, and the added insights into his approach, equipment, and intentions bring an added dimension to the already stellar work.

Street photography is a term that is often used casually in today's world. However, not all images taken in this genre are created with sufficient thought and consideration of the subject. If you are someone who yearns for the classic street photographers of yesteryear, then Mikko Takkunen's Hong Kong is for you. I highly anticipate it to be one of the best street photography books released this year, it's a photography gem!

Hong Kong by Mikko Takkunen is published by Kehrer and is available now via the links below for $45 / £38 (Australian pricing to be confirmed).

You may also be interested in our guides to the best coffee table books, the best books for street photography, and the best books on portrait photography.