When my husband and I booked the ski trip, winter was still months away, and we weren’t thinking about the snow. Fall was still crisp like a fresh notebook. What would turn out to be the hottest year ever recorded registered as pleasant in Vancouver, as long as you didn’t think too hard about how uncanny it was. It had been warm enough for the beach on Mother’s Day; summer had been a streak of blue-sky afternoons and autumn a bouquet of sunset foliage bright on the branch and blazing in the unseasonable sunshine. The strangling stench of wildfire smoke never quite reached us even as Canada’s worst ever wildfire season raged across the country. But by winter, it was impossible to ignore how eerie the warm, dry conditions had become. The arrival of the season felt like the beginning of a horror movie, when the initial pleasantries are suffused with sinister foreboding. Our winter coats stayed in the closet. We flew to Saskatoon to visit family, where December temperatures averaged 9 degrees above normal, another record broken. By the time we got home, just before Christmas, bewildered spring flowers were already peeking out of the ground.

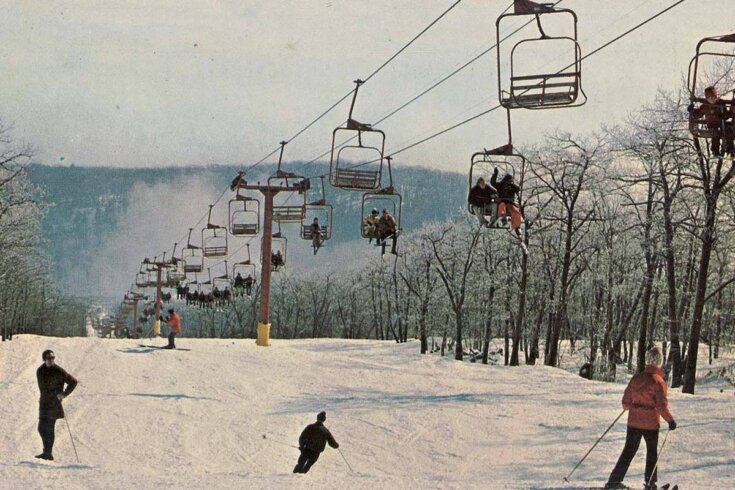

It was around then that I started second-guessing our ski trip, a concrete worry to distract me from the existential ones. My husband and I had modest ambitions: four days in mid-January at a ski resort where our daughter could learn to ski. My husband grew up on skis—as a baby, he would be tucked into a backpack by his father before they coasted together down the slopes of Fernie. I was more ambivalent. In my profoundly unathletic family, by contrast, the only competitive sport was speed reading, and I honed my creativity by coming up with new excuses to get out of running laps in gym class each week. Still, by the time I had graduated from high school, I had acquired the basics of both downhill and cross-country skiing from school trips and spent a few humiliating weekends learning to snowboard on the local hills under the tutelage of sadistic friends. I took it for granted that my kids would have the same opportunity.

With each year that passes, winter gets a little more conditional. As of January 1, British Columbia, which holds some of the most famous alpine playgrounds in the world, had only 40 percent as much snow as usual—the result of our unusually warm, dry autumn—and several specific regions in the province had their lowest ever snowpack levels. On the world-renowned peaks of Whistler Blackcomb, where fewer than half the runs were open at the end of December, disappointed skiers posted TikToks of slushy runs that fizzled into muddy plateaus. Across BC, December temperatures were breaking records as well. Speaking to The Narwhal, climate scientist John Pomeroy described the winter as “the desiccation of western Canada” and pointed to the province’s melting glaciers, which are expected to disappear entirely by the end of this century. Across Canada, snow cover has shrunk by 5 to 10 percent each decade since 1981. On West Vancouver’s Cypress Mountain, where I learned to snowboard twenty years ago, the average winter temperature has increased by 1.5 degrees since 1901, and annual snowfall has decreased by almost a third.

As winter becomes endangered, skiing seems like an endangered pastime, one with an increasingly high environmental cost. To compensate for the lack of snow, many ski resorts now rely on snow-making machines, which consume a tremendous amount of power and water. On average, Canadian resorts produce over 42 million cubic metres of snow, enough to fill 7,500 Goodyear blimps, and emit 130,095 tons of C02 in the process, the equivalent of adding more than 28,000 cars to the roads each year. Researchers from Canadian, European, and Australian universities expect that by 2050, climate change will increase the national demand for artificial snow by up to 97 percent—a country of Potemkin ski slopes concealing the grim reality of our disappearing winter.

The climate crisis is indisputably terrifying, but it’s hard to sustain a state of terror indefinitely. Even during a horror movie, you shovel popcorn into your mouth between the most gruesome scenes. According to the Media and Climate Change Observatory, global coverage of climate change decreased by 14 percent between 2021 and 2023. Catastrophes like the 2021 heat dome—the deadliest weather event in Canadian history—command our attention and trigger our panic. But what do we do the rest of the time as the accumulating losses of the climate crisis creep up around our ankles like the rising sea? Is it cruel to encourage my children to fall in love with a disappearing season, to pass along a hobby that may well go extinct in their lifetime? Or is it a kind of optimism, a gesture toward a still-possible future?

In early January, an Arctic front descended on the west coast; ski runs that had been closed from the lack of snow were now closed due to frigid temperatures. But by the time of our trip, conditions were deceptively normal: picturesque icing-sugar peaks, pillowy snowdrifts, and pleasant temperatures that hovered just below freezing. We arrived at the same resort where I had learned to ski in high school; in our cabin, the narrow bunk beds with their faded green coverlets and the chipped blue laminate of the kitchen table unleashed a flood of repressed teenage memories. I sent my best friend a video tour. “Oh wow—hasn’t changed one bit,” she replied immediately. Outside, everything was white, and gauzy clouds tangled in the hills, jagged with evergreens. My daughter scooped up snowballs and cradled them tenderly before hurling them into the air. We bundled up our baby in a red snowsuit and took photos of him nestled into a snowbank. It’s tempting to believe that things are fine, to put the dread aside until you’re standing directly in the path of the next crisis.

My daughter arrived for her first lesson certain that she knew how to ski, based on a Peppa Pig episode she saw once. She is at a tender age where she is beginning to grasp the distance between her ambitions and her abilities; she crumples up her drawings when they fail to match her vision, and I see in that gesture of abject frustration the heartbreaking and irrefutable evidence that she is growing up. Sooner than I ever could have imagined before I had children, they begin to grasp the truth of the world: things don’t always go the way you expect them to, no matter how badly you try. It turned out skiing was not as easy as Peppa had led her to believe, but my husband was patient, guiding her gently down the bunny slope. At four, she could not imagine herself in a future where she might overcome the frustrations of the present, but it was his job as a parent to help her see that it was possible, to encourage her not to give up.

The activist and author Rebecca Solnit calls climate despair a luxury, because it justifies passivity. “What motivates us to act is a sense of possibility within uncertainty—that the outcome is not yet fully determined and our actions may matter in shaping it,” she writes. “This is all that hope is, and we are all teeming with it, all the time, in small ways.” I don’t know whether my kids will become skiers—climate crisis aside, they might inherit my aversion to sports—but I know it’s worthwhile to teach them persistence and optimism, to show them that things can be changed.

The future is coming, and so much of it is bleak and uncertain—year by year, a little less forgiving of humanity’s continued failures. It’s easy to drown in despair for the past, what we imagine we’ve lost even as the present is right there in front of us, reminding us what we can still save. As for our kids, they don’t know any world but this one. This is the only time they have on earth; it’s the only time we have as well. The only thing we can do, our most urgent responsibility, is to teach them how to live in it.