Finding a good partner in life is a tricky endeavour, so imagine how much more difficult this task becomes when you’re rooted in the ground.

For most land plants, the inability to move means they have to find clever ways of transporting fertile material to suitable mates. In the millions of years it took for land plants to evolve, they developed intricate and unique relationships with animals that have allowed them to successfully colonise almost every landmass on the planet.

Think of flowers luring in pollinators with the sweet scent of nectar, bristly seedpods travelling on the fur of passing animals, or seeds passing through the digestive tracts of birds and grazers to germinate in their poo.

These animal-plant interactions are often mutually beneficial, or “mutualistic”. The animal gets a reward in the form of fruit or nectar, while the plant gets to disperse its pollen or seeds over a much greater distance than it would have achieved alone.

Mutualism between plants and the animals that eat them was thought to be a unique adaptation to life on land. Underwater, movement from currents and buoyancy take care of the dispersal and fertilisation of seaweeds and marine plants. Seaweeds don’t need animals to spread their seed far and wide – or so it was thought.

Our new research challenges this assumption by showing examples of mutualism among seaweeds and animals. It adds to a growing body of evidence that suggests the ability to use animals to fertilise, and spread fertile material, may not be exclusive to land plants.

From spore to kelp

Last year, researchers at the Sorbonne University found that isopods (marine invertebrates about 2-4cm in length) can increase fertilisation success in the red seaweed Gracilaria.

As the isopods feed on small algae growing on the red seaweed, seaweed sperm attaches to their bodies. They then carry this sperm to female seaweeds, which can fertilise exposed eggs. In return, the isopods get a meal and protection from predators.

This year, our team found several examples of how much larger seaweeds have sex with the help of tiny animals.

Kelps are the largest seaweeds in our coastal environments. They provide habitat and shelter for many other species – but their reproduction has been somewhat of a mystery.

They have what is called a biphasic life cycle, where two separate living organisms alternate to complete the life cycle. The organisms that form their reproductive life stage are called gametophytes.

Gametophytes grow from spores released by adults. Male and female gametophytes make sperm and eggs, and when they fertilise they produce baby kelp that develop into adults.

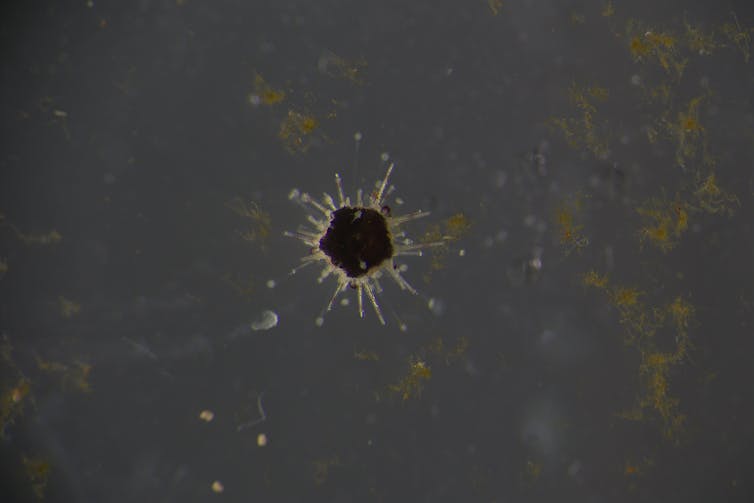

However, gametophytes are microscopic in size (about 0.5mm). Being this small, you might imagine finding another gametophyte to fertilise would require incredible luck. After all, the ocean is very large, and gametophytes need to be as close as 1mm to fertilise successfully.

It has been assumed gametophytes must exist in high densities in the ocean, and this is why successful fertilisation occurs.

Fertilisation through poo

Initially, our team was curious about whether tiny grazers would suppress fertilisation success in kelps by eating gametophytes.

Adult invertebrate grazers, such as snails and urchins, can drastically damage kelp forests. So we wanted to find out if juveniles played a similar role. To our surprise, we found the opposite.

Read more: Sea urchins have invaded Tasmania and Victoria, but we can’t work out what to do with them

For our research, we fed gametophytes to juveniles of two urchin species, Tripneustes gratilla and Centrostephanus rodgersii, as well as the micro-snail Anachis atkinsoni.

We found the gametophytes could survive through the grazers’ intestinal tracts. We kept the pooed-out gametophytes for a few weeks, and eventually noticed lots of baby kelps growing from the the poo of Tripneustes gratilla and Anachis atkinsoni. We’re not sure why there were no baby kelps growing from the poo of Centrostephanus rodgersii (a species that overgrazes kelps in Tasmania).

Moreover, none of the gametophytes kept outside of the poo were fertilised. This means being eaten by tiny critters, and ending up in their poo, is somehow beneficial for kelp sex.

We don’t know exactly why this is. We think it may be due to increased proximity of gametophytes through ingestion, or the effect of some chemical cue from the poo itself.

Where did animal-mediated reproduction begin?

Finding repeated examples of animal-mediated fertilisation in the ocean indicates this process might have originated underwater and not, as previously thought, on land.

In evolutionary terms, seaweeds are a lot older than land plants. So perhaps the unique relationship between animals and seaweed reproductive biology was passed on to land plants.

Alternatively, it could be animal-mediated fertilisation independently evolved multiple times throughout plant evolution, both on land and underwater.

In either case, our findings are changing the way we look at seaweed-herbivore interactions. Seaweed grazers often get a bad rap for causing devastating loss in kelp and seaweed habitats.

Here, we highlight a positive impact: a grazer-seaweed story with a happy ending! Small grazers may fulfil an important role in seaweed reproduction, by making sure microscopic gametophytes in the big ocean can find each other and make babies.

In the end, it’s all about sex! Seaweed sex, that is …

Read more: Can seaweed save the world? Well it can certainly help in many ways

Reina Veenhof receives funding from the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment.

Curtis Champion receives funding from the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. He works for NSW Department of Primary Industries.

Melinda Coleman receives funding from The Australian Research Council. She works for NSW Department of Primary Industries.

Symon Dworjanyn receives funding from The Australian Research Council. He works for Southern Cross University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.