Hell is a teenage girl, or that's what Silent Hill: The Short Message would have you believe. Subtle as a brick to the nose, Konami's compact horror game-slash-walking simulator foregoes any metaphorical flair in favor of simply screaming its themes in your face repeatedly. It's as if the writers picked five or six of the most traumatic things they could possibly imagine happening to a young woman and condensed them into a single video game experience. I stifled more laughs than I did screams, though, because I've never seen such delicate matters handled with so clumsy a touch.

As a Silent Hill fan, I don't consider the whole thing a waste of my time, but the very concept of The Short Message feels wasted on itself. There are multiple missed opportunities for deeper, symbolic storytelling, from questions of physical displacement, hopelessness, and the distinct ways that Eastern versus Western cultures view death by suicide. But all this just makes Konami's approach to its subject matter even more bizarre. The Short Message opts for garish shock value and predictable trivialization of teenage girlhood in its attempt to stay current, bold, and daring, and through doing so, has blunted my emotional response to it entirely.

Warning: spoilers ahead for Silent Hill: The Short Message, as well as explorations of the game's sensitive themes, including suicide

Killing joke

Here's what GR+'s Leon Hurley thinks of Konami's shadow-dropped morsel of terror in our Silent Hill: The Short Message review.

I laugh out loud as Anita's closing monologue reveals that she was meant to be 18 years old this whole time. I'm not sure if anyone at developer HexaDrive has ever met a late-teenage girl, let alone spoken to one, but I wouldn't be surprised if not.

To be fair, The Short Message is not the first horror game to juggle these topics, drop the ball, and then boot it even further afield. Poor handling of women's stories and of mental health in general is so endemic in the horror genre that I'm desensitized to it by now (though I shouldn't have to be). Imagine my total lack of surprise to once again see the complexities of female adolescence being boiled down to their most stereotypical parts: we are bitches, we are melodramatic, we crave attention, and oh boy do we love killing ourselves to get back at each other.

I'm pretty sick of that narrative. It's 2024 and we have the internet. You'd expect writers to know by now that horror games can terrify without tropes, and that there's a lot more to depression and suicidal ideation in young people than the grotesque blame-gamery as seen in 13 Reasons Why. Alas, The Short Message risks regurgitating those damaging ideas seven years since that awful show first aired.

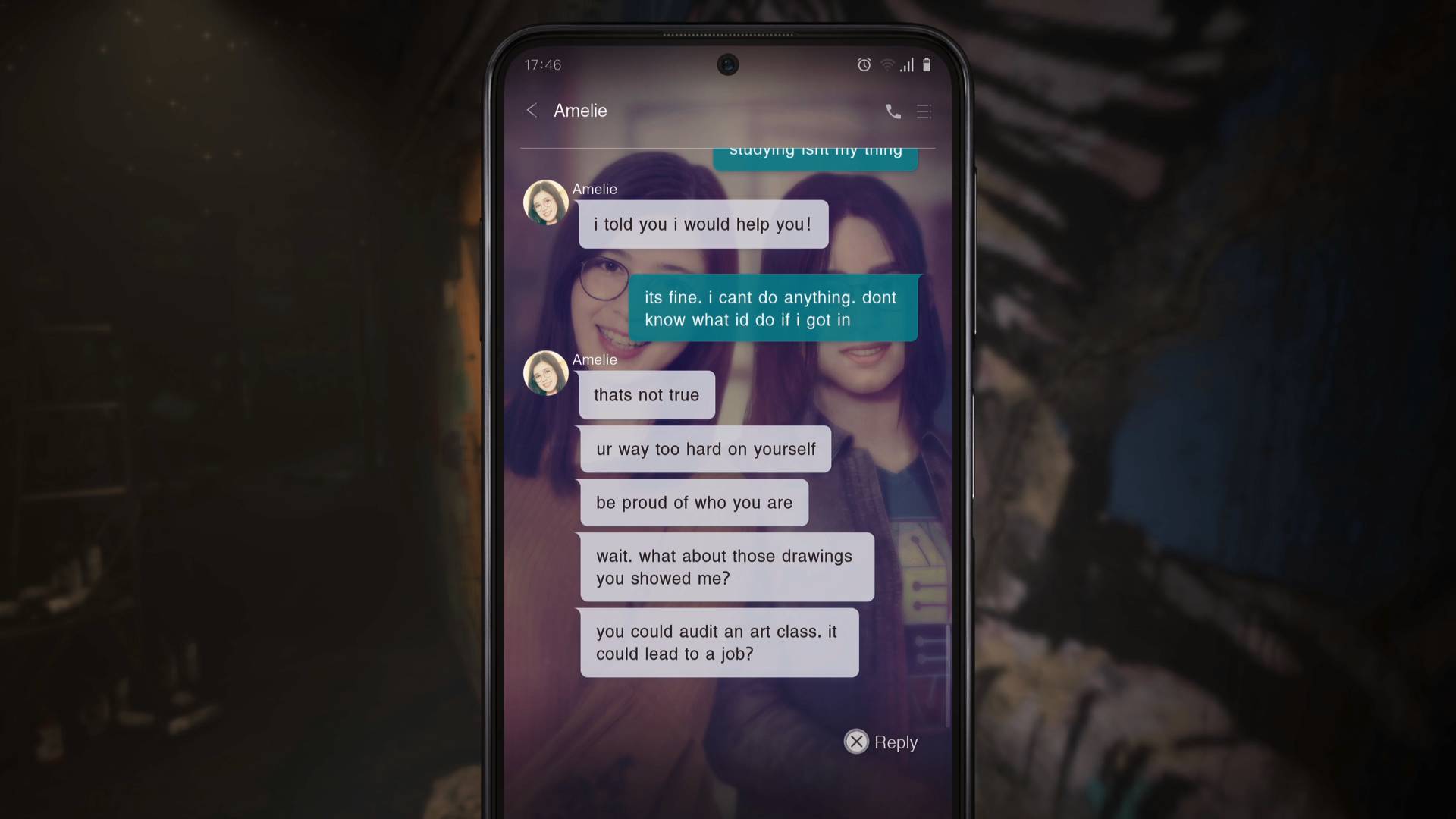

For all the suicide prevention screens and trigger warnings the game throws up between chapters, The Short Message is perfectly happy to exploit these themes to be provocative. Sitting through grim vignette after grim vignette feels like watching episodes of an extremely tragic soap opera, each one more over-the-top than the last as I'm quickly overloaded by the drama of it all. I lose it when Anita starts sobbing over her 200-odd followers demanding "more sexy pics" from her. She then throws herself off a rooftop because she is jealous that she does not have as many followers as her dead friend Maya. Wait, what?

The Short Message is commenting on the very real negative impact that social media can have on teenage mental health. By being so literal about it, however, the writers have totally missed the point. There's more to her emotional state than her follower count, of course, but The Short Message stops digging there. At the end of the day, the true horror is in how much has been left untapped and over-spoken. It wants to emulate the claustrophobic cat-and-mouse horror of P.T, but fails to do more than parody young women.

Wasted potential

The very concept of The Short Message feels wasted on itself.

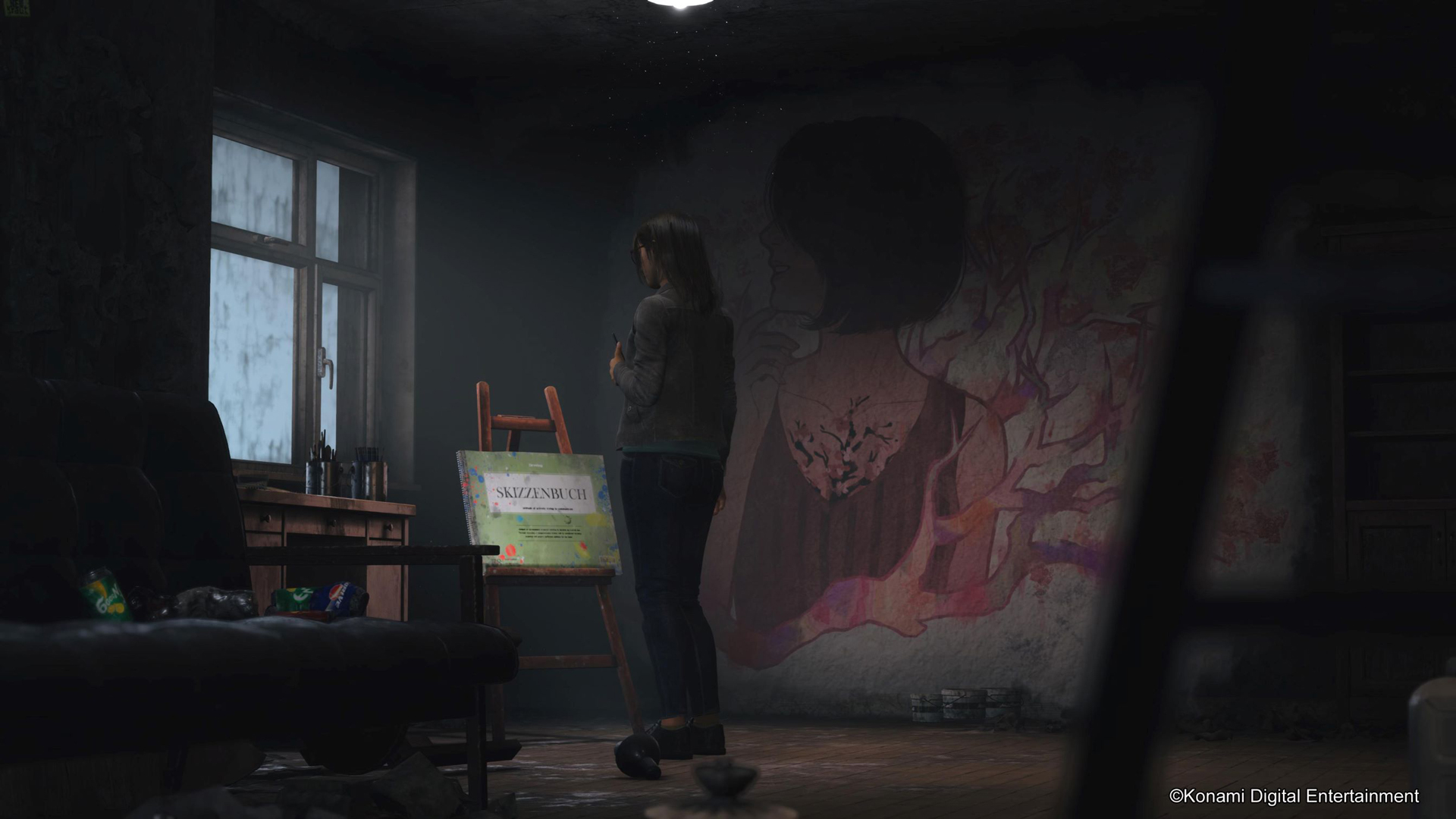

I'll be honest: I loathe this game, but there are many themes I do resonate with in Silent Hill: The Short Message. Interacting with various items as I explore the Villa, I learn about its setting in the economically downtrodden town of Kettenstadt. These moments are when I begin to see what makes this a Silent Hill game.

Coming from a Japanese publisher, Konami effectively evokes a sense of physical as well as emotional displacement in The Short Message. Kettenstadt is in Germany, two of our characters appear to be Japanese, and they all talk to each other in English. It definitely makes me stop to reconsider what I think is happening and where it might all be taking place, including whether or not it even matters. The Villa therefore becomes a liminal space that sits between worlds, between cultures – much like the three central characters we get to know there.

Beneath all the jarring J-drama of it all, the most fascinating element of The Short Message to me is the concept of a "beautiful death" and how it breaks cultural boundaries. It feels like HexaDrive is breaking the fourth wall to address their assumedly Western audience, explaining the cultural roots of Maya's romantic view of suicide and how ancient Japanese practices like hari-kiri have framed the nation's perception of it. Not that western literature is any less guilty of turning suicide into an aesthetic statement; ever since Shakespeare's lovesick Ophelia drowned herself in a fit of 'madness', stories lauding praise and respect upon dead women who were misunderstood in life can be found everywhere. Maya is the martyred Ophelia in this story, her value hinged on an unattainable legacy that she fears can only be achieved in death. The Short Message literally spells out its most fascinating and relevant idea– that in this cross-cultural context of life, death, and legacy, "the life they value is not biological but social" – and refuses to run with it for long enough.

As such, I've come away disappointed by Silent Hill: The Short Message. Earnest an attempt as it might be to bring one of the best-loved horror franchises firmly into 2024, it feels more regressive than ever. I don't understand what happened. Silent Hill 2 engages imaginatively with symbolic yet equally horrifying representations of trauma, and we've seen stronger female characters in the series before in the likes of Silent Hill 3. So why do Anita, Amelie, and Maya feel like such huge steps backwards? It's probably because these are throwaway characters. We're not meant to look much deeper than their backstabbing, bullying, convoluted behavior, because the writers didn't seize what else they had besides – and maybe they didn't even see it for themselves.

There's more to Silent Hill than Pyramid Head. Check out the best Silent Hill games from across the legendary series.