Poetry isn’t a medium typically associated with towering beasts. Lyric poems tend to be short, tender and concerned with minor everyday incidents. That, or abstract concepts like love and death. Poems also tend to be thought of, wrongly or not, as true accounts – the inverse of creature feature films with preposterous special effects.

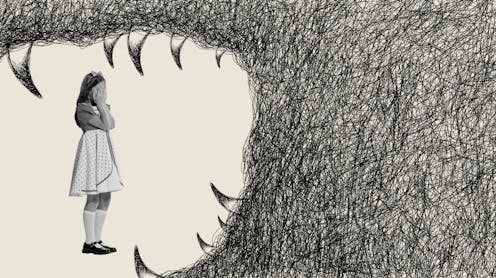

But poets, like everyone else, live in a world of disastrous events bigger than themselves. And the monster – particularly the giant monster – is an archetype that goes right back to ancient myth.

Talos, the bronze guardian of Crete, and Humbaba, the ogre of the Epic of Gilgamesh, are just two dangerous titans of literary history. It’s tempting to think that today we know enough about our surroundings to no longer be awed by the possibility of giants. But the truth is that there is still much that makes us feel small and vulnerable. Writing about huge monsters is one way of confronting that.

Two different anthologies of monster poetry are published this month in the UK. Ten Poets Defend Their Cities from Giant, Strange Beasts is edited by myself and Kirsten Irving and published by Sidekick Books. In it, poets envisage the outcomes of giant monster attacks on London, Cambridge, Glasgow and Liverpool, among other cities. These confrontations are frequently surreal, or representations of other kinds of epic battle.

Alex Adams and Aaron Kent’s Devastation Songs, meanwhile, is a compilation of writing about kaiju, the Japanese term for gargantuan fantasy creatures. In the foreword, Adams writes about how the monster movie is often used as a vehicle for “powerfully resonant social and political ideas”, pointing to recent Oscar winner Godzilla Minus One (2024) as an example.

Here are six more poems that deal in different ways with giant monsters:

1. Beowulf

Beowulf is an Anglo-Saxon epic poem about the defeat of Grendel – a creature whose exact form is still debated. Depending on which translation you read, Grendel is either a “grim demon”, a berserker, a “miscreated thing in man’s form”, or a “horrible stranger”.

Two things are certain, though: he is very large, and he is a violent murderer who must be destroyed.

Read more: Publishing Tolkien's Beowulf translation does him a disservice

2. La Géante (The Giantess) by Charles Baudelaire

This poem is from Baudelaire’s collection Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil, 1840-1867), which was dubbed “an insult to public decency” on publication.

The Giantess reflects some of the book’s controversial themes, revelling in erotic fascination. Far from opposing the giantess, the poem’s narrator wants to see her “grow without restraint”, imagining an expedition across her vast body. Here, Baudelaire proposes monstrosity as a realm of wonder and temptation.

3. Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll

One of Carroll’s (1832-1989) most famous poems, Jabberwocky is teeming with nonsense words (manxome, whiffling, burbled). This strange language keeps the titular Jabberwock obscured even as its fiery approach and defeat is recounted.

It makes for a faithful representation of monstrosity as a quality: we can perceive it, dream up words for it, even kill it, but we can never fully understand it.

4. The Man-Moth by Elizabeth Bishop

The epigraph to The Man-Moth explains that it was inspired by a misspelling of the word “mammoth”. Bishop’s man-moth isn’t necessarily a giant, but several lines allude to his having a giant’s perspective (“The whole shadow of Man is only as big as his hat”, “He thinks the moon is a small hole at the top of the sky”).

He is a sad, lonely creature who sheds a tear at the end of the poem. Bishop often wrote about the darkness in the human psyche, and her take on the subway-dwelling city beast is an allegory for urban alienation.

5. The Loch Ness Monster’s Song by Edwin Morgan

Scottish poet Edwin Morgan (1920-2010) specialised in linguistic play. The Loch Ness Monster’s Song is almost unintelligible – a brief burst of transcribed watery noises. But it could easily be a poem written in another language.

It challenges us to recognise that what we call “monstrous” might just be unfamiliar – not a threat, but an opportunity for connection.

6. Dragons by Matthew Francis

Every line of this poem, from Francis’ 2001 collection of the same title, ends in the word “dragons”. But the narrative is one of failing to find a single dragon.

This contrast is used to illustrate how monsters and creatures of myth loom large in our minds primarily as the result of our imaginations. In other words, we invent them to fill the gaps in reality. We need them, because without them there are too many clues pointing nowhere.

The poem isn’t available to read online, but you can read my own pastiche of it (framed as a “DVD extra”).

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Jon Stone is an editor at Sidekick Books.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.