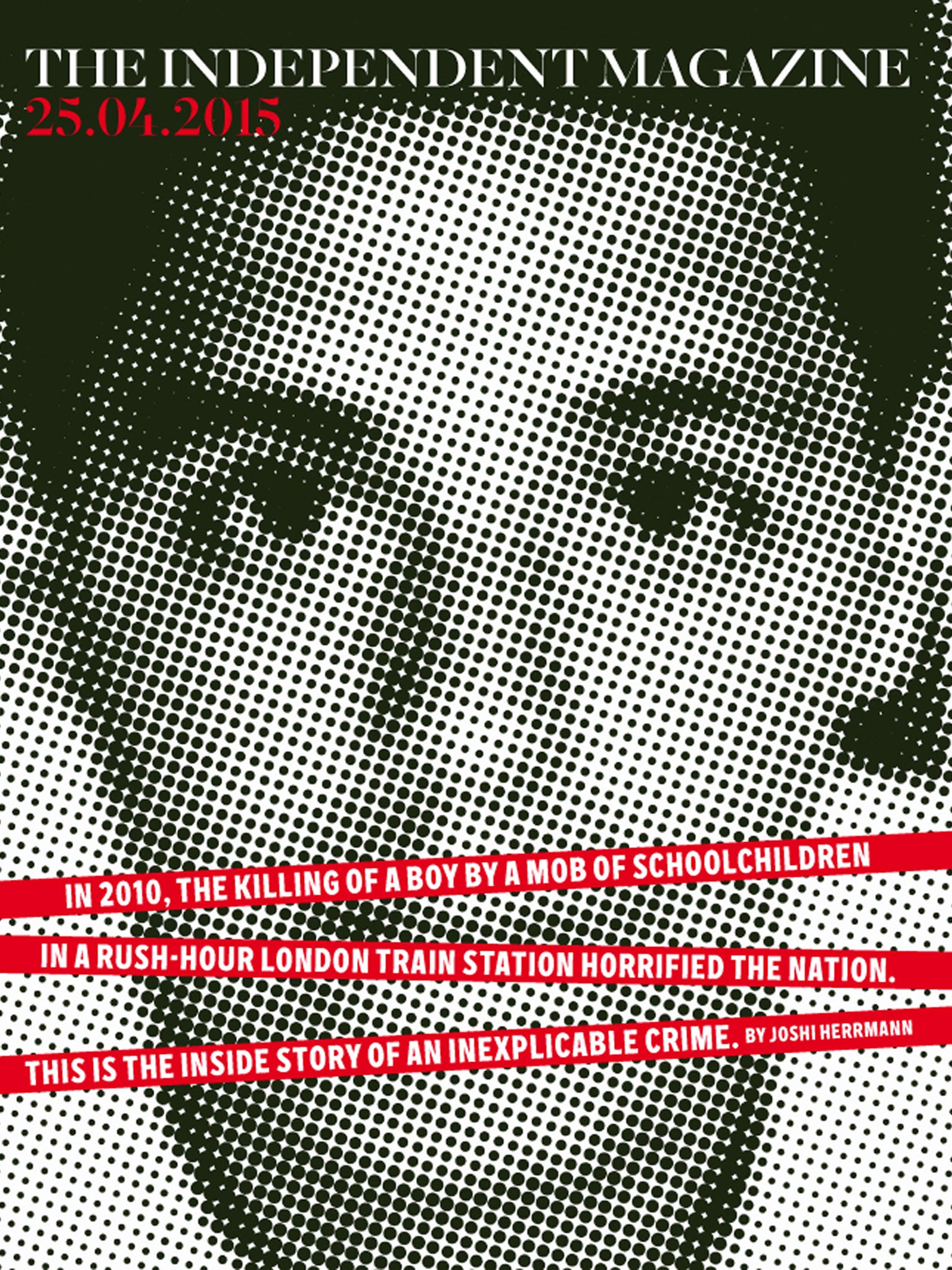

This article was originally published in 2015.

On the day they killed him, Sofyen Belamouadden got up at seven and went into his mother's bedroom to get his socks from a drawer the family shared. "Mum, I'm going now," he said, before catching the bus. Sofyen, who was 15, lived with his brother and two sisters in Acton, west London, and went to Henry Compton School in Fulham, a trip that involved two bus rides.

At noon that day, 25 March 2010, two months before the general election, he called his mother, Naima, to say he felt sick and wanted to come home. She told him to stay for a few more hours and phone again if he still felt bad. He said OK, and didn't call back.

After school finished at 3.15pm, she called to ask where he was. "I'm on my way home," he said, so she closed her clothes shop and headed home to make him tea. Sofyen's younger sister, Sumayya, then 12, who went to a school nearby, met him at the bus stop, but he told her to go on ahead. When his bus got to Shepherd's Bush, where he had to change, he received a call from a friend. Then, instead of getting a bus to Acton, he took the 49 in the opposite direction to Victoria station, somewhere he had no cause to go. Just before it arrived there, at about five, his brother Mohamed called to ask where Sofyen was. "I'm on my way home now," he lied, "I'm coming." Within about half an hour, he was dead.

What took place in the minutes that followed led to the largest murder investigation in the history of the Metropolitan Police. It resulted in 20 teenagers being charged with murder, the most ever charged over a single killing in Britain, and five trials lasting almost two years.

David Cameron, then weeks from Downing Street, made the murder the centrepiece of a speech about Britain's "broken society". "Just think about that," he said. "It was about 20 past five in the afternoon, when people were making their way home, thinking about where they'd go out that night or what they'd have for dinner, when a boy lay bleeding and dying on the floor of the busy station.

It is a confounding case. Not because the facts are disputed, but, as I've wondered for years – particularly when passing through Victoria on my commute – because of why it happened. How did a bunch of A-level kids, with good prospects and barely a criminal conviction between them, finish their school day by slaying a boy most of them had never met, in one of the busiest stations in the country? Sir Keir Starmer, then Director of Public Prosecutions, told me he hadn't come across another case like this during his five years in the role.

It was two and a half years later – October 2012 – when I first contacted Naima to ask if she would give an interview about her son's death. She agreed, and we set a time to meet, but she decided that it was still too painful to discuss. In July 2013, I contacted her again and she agreed to meet, but again she decided against it. Another year passed. Then, in October last year, Naima emailed me out of the blue. "You wanted to do an article about him, well I am ready now."

When we finally meet, it is in her living room, where she has changed the sofa because the old one reminded her of Sofyen sitting on it. "Sorry it took so long," she says, as I sit down.

The daughter of Moroccan immigrants who arrived in the Seventies, Naima is Muslim and wears a full veil, so only her eyes are visible. She says that during Ramadan, Sofyen would go to mosque every night, and during the rest of the year he prayed at home. He was close to his father, Abdeslam, a mechanic, who divorced Naima in 2002. Known as "Sof", he was a shy boy, "easily embarrassed," says Naima. She says he was always laughing, and if anybody was in trouble, he would help. "He was funny, happy, he enjoyed school, he enjoyed football, and he wanted to be a pilot," she says. A tall, athletic centre-back, he captained the Chelsea Kicks under-16s team. After his death, many of Sofyen's teammates, some of them promising players, stopped playing, according to a friend. "Many of us couldn't do football any more as we would keep thinking about Sof," he said. The friend describes Sofyen as having "strong morals" and says that he "looked after all of his friends". But he didn't want to be named, because "there is still beef" about his death.

He didn't expand on that remark, but underneath a couple of YouTube tribute videos, you can see what he means – hearsay about what kind of company Sofyen might have been keeping, though all of it is disputed by those close to him. Lawyers representing his attackers contended in court that the people who Sofyen went to join at Victoria that afternoon constituted a street gang called GFL, "Gangsters for Life", or "Guns for Life". Naima is sure Sofyen had nothing to do with gangs.

Eight of the group who killed him are thought to be still behind bars. Of the nine others who went to prison, most have heard that I wanted to speak to them, one way or another. Eventually, last year, one agreed to meet me at my local curry house, on the condition that he would not be named. So let's call him Jay.

On the morning of the murder, Jay says that something was in the air at his school, St Charles College in Ladbroke Grove, west London. There had been a scuffle with some kids from schools in west London – including Sofyen's – the evening before at Victoria, resulting in a bloody nose for one of Jay's friends, and there were rumours that the same kids might come back for more. "Some people were taking it seriously, some people were taking it with a pinch of salt. And if you don't know the people, you don't know how seriously to take the threat," he says. As the day went on, there were moments of tension: people saying "They're outside"; silent signals through glass panels in classroom doors that things might be about to kick off. Jay says that was "the theme of the day", but he wasn't nervous, and didn't expect the other group to come. By the end of school at 4.15pm, nothing had happened and everyone slowly made their way to the bus stop. "Then someone gets a call saying they're not coming to the college, they are going to be at Victoria."

Jay was in a good place. Despite coming from a poor household in a tough area of London, he was 16, had several As, Bs and Cs at GCSE, and was taking two of the hardest A-level subjects. Some of the friendship group he was with that day – black kids from south London doing their A-levels at St Charles – had even better results. Only one had previous convictions – for theft and cannabis possession. One was the son of a pastor. At the trials, the prosecution was unable to show that any of the group – referred to as the College Group – were members of gangs. Jay says he knew people who were in gangs, but this group weren't those kinds of kids. "There was no one who I would be scared to be alone with," as he puts it. Jenny Hopkins, who coordinated the cases at trial for the Crown Prosecution Service, came back to the group's good character several times when I met her last year. "To have 20 defendants who hadn't come into contact with the criminal justice system previously, and then for them to commit such a brazen and callous and brutal murder, in broad daylight, in Victoria station, is truly shocking," she said.

The back story to the murder is both confused and trivial. There had been an argument at a party, involving members of the College Group and one member of the group who Sofyen joined at Victoria (referred to in court as the West London Group).

The drama started where it would end – Victoria. The station's upstairs McDonald's was a daily routine for about 50 St Charles students who lived in south London, including Jay's friends – a place to hang out before everyone got their buses back to Stockwell, Brixton, Streatham and beyond. The day before the murder, the groups came into contact, resulting in one of the West Londoners punching one of Jay's friends. "It wasn't really a fight – just a few punches thrown," Jay says. Threats of repercussions followed.

Jay says he wasn't involved in the chat between his friends on Facebook and BlackBerry Messenger that night, probably because no one would have expected him to take a leading role in a fight. "It's not really my thing. I've always been popular but I'm quite a timid person, so I'm not fighting material." His only experience of violence before that week was a fight at primary school, and his only run-in with the law a caution for shoplifting. When the police trawled through the defendants' phone and internet histories, they found that some of Jay's friends seemed to be preparing themselves for another violent encounter. According to Hopkins: "You could see from the messages an intention to inflict really serious violence." At the sentencing appeal, the presiding judge, Lord Justice Leveson, said that it amounted to a "conspiracy to engage in an armed confrontation."

On the bus from St Charles to Victoria after school the next day, Jay says people had their headphones on and weren't talking. "It was subdued – it's normally loud and rowdy," he says. He didn't think the other group would have named a second location unless they were serious. "I started to think, maybe it's on." Jay was unarmed, but he says he knew that others were armed. "I heard that people had knives, but on that bus I wouldn't have been able to say, 'He has a knife, he has a knife'." He says it was unusual for his mates to carry knives, but he knew that "a lot of people do things for show", so it didn't overly concern him. "You can have a knife, but does that mean you are going to do anything?"

That question was about to be answered. Jay and his friends got off the 52 and walked to the western corner of Victoria's Terminus Place – the chaotic thoroughfare for buses and taxis in front of the station's main façade. By now there were about 30 or 40 kids in the College Group. Jay says he would only have recognised one of the West London Group, so he was relying on others to point them out. He didn't even know all of the group from his own college. He says people were on edge, but no one looked particularly aggressive. But then he goes on: "It's really hard, deep down, to know what people are feeling and thinking. Someone can appear as normal as possible, and do something totally crazy."

At about 5.25pm, with commuters streaming through the station, the West London Group came running from the other side of Terminus Place – the east side of Victoria, where the Apollo Theatre is. "They were walking towards us shouting, gesturing," says Jay. "I thought, shit." His mental image of the scene isn't clear now – but he didn't see weapons in their hands. "This is when it all kicked off. Someone [from our group] ran at them, apparently he had a samurai [sword], at the time I didn't see it." Four of his friends were now running at the opposing group. "I think they saw the samurai and thought, 'Forget this', and ran away. As they ran, more people from our group started to run, so I'm running now, towards them." What was he planning to do, punch someone? "Yeah. Or, I don't know, adrenalin took me, I don't know." He saw someone from his gang go for a knife out of a bag, or "what I now know is a knife."

He was running close to two others when they reached the fight's only contact point – at the top of the stairs which led down to the Underground ticket hall. Sofyen had tried to escape down the stairs but had been caught after tripping. "It was just a load of hoodies and jackets and scuffles and fighting," says Jay. He caught a glimpse of Sofyen "because of the colour of his skin" but didn't recognise him. Jay says it looked like one of his mates was grappling with Sofyen and they were tumbling down the stairs, trying to stabilise themselves on the handrails as they went. "And then people descended," says Jay. "Some people hesitated, and some people actually went down the stairs."

The court heard that Sofyen received at least one cutting injury at the top of the stairs. At the bottom, the eight who had descended punched him, stabbed him and kicked him in a frenzy of blows. The attack only lasted 12 seconds, but in that time Sofyen was stabbed nine times. One blow to his right shoulder went 12cm deep, slicing into his lung; two blows cut through his leg; one blow shattered a rib and wounded his heart; others hit major blood vessels. One of his attackers kicked Sofyen three times with what Leveson described as "horrifying ferocity" as he lay on the floor. The Crown would later use the spattered blood found on the suspects' clothes – meaning that it was airborne – to prove their proximity to the murder. When CCTV footage of the incident was shown during the first trial, Sofyen's father, Abdeslam, fled the court in tears.

"I got halfway down," says Jay. He sets out his decision to stop on the stairs purposely – it's probably the most consequential choice of his life. What he could and could not see from there, and – crucially – what he could not do from there, was the reason he was sitting with me having curry rather than in a prison cell. Jay says that from halfway down he couldn't fully see what was being done to Sofyen, apart from some legs, and the tableau of someone being beaten up.

When I pass those stairs on my way to work I think about the killing almost instinctively now. After meeting Jay, I stood halfway up the stairs and looked down to the spot where Sofyen was killed – and he's right, the view is cut off. Jay says he came to the spot himself when he got out of prison, because his girlfriend wanted to know what had happened.

Giving the ruling of the court at the sentencing appeal in May 2013, Lord Justice Leveson told the assembled families and journalists: "The account of this case should be told and repeated to young people everywhere: knives kill people and the effect of the madness of a few > hours – or of a moment – will ripple out and destroy or devastate many lives."

But five years after the murder of Sofyen Belamouadden, very few people know his name. The guys who work in the shop in the ticket hall which sells apples, samosas and cheap umbrellas inches from where Sofyen was killed know nothing about the crime. Neither does the woman in the tourist kitsch shop above the stairs, which displays post-box tea pots in the cabinet next to where Jay says he stood. According to Paul Cheston, the London Evening Standard's courts correspondent who covered the trials, the case got much less coverage than it warranted because of the many restrictions on reporting details of the teenage defendants.

But what are we supposed to remember? To the police officers who arrived on the scene, it looked like a classic gangland execution, albeit one delivered in a surprising setting, in front of hundreds of eyes. But soon the executioners turned out to be more surprising: a vicious killing carried out by innocents – successful inner-city kids of the kind who visit politicians in their dreams.

The questions that make the case perplexing to outsiders – and even insiders, like Starmer and Hopkins – gnaw at Naima, giving her pain a desperate, irresolvable quality. Several times during our interview, she breaks down in tears. "He went to Victoria and he died – how can I explain that to my children? How can I explain that to myself? For what reason? Nobody can tell me a reason he was stabbed. No one." Naima says she heard no answers at the handful of trial days she attended and, for her, time hasn't been the healer it is meant to be. "I can't believe it is five years. It's like yesterday for me. It's like every day of my life," she says.

Twenty of Jay's group were charged with Sofyen's murder under the principle of joint enterprise – the area of British law which allows defendants to be charged with offences they did not personally commit, if the prosecution can show that they took an active and willing part. It was used to jail Stephen Lawrence's killers, but the five trials that followed Sofyen's death were the biggest joint-enterprise murder prosecution ever brought to court in England and Wales, and provided a stark example of why some campaigners oppose it: the boy with the samurai sword, who unsuccessfully chased a different member of Sofyen's group, was jailed for murder, despite never having used it. In December, the Commons justice select committee called for an urgent review of joint-enterprise prosecutions, to prevent "over-charging".

The juries in the five trials largely rejected the Crown's case that the teenagers who chased Sofyen shared equal culpability – handing down three murder convictions, five for manslaughter, and convicting the nine others on lower charges such as GBH and violent disorder. Hopkins says she is "satisfied that it was right to bring the charges that we did." Starmer, who is set to become a Labour MP in London next month, says he "wouldn't stand in the way of a review" of the incredibly complicated rules on joint enterprise. "You can't go to a situation where unless you actually probably sunk the knife into the heart you're not guilty. I don't think anybody argues for that, but some greater clarity about the rules I think would be helpful," he told me. Jay, who was convicted of a lesser offence, had never heard of joint enterprise, and was stunned when, in the police station, they told him he was being charged with murder.

Jay and his group nevertheless received more than 130 years of jail time between them – sending the ripples of affected lives far, far wider than an ordinary murder. Naima was unhappy with the sentencing. "If these children were to get life for a life, then these stabbings wouldn't happen as often," she told me. Naima says she sees Sofyen's last dash in her mind, on an endless loop. Most of the family still receives counselling. One of them writes Sofyen's name obsessively on their body and paper, all day, and another one sleeps with a light on and sees visions of Sofyen's attackers everywhere.

Sofyen's killing – so appalling and happening so close to a general election – was read as a barometer of societal breakdown. Then shadow Home Secretary Chris Grayling said: "A country where schoolchildren kill each other in broad daylight on a rush-hour station is one where things are going badly wrong." The commentator Charles Moore said that it was "an extreme example of the powerlessness of modern society to deal with savage evil." Detective Chief Inspector John McFarlane, who led the inquiry, suggested on the phone in 2012 that Jay's friends seemed to be blurring the real world and the ones they inhabited online and in video games – which tallies with some of Jay's nonchalant descriptions of the day.

Naima remembers how well Cameron pronounced the family name in his speech. In it, he said big government had "drained the lifeblood of a strong society – personal and social responsibility."

Listening to Jay's description of events, this seems more like a crime born of the psychology of the playground in extremis – kids carrying out a murder for the same reasons they would want a certain pair of trainers or to commit a minor act of classroom vandalism: because everyone else is. I asked Jay if he thinks he had the option of not being involved. "Yeah," he said. "I mean, as I look back on it, I could have walked away, I could have took another route home. But the thing I've always said is: I find it hard to regret that, because you never expect someone to die. Feelings are sort of infectious. As soon as one person gets in the mood, it spreads to another person. Kids don't have the mental capacity of an adult, and a fight to a kid is completely different to a fight to an adult."

Yet, he still doesn't think he could have wielded a knife or kicked Sofyen on the floor as he lay bleeding. "It's a weird analogy, but it's like when you're drunk – the things you do when you're drunk are sort of not so unpredictable of you as a person, they are just an extension. There's sort of some logic to why you did it. So maybe somewhere deep down, there was that feeling that, yeah, we would. And maybe in me there wasn't."

As the bill comes and our interview draws to a close, Jay makes a remark that seems to go to the heart of things – a mental flip-around that speaks to the arbitrariness of a victim selected at random from a crowd, and that he says he tries to avoid thinking about because he finds it upsetting. I repeat a question I've asked all night: was Sofyen significant in any way? "I don't think anyone knew who he was," he says. And then: "The thing I've always thought is: he could have been me. He could have quite easily been the me of that other group. The one who doesn't fight – that's what his family says, and I can believe that, because if I would have died, it would have been the same and it would have been true. It would have been, 'Jay doesn't fight, Jay is quite timid, he just got caught'".