What does the future of the British monarchy look like? The short answer to that question, as we look towards the arrival of King Charles III (it sounds so strange, doesn’t it?), is that it will have a ruddy red face, a combover and be extremely well tailored, albeit with a self-consciously fogeyish sense of style. It will, almost inevitably, be a time when the mettle of the man, those around him and the constitution he inherits will be tested, very possibly to the limit.

There’s no better way of summing it up than the cliche about Elizabeth II being “a hard act to follow”. The flipside of her extraordinarily long reign is that people have become so used to her, and any successor, even one as familiar as the Prince of Wales will look like a bit of an imposter. A different face on the banknotes, the coins and the stamps after so long, a different voice and face delivering the Christmas broadcast, a different cypher on the Royal Mail vans and police and military badges and regalia, all will feel a bit alien: “C III R” will take some getting used to. New words for the national anthem, too.

Some, perfectly fairly, will point out that no-one, not even parliament, is given the opportunity to vote for the head of state, and that the public will be getting Charles III whether they like it or not. That’s how the hereditary system works, and it will be questioned far more than it was, say, in February 1952 when deference was the norm. There will be a “moment” when the national trauma - and it will be nothing less than that at the passing of the last monarch - threatens to morph into a questioning of the way the institution works. This will be especially intense in the realms and territories where republican movements have become active again, and a change at the top is an obvious cue for reflection and reassessment in places such as Jamaica or Australia.

The Queen’s global reputation as an almost flawless monarch commanding the affection of the people goes before her, and anything the new King does will inevitably look inferior, even where it is not. Every decision, every utterance, every choice of word will, frankly, be weighed and parsed by the media and set against a sometimes idealised, not to say hypothetical, view of what his mother neither would have done or said. The media will kick him around a bit, in other words, as is their habit. Then again, he’s used to that.

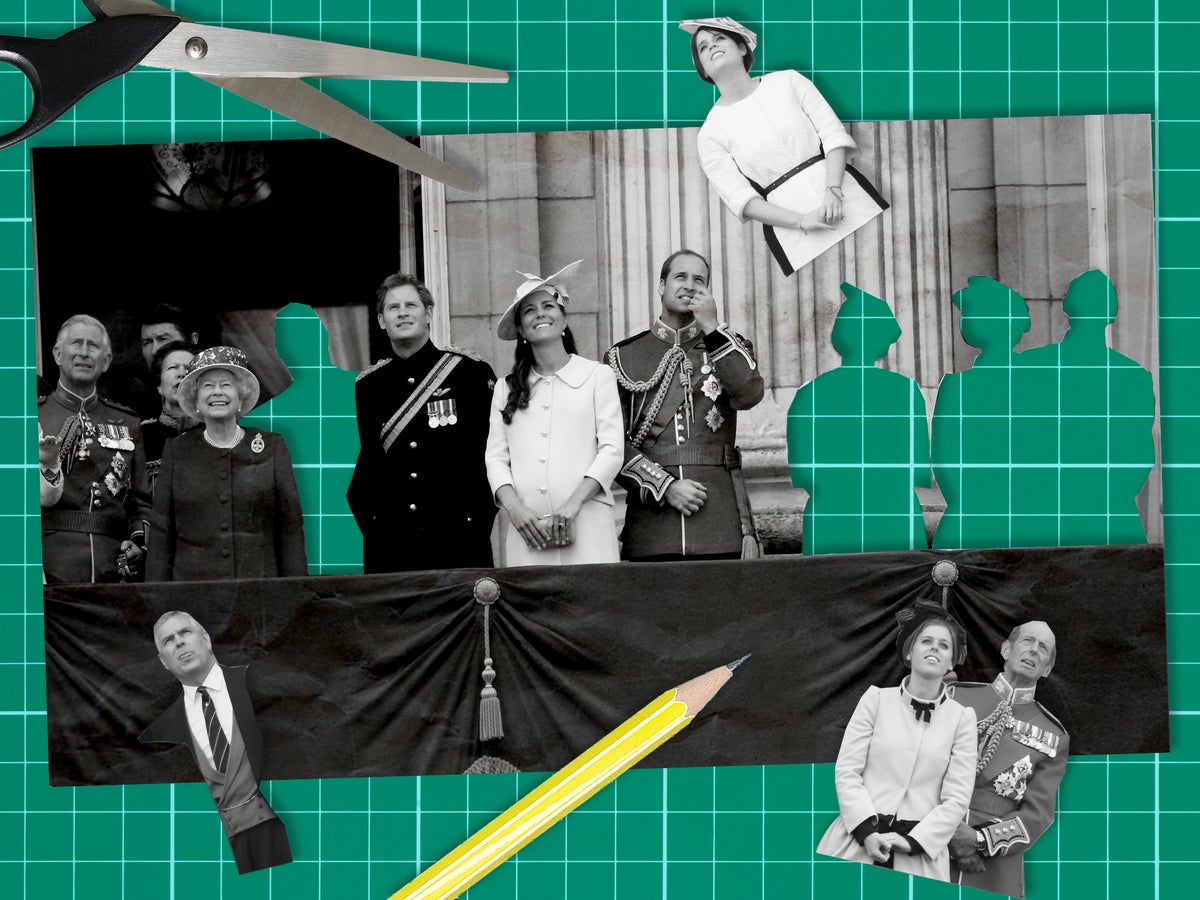

It’s obvious that Prince Andrew and his daughters and families will be pollarded

The first decision will be what his regnal name will be, because it is a tiger of choice. There’s a famous scene in The Crown when courtiers ask the young Queen what she would like to be called, and she answers proudly “Elizabeth of course”. Unlike some bits of the Netflix series, that must have some accuracy, for obvious reasons. But bear in mind her father, who was Prince Albert, Duke of York, chose the name George VI over his own to signify a sober continuity of the conventional ways of his father George V, in contrast to his elder brother Edward VIII, who had abdicated so shockingly. If he wanted to mark a change from his days as an outspoken Prince of Wales to becoming a dull, uncontroversial and conventional King, Charles might choose to style himself George VII. But, at 74 this November, it seems a little late for reinvention.

Next will be the coronation. There’s some suggestion that it will be done rapidly, almost to prevent any of his overseas realms ditching him before he’s even crowned, and to pre-empt any anti-Charles sentiment. The service will remain religious, but from wants known of the Prince’s express wish to be “Defender of Faith” rather than “Defender of the Faith” it’s going to be more inclusive and ecumenical in style. It will probably also be as slimmed down and shorter, as befitting a medium-sized European power rather than a global empire, as was still the case in 1953, a ceremony he attended as toddler. Fewer troops (unavoidable given our now relatively tiny army), a smaller entourage of his family, and slightly less elaborate robing can be expected.

There will also be intense interest in the status and role of the woman soon to be known as Queen Camilla, the first Queen consort since 1952. Prince William and Kate will be upgraded to Prince and Princess of Wales, and they can be hopeful that the people and leaders of Wales are content with the nomination of these English personalities to their symbolic role, feathers and all.

It’s obvious that Prince Andrew and his daughters and families, like a number of other Kents, Gloucesters and the more remote branches of the Windsor family tree will be pollarded, and with them their cost to royal budgets and any residual draw on the taxpayer. At a time when the cost of living crisis is savaging living standards, it would be a shrewd move for the new King to demonstrate a preparedness to share the squeeze, or at least not be seen to be self-indulgent. Many of the monarchy’s bad patches have been when hard-pressed public and sharp-eyed politicians are repelled by luxury and extravagance at their expense - as in the high-inflation 1970s and again in the early 1990s, when the Queen agreed to pay income tax for the first time. A display of costly opulence in a lavish coronation would be something to divide the country rather than unite it in the excitement of a new reign.

If he is wise, Charles will say as little as possible about anything outside the Overton Window of consensual views

And what will that reign be like? It will obviously be shorter than his mother’s (it would take quite the breakthrough in gene therapy for Charles III to see his Platinum Jubilee). If he is wise, Charles will say as little as possible about anything outside the Overton Window of consensual views. So climate change, Ukraine and general social cohesion are OK, but not trans rights or food banks, nor human rights in China and the Middle East. British monarchs haven’t led their troops into battle since the eighteenth century, and it would be unwise for this one to find himself suddenly in the middle of a culture war.

Assuming Boris Johnson survives that long, this prime minister is unlikely to be a natural ally or soulmate of Charles, but Charles will just have to endure the outrages, just as his mother had to put up with being advised unlawfully to prologue parliament in 2019. She was lied to, and so will her successor be, because Johnson, in my opinion, is at least content to deceive the highest and lowest in the land on an equal opportunities basis.

Charles’ most productive role, and an obvious one now, would be to mend some of Britain’s broken international relationships, not least with European nations. There have been instances before when a respected monarch is followed by one apparently ill-suited to the role. There’s a tempting comparison between the future Charles III and Edward VII, Queen Victoria’s son, for example. Like Charles, Edward was a Prince of Wales who allegedly carried on affairs, could be spoilt as well as charming, and spent long periods of a long apprenticeship despised by the public. Edward VII ascended the throne aged 59 (so a spring chicken by Charles’ standards), and took it upon himself to repair Britain’s then (as now) poisonous relationship with France. His personal diplomacy on an official visit to France did much to secure the Entente Cordiale and the historic alliance forged in 1904. In due course King Edward grew to be popular, and had a spud, a cigar and numerous hospitals and bridges named after him.

We could see Charles and Camilla setting out on similar missions, as well as repeating the Queen’s successful Irish visit in 2011, and to important new economic partners such as India and the Gulf states. That alone would justify their existence, and it’s a task beyond Johnson, so synonymous is he with Brexit.

So, smaller, cheaper, less flummery, more democratic and more reflective of modern Britain and the contemporary Commonwealth - both multicultural, multicultural communities - would seem to be the future role of the British monarchy. It will also need to work even harder than ever in its diplomatic, trade and charitable roles to continue to command the support of the public in hard times. The secret of the longevity of the British monarchy over its 1,000-plus year existence (give or take the brief King-less seventeenth century Commonwealth), is its ability to adapt to changing times and to do what the people and the politicians demand of it. There’s no reason why Charles shouldn’t manage that. Is there?