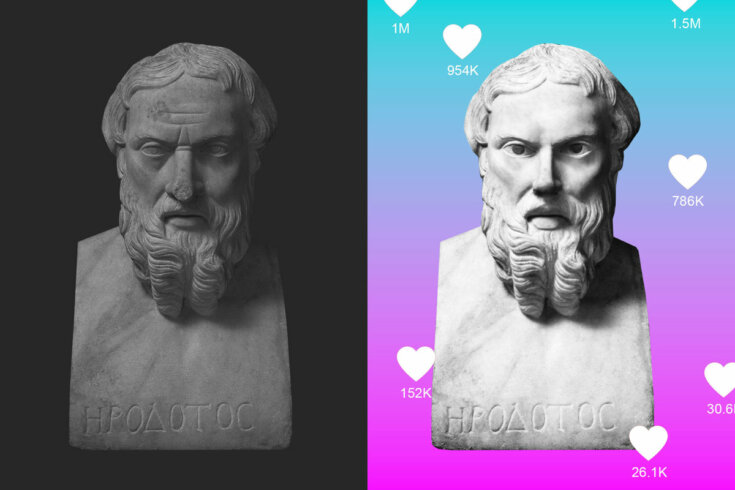

History is hot online. Videos labelled #history have collected over 135 billion views on TikTok. To give a sense of what this means, consider that videos tagged #taylorswift have been viewed around 175 billion times. Not bad for a subject a lot of people avoided in school.

Brevity is one reason. In just a minute or two, you can get a quick tour and history of the secret annex in which Anne Frank and her family hid from the Nazis. Or two minutes explaining how Roman aqueducts worked. Or maybe a series of quick then-versus-now photos from around the world. History online can also be info-taining. In just over thirty seconds, you can see restored footage from 1901, set to modern music, of kids seeing a camera for the first time. Or you can laugh at comedian creator Kyle Gordon’s purposefully sarcastic and over-the-top takes on historical periods. “A nice, tall glass of mercury! This’ll cure my hiccups in no time!” he shouts in a video about “life in the 1800s.”

Pithiness makes the subject matter more accessible, but ideally it can also prompt users to seek more information from more traditional sources. “I’m trying to work on putting more resources in my videos and explaining where I get my information from,” archeology content creator and PhD candidate Stephanie Black said in an interview in 2022. “The response I get from people is like, ‘Hey, I want to learn more!’”

But not everyone creating history content online has credentials like a PhD. “One of the challenges in the online ecosystem is that much of the information that we see is not labelled, it’s not sourced,” says Jason Steinhauer, founder of the History Communication Institute, an independent research organization based in Washington, DC, and author of History, Disrupted: How Social Media and the World Wide Web Have Changed the Past. “In theory, having historical information on the web can be a very good thing. In practice, it’s much more of a mixed bag,” he says.

That might be putting it mildly. While it’s not all bad, much of what content creators categorize as history on social media platforms is junk—pseudo history at best but often just wrong or total fiction. Even a cursory search for history content on a platform like TikTok reveals a whole host of examples of history being leveraged to make incredible claims seem credible. Plato’s description of the lost city of Atlantis as an island beyond the Strait of Gibraltar that was swallowed by the sea could be used to argue that the Richat Structure—a geologic dome in Northwest Africa—is the lost city’s original location. Or hieroglyphics might be willfully misinterpreted as evidence that ancient civilizations built temples and pyramids (and even spaceships) along designs given to them by aliens. If that sounds like a straight-up conspiracy theory, you’re not wrong. Deliberate misreadings of history are regularly used to lend weight to wild postulations.

Online factual distortions are likely to get worse as generative artificial intelligence becomes more sophisticated and easier to use. Already, last summer, users of the generative AI tool Midjourney created multiple images depicting events that never happened, like the “July 2012 Solar Superstorm & Blackout,” the “2001 Great Cascadia 9.1 Earthquake & Tsunami,” and people staging the moon landing. The photos were posted on a forum for people to discuss Midjourney’s capabilities. But images like these won’t always stay in a realm where they’re understood. As a Reddit user noted under one series of these fake photos: “People in 2025 are going to have a real difficult time with misinformation. People in 2100 won’t know which parts of history were real.” Especially if all they do is follow social media.

By its design, social media targets our emotions to prompt engagement. At the same time, we’ve been primed to assume that, despite these platforms being owned by data-hungry, manipulative, profit-seeking tech companies, social media is democratic. But social media isn’t democratic; it’s populist. It has always had an anti-expert bias—since long before Elon Musk took X (formerly Twitter) into overtly anti-establishment territory—making it fertile ground for grifters and posers. It’s a land of charlatans. Even Wikipedia, a standard go-to reference, was initially founded with an anti-expert ethos, Steinhauer points out.

This innate knee-jerk counterintuitive position that comes with being online can feel empowering, even flattering. We can easily convince ourselves (or be convinced) that we might actually know more than the experts. It’s also an addictive way to see the world. This makes it the perfect worldview for social media algorithms to leverage to keep us scrolling, our attention rapt.

What you get online, then, is a media space where deliberately (often ridiculously) counterintuitive interpretations thrive—where someone is always ready to tell you the “real” story that “they” (traditional sources of information and opinion, like mainstream media, politicians, academics, etc.) don’t want you to know. This kind of content “succeeds in becoming visible precisely because it purports to be telling you something that the experts never told you or being contrary to the thing that the experts believe,” says Steinhauer. “And that is what makes it very attractive and believable . . . it seems to be letting you in on a secret that has been withheld from you.”

In November, somewhere between TikTok and X, a handful of users and creators started posting about Osama bin Laden’s “Letter to the American People” from the early aughts. The letter, a wild-eyed and antisemitic screed, called American foreign policy imperialist and said that the oppression of Palestine had to be “revenged.” “I know bin laden was bad! i’m just saying he had some points about american hegemony,” one user on X noted in November when the letter resurfaced. “Replies incoming,” another responded. That is to say: here comes the attention.

“Subverting your expectations, the opposite of what you expect, something that surprises you, something that goes against the narrative of [what] the authorities have told you—that type of content all does really well” online, Steinhauer says. Like, for example, the idea that you actually gotta hand it to Osama bin Laden.

Amid the heated reactions to the Israel–Hamas war, the idea that bin Laden had valid criticisms about American foreign policy was enough to generate a wider discourse—even if it was just to re-denounce him. But did it do anything to help clarify our current reality? Did this recent history help inform our present? Or did it just get a few social media users lots of attention?

We deserve to know our past better in order to properly contextualize our present day, says Steinhauer. “I think we need to think really critically about whether this is the type of history that we want. Because when it comes to really complex issues like what’s happening in Israel and Gaza or like what’s happening in Ukraine and Russia, we deserve a more sophisticated, rigorous, nuanced understanding of the past,” he says. “And we don’t tend to get that on social media. What we get is a lot of people vying for visibility.”