The 1989 Tour de France is widely rated as the best ever modern-day edition of the race, featuring the narrowest of victories for Greg LeMond on the Champs Elysées ahead of Laurent Fignon in the final time trial.

LeMond's victory, his second in the Tour, also represented an incredible turnaround for the American after his near-fatal hunting accident in 1987 and two rollercoaster seasons that followed.

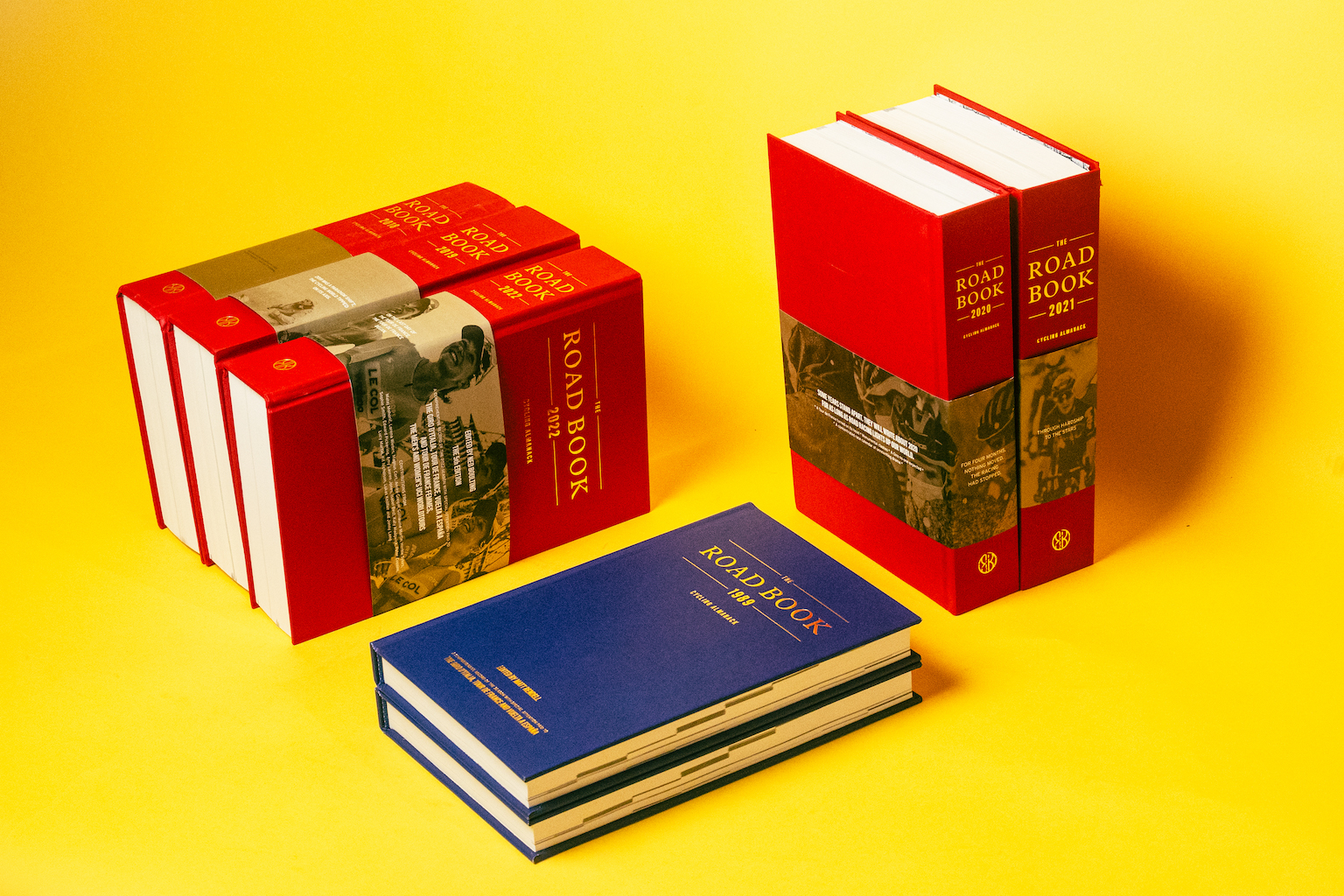

In this moving memoir of her and Greg's experiences, from The Road Book Blue Series, and history both on and off the bike in that period, Kathy LeMond provides an acute and warmhearted insight into how LeMond first found his way to Europe and conquered the biggest bike race in the world in a tumultuous year and when it looked like it was far from possible to achieve.

How it all began

The first time I ever saw Greg, he was sitting with his parents in a coffee shop. I was visiting a friend who was also a cyclist, and I saw him and his family happily talking together. I think it was because he had such a great relationship with his mom and dad that he wanted me to travel with him to races. There was something about how close they were. They could talk about anything and they always respected his opinion. It wasn't like they were just parents telling him what to do; that never was the case. They were just supportive, extraordinary people. His mom is gone now, but his dad is still alive.

You see, when we got married he was 19 and I was just 20. We were so crazily in love. We really didn't have anybody else. I don't even know how to describe it. It was just, you know, how it is when you first fall in love. We had been together a year and a half when we got married, and I just couldn't even imagine living without him.

Cyrille Guimard got him a ride when Renault offered him a contract. He, Bernard Hinault and Jean-Marie LeBlanc came to visit Greg at his parents' house in Reno. I mean, at 19, Greg was very young to turn pro. They were concerned about how it would work out because Americans often struggled in France; they could be lonely, unable to speak the language, although we both spoke a high-school level standard of French. And Greg was already making $35,000 a year in America, but only $12,000 in Europe.

Cyrille arranged a place for us to live only 15 miles from his house. It was meant in a supportive way, and not in any way negative. He made sure that I could also come to France with Greg because he felt he had signed a real diamond. He put his arms around us and said, 'OK, I'lI make this as easy as I can for you.' Greg took Berlitz classes and got a French tutor, whereas Cyrille tried to learn English so that he and Greg could communicate better.

Greg had the ability. I think he always thought he had the ability. He was sustained by the dream of winning the Tour de France. That kept him going through some very difficult periods.

I should fast-forward.

The fightback begins

1987 was the hunting accident. Then, in 1988, he'd crashed in one of the Classics, gouging his chin and damaging his tendon. Every time he tried to ride again, it would seize up and he wouldn't even be able to pedal. Every day for a week he tried, until he couldn't even walk any more. We should have probably got a surgeon to do it right away, but it took until July for him to be operated on. So the beginning of 1989 felt like he was almost starting over.

Everyone had a lot of sympathy for him, and there was a lot of goodwill, but it must have been very hard for him.

He finished sixth at Tirreno-Adriatico, and fourth at the Critérium International, but then he picked up the Epstein -Barr virus, which was the next blow. He went to California, where he was going to try and train. My dad was an immunologist and had been working with a viral vaccine that he gave to Greg - basically a diluted flu shot designed to have his immune system respond. And just before his next race, the Tour de Trump, Greg started to feel better. But it was still one thing after another and he was totally out of shape.

At this time, I was about four months pregnant with our daughter Simone. I was seeing an obstetrician in the States because the plan was to have the baby back in America in October, after the end of Greg's season. I had given a routine blood test, and the next week Greg had to fly to Italy for the Giro. I took him to the airport in the morning, and I was due to fly with our two sons to Belgium in the afternoon. But when I got back home from seeing Greg off, the phone rang. It was the doctor.

I'm afraid you've got some bad results here. I'm so glad you haven't left.'

I told him that my plane was at two o'clock.

'I'm sorry, but you can't go. We need to talk.'

It seemed there were indications of possible Down's syndrome and further complications.

They wanted me to undergo an amniocentesis test. At the same time, my cousin Geoff (who we named our son Geoff after) was working as a stuntman in a Chuck Norris film in the Philippines and he ended up being killed in a helicopter crash. It was just a family nightmare.

In the meantime, Greg was starting the Giro having just found out that there was something potentially wrong with his daughter. On stage 2 to Mount Etna he lost eight minutes, and that night he called home and told me he was thinking he should just quit the sport altogether.

If you think you're going to lose a child, a cycling career suddenly doesn't seem very important. It gave him some perspective, just as it had done after his hunting accident: the most important thing was that he survived - that was a freaking miracle in itself; everything else was gravy. Now we still had another 14 days to wait for news on our daughter.

I wish people understood what it's like to be a professional athlete. When you see a cyclist not doing well, you have no idea what is actually going on in their lives. Their profession takes up 85 per cent of the energy they have for a day of living. They only have 15 per cent spare energy left for anything else. How best to use it? Greg was a father, a husband, a son.

When Greg joined Renault, the first thing they did was tell me what they expected from me: 'You do the laundry and cook for him. He needs three great meals a day.' But I made my views known too. I was just really lucky that Cyrille Guimard was open to my coming to the races because he thought it would be better for Greg. If I'd gone to the races and become an energy drain, they'd have kicked me out in a split second. Or if another rider had complained about me, I wouldn't have been able to stick around. There's no way they'd have put up with a wife who made a drama and wasn't fully supportive.

For those two weeks while I waited for the test results, I was having labour pains from the amniocentesis, and I couldn't get off the couch. I was worried I was going to lose the baby.

Then, one afternoon, I got a call that everything was fine. I'm not kidding, I got on a plane that afternoon with the two boys and we flew straight to Italy to be with Greg. Suddenly everything was OK! If you've had kids, you'll know how precious they are to you and that you'd die for them. We followed the race in the team bus for four or five days and it was just great: Greg could just ride again, rather than worrying about everything else.

On the last day of the Giro, it all came together, and Greg finished second in the time trial. He beat Fignon, putting over a minute into him. That gave him so much confidence going into the final 1989 Tour de France time trial. He was thinking: I've already beaten him by this much, and I wasn't feeling as good then as I'm feeling now. So he figured he could beat him. I mean, he always used to beat Fignon in time trials. The only question was: Can I beat him by enough?

1989

I was there in Luxembourg at the beginning of the Tour. Greg couldn't believe what happened to Delgado [missing his prologue start time and effectively losing the Tour - Ed.]. I just remember him saying, ‘That's insane. How could his team have allowed that to happen?'

Greg's parents followed the entire Tour. I was on the race with the kids until it came close to our house in Kortrijk, and then we went home for a while. The riders flew from Belgium to Dinard. On the plane, Greg sat next to race director Jean-Marie Leblanc.

Remember that Leblanc had visited Greg with Hinault and Guimard in Nevada when they were signing him. Back then, he'd been the main cycling journalist for L'Equipe, and it had been a big story for him. After that, when Greg had been shot in 1987, I was eight months pregnant with our second boy. I had gone into labour while Greg was being operated on for his shotgun wounds. It had been a nightmare. I got to see Greg in the recovery room, and I kissed him before I got sent to another hospital for the birth. A day or so later, they let me leave my hospital to go and see Greg for a few minutes because he'd regained consciousness.

Just as I was going into the hospital, at around midnight, there was Jean-Marie Leblanc, sitting outside.

'Kathy!" he'd said. 'What's going on? They won't let us in the hospital. Can you tell us anything?'

I told him that I didn't know anything and that I hadn't even seen Greg.

'I'm here for as long as it takes,' he told me. I have to see Greg before I go back to France.

Please can you get me to him?'

Now, there were a lot of journalists there. It was a big national news story at the time. But Jean-Marie never left. Every time I came or went from the hospital over the next days, Jean-Marie was always there. On the fourth day, I said, 'OK, I'll see what I can do.' And he was the only person outside of family who saw him. When he saw Greg, he couldn't stop crying.

Greg was in terrible, terrible shape. So Jean-Marie really knew what Greg had been through.

And sitting next to him on that plane at the Tour, two years later, he asked Greg if there was anything he could do for him.

'You know what? said Greg. I need a car pass for my wife. I need her to be able to come and see me. If I go on to win this race, I will not get on the podium unless my wife is there.'

Immediately, I had a car pass and accreditation organised. It was the first time any rider's wife had been given them. The next day, after the time trial on stage 5, Greg took the yellow jersey. We were absolutely euphoric. It had been so long coming. He probably called me five times, and that was before cell phones! The hotel operator had to put the call through, or he had to go down to the lobby. We must have talked on the phone until four o'clock in the morning.

On the rest day before the Alps, I drove down, and then I followed the rest of the race the whole way to Paris. I was following the race, but in many ways I was no different to any other spectator. I could only go as far as the hotel lobby. I was never at the dinner table. I always stayed at another hotel. No one on the team took the slightest responsibility for anything to do with me. If I was there, I always made sure I was standing off to the side. I was really just there so that Greg had someone he could talk to at the end of a stage, someone he could trust 100 per cent. He needed to be able to play with the kids, switch off, talk about other things - fly-fishing, for example. Or he'd read a book about something else. Greg used to travel with textbooks he'd bought from the University of Brussels. He travelled with my organic chemistry books from college so that he could find out about the Krebs cycle. He only wanted facts. Cycling was a land of superstition and weird practices. He just wasn't interested in that.

Greg didn't know if he could race in the high mountains to come. He didn't know if he would crack. He rode super-defensively because he wasn't 100 per cent himself. Since being shot he'd never ridden a great race, so he was terrified. I mean, he literally had shotgun pellets in his heart. We didn't know what he might or might not be capable of. We didn't know what we didn't know.

He had a bad day on Alpe d'Huez. And the next day, I thought it was the end of the Tour for Greg after the stage to Villard de Lans. He thought so too. I remember Greg's mum and dad were with us that night, just sitting around, having a Coke and just talking. His parents were amazing: no expectations, no pressure; just let him vent, he'll figure it out. He won to Aix-les-Bains the next day.

Greg had been OK with Fignon taking the yellow jersey from him. Leading the race had been a lot of extra pressure. And Fignon had been saying that Greg wasn't riding aggressively enough, which made him absolutely furious because he'd seen Fignon hanging on to a motorbike. Greg said, 'Don't even go there. You should be out of this race.'

One day I was staying in the same hotel as Fignon's wife. She was working as a journalist on the race and asked me if she could join me for breakfast. We were having a nice, polite conversation when she suddenly said to me, 'Is Greg being just the biggest asshole right now?"

"No,' I said.

"Oh my God,' she said. 'I cannot stand Laurent right now.'Then she told me she didn't want to see him any more.

Greg couldn't believe it when I told him what she'd said. 'You gotta be kidding me! She told you that?'

The thing is, when Fignon wasn't winning, he was fine. We had so many mutual friends, so I knew he wasn't all bad. And after they both retired, Greg and Laurent had some really great conversations. But when Fignon was on top, he was just the worst.

The whole family was on the Champs-Elysées. Our babysitter in Belgium brought the two boys down to Paris. I drove there the day before, pregnant with Simone, and met with my parents, who'd come for the whole of the final week of the Tour. Greg's parents were there too. We had a hotel right by the Eiffel Tower.

On the morning of the final time trial, I left Greg alone. On time trial days, I let him reach out to me; I never reached out to him because he was focused in a different way to on other days

My dad said, 'I think he's going to win it.'

'C'mon, Dad,' I said. 'Let's just be happy with second. I don't think he'll win. I think it's too much. I don't want that pressure on him, and I don't want to be disappointed.'

From where we had been not that long before, second place in the Tour de France would have been a miracle. But I guess that's why I never won anything big! When the race started, within the first kilometre, I thought: Oh my God, he's good today. Maybe. Maybe. But it is going to be close. What I didn't know at the time was that my dad later took a cab to Greg's hotel with our five-year-old, Geoff. He'd just wanted to go there and tell Greg that he thought he could win. But they never made it back to join us in the VIP area and so they had to watch the race like any other spectators, from behind the fence when Greg came in. But when Greg got onto the podium, he spotted my dad and Geoff, who he hadn't seen for three weeks.

That's how Geoff ended up in all the photos with Greg on the podium.

The new 1989 Blue Book edition, from the publishers of The Road Book, captures one of the most remarkable years in professional cycling history. Order your first edition copy from a strictly limited print run for £40 from www.theroadbook.co.uk