Victorian England loved a juicy scandal and Zadie Smith situates The Fraud in one of the mid-19th century’s most toothsome cause célèbres: the Tichborne case.

Sir Roger Tichborne, heir to a title and fortune, went missing when the ship he was travelling on sank en route to Jamaica. His distraught mother, Lady Tichborne, clinging to the idea her son had been plucked from the ocean by a ship bound for Australia, advertised widely in the newspapers. In 1864 a man came forward claiming to be the lost heir.

Review: The Fraud – Zadie Smith (Hamish Hamilton)

To modern eyes, the question around the man who became known as the Tichborne Claimant, or simply the Claimant, is less about whether he was genuine than how anyone could possibly have bought into the deception.

The Claimant, a working-class butcher from Wagga Wagga, was obese. He spoke no French despite it being Roger Tichborne’s first language. He had no Greek, the cornerstone of a British upper-class education, and was barely literate.

Notwithstanding the obvious problems in his story, the Claimant came to England to litigate his right to the Tichborne inheritance, leading to two widely publicised court cases. He was ultimately revealed to be plain Arthur Orton born in Wapping, one of the poorest areas of London.

Throughout the hearings, the Claimant was supported by an ex-slave from Jamaica named Andrew “Black” Bogle, who had worked for his uncle and knew the young Roger well. The fraud at the centre of Smith’s novel – the Tichborne court cases – ensnares the reader in class prejudices and the brutal history of slavery in Jamaica.

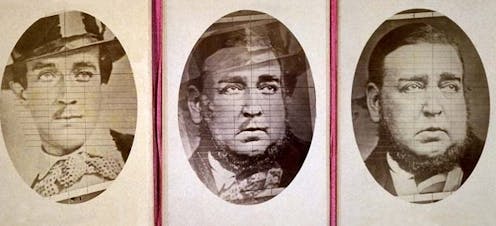

Smith conjures a carnivalesque mob of supporters around the Claimant who are devoted to a collection of causes: reform, working-class rights, freedom, anti-slavery and the strangely topical “No Vaccine For The Poor Man’s Child”. In this way she recreates the sideshow atmosphere of excitement and mania that gripped Britain and can still be seen in the illustrated newspapers of the time.

The odd alliances forged around the Tichborne case are reflected in the Victorian family Smith chooses to place at the centre of her novel, the household of Victorian novelist, William Harrison Ainsworth. Ainsworth moved in the same literary circles as Charles Dickens. But while Dickens remains one of the most significant writers of the period, Ainsworth’s novels, sometimes wildly popular in his lifetime, are now universally unread.

Sarah Ainsworth is a former servant, turned William’s second wife, who sees in the Claimant the oppression of the working man and woman. Eliza Touchet, William’s cousin, is dedicated to the cause of anti-slavery.

Also drawn from the historical record, Eliza was a clever woman whose wit enlivened Ainsworth’s literary dinners. In the novel she is brought into the family to support William’s first bride Frances while he is away.

Eliza finds herself placed between Frances and William in an unacknowledged ménage à trois characterised by true love on one side and sexual punishment on the other. As William’s bon vivant lifestyle grows, Frances withdraws and it is Eliza who sincerely mourns Frances’s youthful death of a broken heart.

Eliza honours Frances in her dedication to the cause they shared. But to Ainsworth’s daughters and his second wife, Sarah, Eliza is the stereotype of a dour Scots widow. Yet Sarah and Eliza form an unexpected collaboration. They begin attending court, sitting through months of sessions. Eliza develops a growing obsession with the ex-slave who claims to recognise the Claimant, Andrew Bogle.

Read more: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens: class prejudices, the convict stain and a corpse-bride

Victorian scandal

The Tichborne controversy sets up expectations for a novel about a conventional Victorian scandal. What is particularly interesting about scandal, according to sociologist Ari Adut, is not only the (often enjoyable) revelation of a disgraceful transgression, but the way it functions as a means of policing the social consciousness. It is

a ritual through which groups assert their core values and purify themselves by publicly marking certain individuals and behaviours as deviant.

Or as Oscar Wilde quipped, “[…] scandal is gossip made tedious by morality.”

By centring her story on Eliza and Andrew, Smith utilises a common narrative strategy of revaluing traditionally silenced subjects and critiquing and satirising Victorian ideas of gender, sexuality and empire.

But Smith goes much further, exploding any idea of teleological certainty. Nothing is simple. Complex notions of fraud, morality and deviance intertwine: almost everyone is a fraud, as is the book itself.

At 451 pages in length, The Fraud feels like the weighty, Victorian, three-volume novel it often taunts. Yet, there is a lot of white space. While there are 43 chapters, some are as brief as a paragraph, and very seldom do these extend past a couple of pages.

That Smith convinced her publishers to produce the book in this format speaks volumes about her power as a star writer. If Ainsworth’s rambling novels are comic – chapter 18 reproduces the first page of his (actual) The Tower of London, a single sentence of cascading, subordinate clauses, which show no sign of winding down to a full stop – then the idea that Smith’s novel is historical fiction is also an illusion.

The novel sets up meta-fictional questions about the value – and destructive capacity – of Victorian literature. Or perhaps literature in general.

Ainsworth’s narcissistic obsession with his own popularity and his next historical novel make clear his weakness of character and failures as a husband, lover and provider. These failures make him blithely disinterested in issues that threaten the comfortable myths on which the British Empire stands.

Killing Dickens

Eliza, aware of her own invisibility, serves and observes Ainsworth and his arrogantly self-satisfied dinner companions: Dickens, fellow writer William Makepeace Thackeray and the illustrator George Cruikshank. This seems to cast the white, male novelist as an easy target: dull, pompous and elitist frauds. And Smith, via Eliza, directs much of the novel’s humour towards the figure of Dickens (there is, after all, a lot to make fun of). Smith herself has written how cathartic it is to kill Dickens.

Yet Eliza also recognises Dickens does not fit the narrative she is telling. Dickens catches Eliza’s eye, he sees her. Eliza identifies Dickens’s interest in the poor as more powerful than the other novelists, calling it “vampiric”.

Similarly, the text itself is far closer to a fragmented Gothic narrative like Bram Stoker’s Dracula than generic historical fiction. And like a Gothic novel, whose purpose is to unsettle the reader, Smith’s book contorts its timelines. Smith kills off Dickens only to have him reappear, vampire-like, a couple of chapters later: the white, male author is not so easily displaced or dismissed.

Read more: Bram Stoker's Dracula: bats, garlic, disturbing sexualities and a declining empire

Eliza herself is, in many ways, the perfect protagonist of a Neo-Victorian novel: the silenced Victorian woman who seeks out the ex-slave. This extends to her sexual relationship with Frances, described poetically with a flowering of desire reminiscent of the writing of Sarah Waters.

But, in Smith’s hands, Eliza’s position is not secure. She is schooled in her upper-class, white privilege, first by Sarah, who drags Eliza through the realities of London poverty and then by Andrew Bogle.

His tale of life in Jamaica becomes a story within the story. Keeping accounts for Edward Tichborne (Roger’s uncle) in Jamaica and England, Andrew sees both sides: the money squeezed from slave labour to fund English profligacy, and its impact on slaves, such as his lover Young Johanna. He becomes a favourite of the mob during the trial because of his calm self-possession, but British discourses of human rights are little more than a strange spectacle when compared to his lived experience. Eliza is transformed by Andrew’s tale, but he remains unaffected by the queer lady journalist.

Readers drawn to Smith will find the novel’s representation of the complexities of race and colonisation compelling. For me, as much as Smith mocks the pedantry of Victorian novelists like Ainsworth, she herself falls in no small way into the pleasures of Victorian literature in this meticulously researched story, replete with detail.

Sharon Bickle does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.