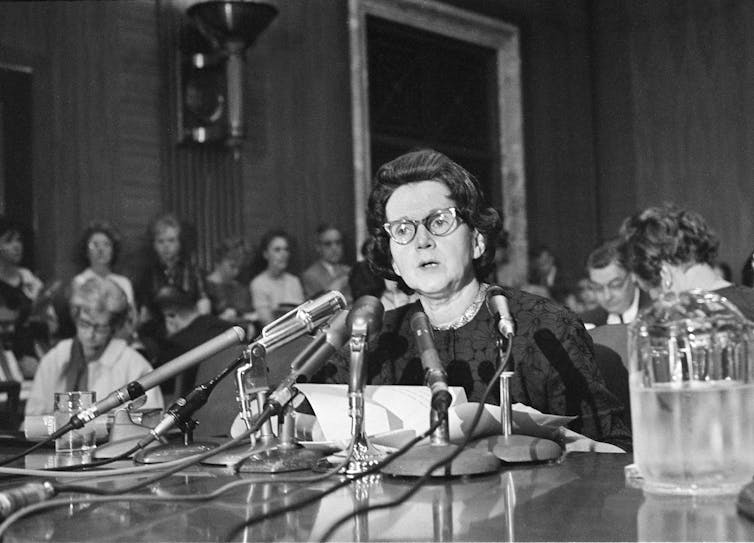

In 1962 environmental scientist Rachel Carson published “Silent Spring,” a bestselling book that asserted that overuse of pesticides was harming the environment and threatening human health. Carson did not call for banning DDT, the most widely used pesticide at that time, but she argued for using it and similar products much more selectively and paying attention to their effects on nontargeted species.

“Silent Spring” is widely viewed as an inspiration for the modern environmental movement. These articles from The Conversation’s archive spotlight ongoing questions about pesticides and their effects.

1. Against absolutes

Although the chemical industry attacked “Silent Spring” as anti-science and anti-progress, Carson believed that chemicals had their place in agriculture. She “favored a restrained use of pesticides, but not a complete elimination, and did not oppose judicious use of manufactured fertilizers,” writes Harvard University sustainability scholar Robert Paarlberg.

This approach put Carson at odds with the fledgling organic movement, which totally rejected synthetic pesticides and fertilizers. Early organic advocates claimed Carson as a supporter nonetheless, but Carson kept them at arm’s length. “The organic farming movement was suspect in Carson’s eyes because most of its early leaders were not scientists,” Paarlberg observes.

This divergence has echoes today in debates about whether organic production or steady improvements in conventional farming have more potential to feed a growing world population.

Read more: Would Rachel Carson eat organic?

2. Concerned cropdusters

Well before “Silent Spring” was published, a crop-dusting industry developed on the Great Plains in the years after World War II to apply newly commercialized pesticides. “Chemical companies made broad promises about these ‘miracle’ products, with little discussion of risks. But pilots and scientists took a much more cautious approach,” recounts University of Nebraska-Kearney historian David Vail.

As Vail’s research shows, many crop-dusting pilots and university agricultural scientists were well aware of how little they knew about how these new tools actually worked. They attended conferences, debated practices for applying pesticides and organized flight schools that taught agricultural science along with spraying techniques. When “Silent Spring” was published, many of these practitioners pushed back, arguing that they had developed strategies for managing pesticide risks.

Today aerial spraying is still practiced on the Great Plains, but it’s also clear that insects and weeds rapidly evolve resistance to every new generation of pesticides, trapping farmers on what Vail calls “a chemical-pest treadmill.” Carson anticipated this effect in “Silent Spring,” and called for more research into alternative pest control methods – an approach that has become mainstream today.

3. The osprey’s crash and recovery

In “Silent Spring,” Carson described in detail how chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides persisted in the environment long after they were sprayed, rising through the food chain and building up in the bodies of predators. Populations of fish-eating raptors, such as bald eagles and ospreys, were ravaged by these chemicals, which thinned the shells of the birds’ eggs so that they broke in the nest before they could hatch.

“Up to 1950, ospreys were one of the most widespread and abundant hawks in North America,” writes Cornell University research associate Alan Poole. “By the mid-1960s, the number of ospreys breeding along the Atlantic coast between New York City and Boston had fallen by 90%.”

Bans on DDT and other highly persistent pesticides opened the door to recovery. But by the 1970s, many former osprey nesting sites had been developed. To compensate, concerned naturalists built nesting poles along shorelines. Ospreys also learned to colonize light posts, cell towers and other human-made structures.

Today, “Along the shores of the Chesapeake Bay, nearly 20,000 ospreys now arrive to nest each spring – the largest concentration of breeding pairs in the world. Two-thirds of them nest on buoys and channel markers maintained by the U.S. Coast Guard, who have become de facto osprey guardians,” writes Poole. “To have robust numbers of this species back again is a reward for all who value wild animals, and a reminder of how nature can rebound if we address the key threats.”

Read more: Ospreys' recovery from pollution and shooting is a global conservation success story

4. New concerns

Pesticide application techniques have become much more targeted in the 60 years since “Silent Spring” was published. One prominent example: crop seeds coated with neonicotinoids, the world’s most widely used class of insecticides. Coating the seeds makes it possible to introduce pesticides into the environment at the point where they are needed, without spraying a drop.

But a growing body of research indicates that even though coated seeds are highly targeted, much of their pesticide load washes off into nearby streams and lakes. “Studies show that neonicotinoids are poisoning and killing aquatic invertebrates that are vital food sources for fish, birds and other wildlife,” writes Penn State entomologist John Tooker.

In multiple studies, Tooker and colleagues have found that using coated seeds reduces populations of beneficial insects that prey on crop-destroying pests like slugs.

“As I see it, neonicotinoids can provide good value in controlling critical pest species, particularly in vegetable and fruit production, and managing invasive species like the spotted lanternfly. However, I believe the time has come to rein in their use as seed coatings in field crops like corn and soybeans, where they are providing little benefit and where the scale of their use is causing the most critical environmental problems,” Tooker writes.

Read more: Farmers are overusing insecticide-coated seeds, with mounting harmful effects on nature

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archive.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.