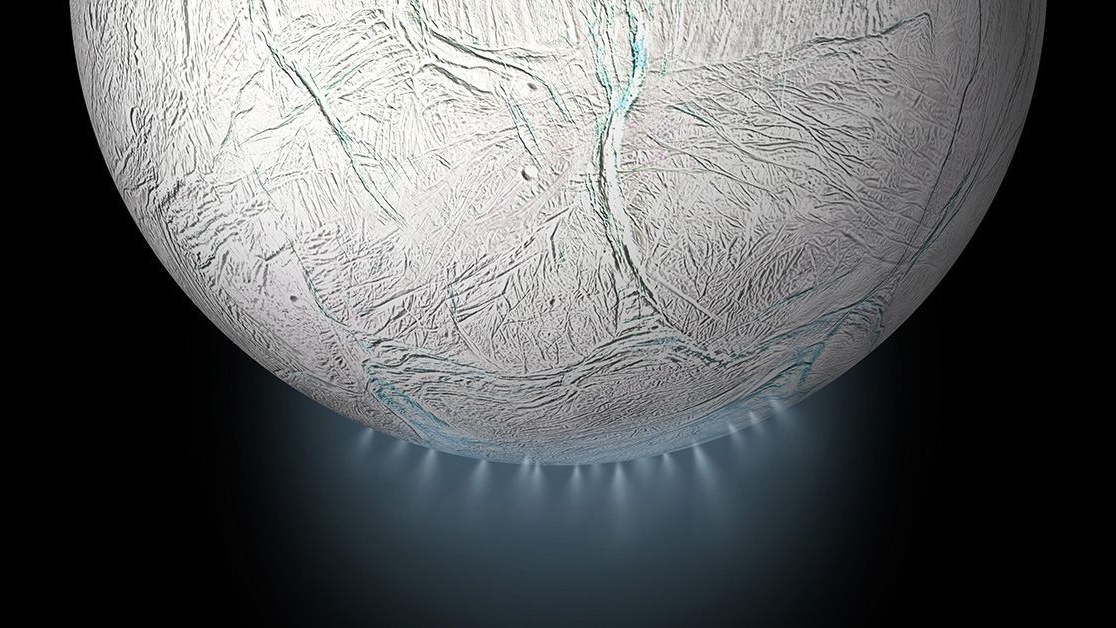

When NASA's Cassini spacecraft turned its instruments to Saturn's moon Enceladus, it observed plumes of ice shooting up from the moon's surface at speeds of about 900 miles per hour (1,448 kilometers per hour). These geysers seemed to be the tendrils of a vast subsurface ocean — and made scientists curious if their fluid might carry life signs, organic molecules.

But if scientists want to study those organic molecules, they'll need to find a careful way of collecting them without destroying them. There is now good news on that front: If one lab experiment is correct, then any possible amino acids in those geysers' fluid are expected to easily survive contact with a spacecraft.

Researchers learned this in the lab by working with a physical apparatus designed to examine collisions. The researchers created ice particles by pushing water through a high-voltage needle; the charge fragmented the water into tiny droplets, each of which crystallized into an ice grain as it entered a vacuum. Then, the researchers shot the hardened grains through a spectrometer and imaged each grain as well as recorded impact times.

They found that amino acids within the ice grains could survive impact speeds up to 9,400 mph (15,128 kilometers per hour). That's more than enough to survive an encounter with a space probe.

Related: Saturn's moon Enceladus has all the ingredients for life in its icy oceans. But is life there?

To determine if ice contains fingerprints of life, scientists want to get undamaged ice grains so they can get a clear read on compounds that lie within the ice. "Our work shows that this is possible with the ice plumes of Enceladus," Robert Continetti, a chemist at the University of California San Diego and one of the researchers behind the work, said in a statement.

And while the experiment used data from Enceladus, it has consequences beyond one moon of Saturn. If similar amino acids exist on other water-bearing moons, like Jupiter's Europa, then missions like the future Europa Clipper might be able to find them in ice grains as well.

The researchers published their work on Dec. 4 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.