While the opinion polls have been predicting it for many months, the achievement appeared to be no less seismic when the results finally began to trickle through.

Sinn Fein has swept aside many years of history and is on course to become the first nationalist or republican party to take the largest share of seats in a Northern Ireland Assembly election.

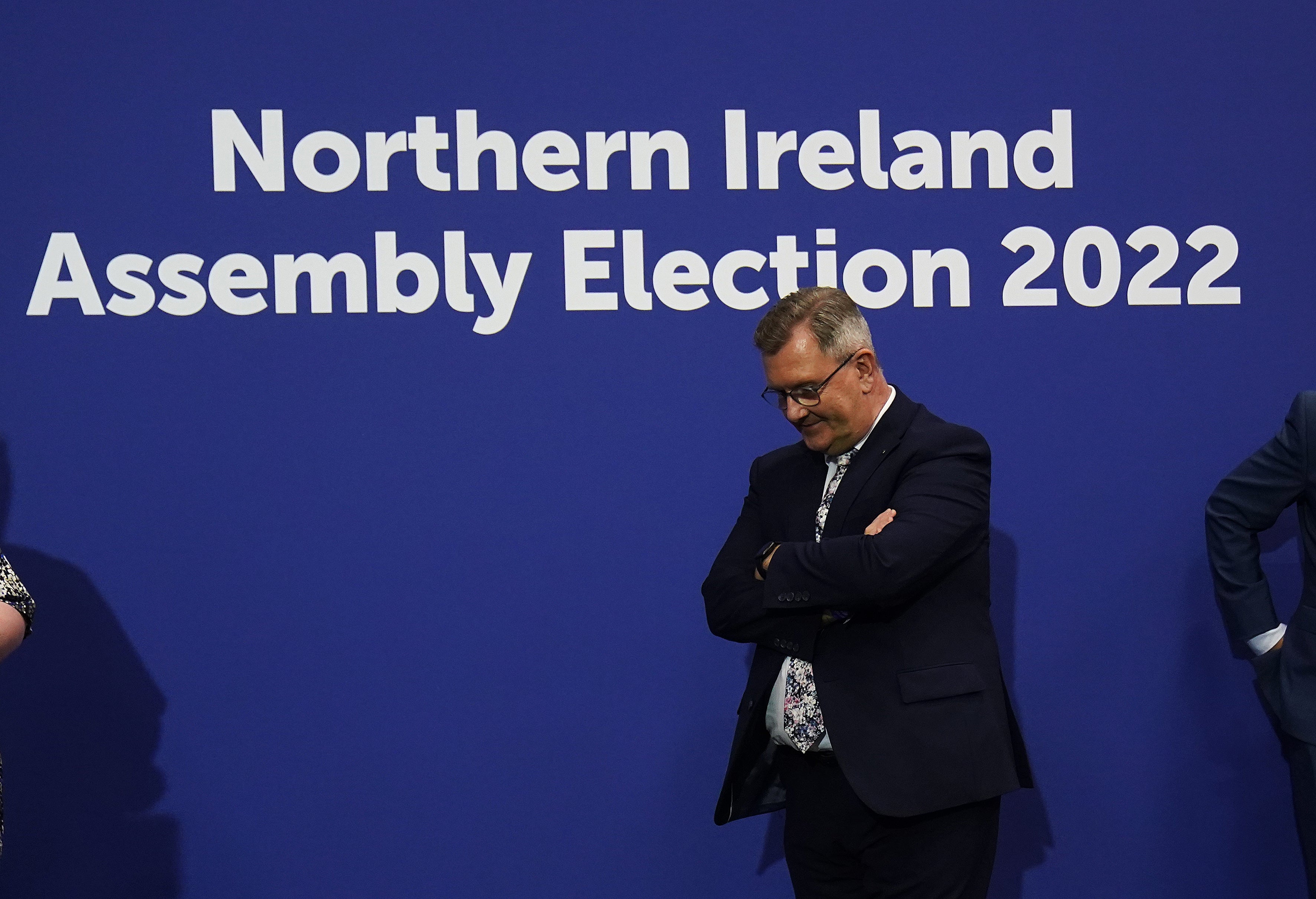

The results will be a significant psychological blow to Sir Jeffrey Donaldson’s DUP, which has lost its position as the biggest party for the first time since 2003, when it usurped David Trimble’s Ulster Unionists.

Safe in the knowledge that the election was in its hands, Sinn Fein ran a safety-first campaign, seemingly unwilling to engage in any electoral trench warfare, preferring instead to portray vice president Michelle O’Neill as the “first minister for all” in waiting.

The party also made a tactical decision not to labour the point over its desire to see Irish unity, concentrating instead on bread and butter issues such as the cost-of-living crisis and spiralling hospital waiting lists, which seem to have chimed positively with voters.

The DUP’s gamble on focusing its campaigning energy on unionist opposition to the Northern Ireland Protocol and raising the spectre of a Sinn Fein victory increasing the possibility of a border poll on unity was less successful, with the party dropping both in its share of first preference votes and overall seats.

The much anticipated Alliance Party surge has also become a reality in this election, with the cross-community party now set to become the third largest at Stormont.

The growing support for Naomi Long’s party shows an increasing percentage of the population in Northern Ireland who seem to want to move away from traditional orange and green politics.

The election has been a crushing disappointment for the smaller unionist and nationalist parties, the UUP and SDLP. Despite their leaders receiving positive personal ratings, any upsurge in support at the ballot boxes failed to materialise.

UUP leader Doug Beattie, who was spared the indignity of losing his Upper Bann seat, chose to contrast his approach to that of the DUP, insisting that he stood for positive politics, while Colum Eastwood of the SDLP won plaudits in the televised election debates of his articulate portrayals of the concerns facing voters.

However, both parties leave the election facing the headache that they are further away than ever from challenging the hegemony of the larger unionist and nationalist parties.

While the election is now settled, what is less clear is what it will all mean.

As the largest party, Sinn Fein is entitled by Stormont rules to nominate Ms O’Neill for the position of first minister.

However, Northern Ireland has been without a powersharing Executive for several months after the DUP withdrew in protest at the protocol, a post-Brexit trading arrangement hated by unionists because it creates an economic barrier between the region and the rest of the UK.

Sir Jeffrey has stated clearly that he will not re-enter government until his concerns are met, something which seems potentially even more distant after Secretary of State Brandon Lewis intimated on the eve of the election that there would be no new law overriding the protocol in the Queen’s Speech next week.

Even if unionist concerns over the operation of the protocol could somehow be resolved, Sir Jeffrey has so far refused to confirm that he would be prepared to take the position of deputy first minister in any Executive in which Ms O’Neill was first minister.

The DUP’s current position means that any imminent return of the Stormont Executive appears to be unlikely.

The new electoral landscape is now clear, but the political future for Northern Ireland remains as uncertain as ever.