The financial relation between the Union and various State governments has been a matter of vigorous debate. In a recent development, the Government of Kerala has approached the Supreme Court for a resolution of the following question: how much can the State government borrow from the market to bridge the excess of its expenditures over receipts? The Union government says that the borrowing should be limited to 3% of the State’s income or Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP). Kerala contends that by curtailing its borrowing powers, the Centre is undermining the State’s ability to fulfil some of its basic financial commitments and violating the principle of federalism.

How States spend more

It is well known that in India the power to raise taxes rests largely with the Union government while a greater part of the overall government spending is done by the State governments. More importantly, when it comes to spending on sectors which affect people’s daily lives, the overwhelming responsibility lies on the shoulders of the State governments. On social services, which include health and education, the expenditure incurred in 2022-23 was ₹2,230 billion (1 billion = ₹100 crore) by the Union government while the combined expenditure by all State governments was ₹19,182 billion. The expenditures of all the States put together was bigger than the expenditure of the Union by 8.6 times in social services as a whole; 2.6 times in education; and by 3.8 times in health.

Of course, the spending priorities of the Union and the States are guided by the constitutionally allocated powers and functions for them. Compared to its expenditure on social services, the Union government’s spending on defence was approximately twice as high, while its spending on transport, urban development and energy combined was 2.4 times higher.

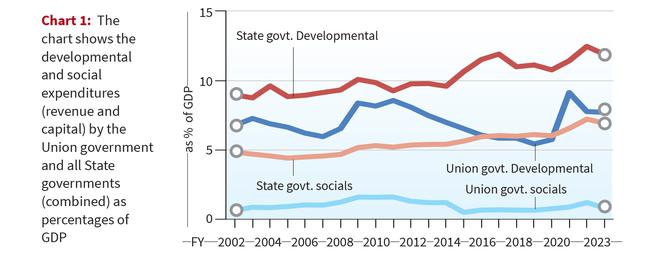

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has categorised the budgetary expenditures by the Union and the State governments as ‘developmental’ and ‘non-developmental’. The former includes expenditures on social services and economic services (such as on agriculture and industry) while the latter refers to interest payments, pensions, subsidies, and so on. It is remarkable that developmental expenditures, and within that, the expenditures on social services incurred by the State governments have risen significantly over the last two decades. As a proportion of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the combined developmental expenditures by all State governments increased from 8.8% in 2004-05 to 12.5% in 2021-22. On the other hand, the social and developmental expenditures by the Union government remained somewhat unchanged over the two-decade period. The upsurge in spending during the 2008-12 period was reversed over the next eight years, with a brief revival after 2020 (Chart 1).

In the end, it was the spending by the State governments that has helped to alleviate the livelihood crisis in the country, caused due to the slow growth of rural incomes and employment.

Kerala’s experience

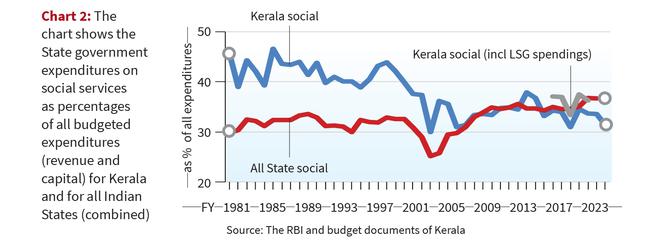

Kerala provides an excellent illustration of the power of government spending to positively transform a region’s economy and society. The expenditure on education, health and other social sectors as a proportion of the total budgeted expenditures by the State government in Kerala ranged between 40% and 50% for four decades, from the 1960s until the end of the 1990s. The proportion of social sector spending in Kerala was way ahead of the corresponding average of all other States until the middle of the 2000s. From the mid-2000s, while the average proportion of all other States rose upward, the proportion for Kerala stagnated. A substantial part of Kerala’s budget (6% in 2022-23) is now devolved to Local Self-Governments (LSGs). If the spending by the LSGs on social sectors is taken into account, the proportion for Kerala could still be higher than the average of all other Indian States (Chart 2).

A sizeable chunk of the government expenditure on social services is in the revenue account, paid as salaries and for covering day-to-day expenses. In fact, the large body of teachers, nurses, and other government employees in Kerala — half of them women — have been a key driver of the State’s social achievements over the decades.

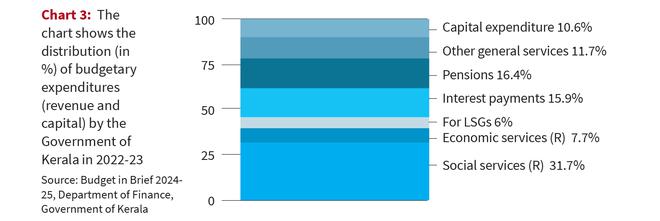

At the same time, the pensions paid to retired government employees as well as to members of the disadvantaged sections (such as the elderly, agricultural workers, widows) make up 16.4% of all budgeted expenditures by the Kerala government. This is markedly higher than the average proportion allotted for pensions by all Indian States (9.7%). It is indeed a concern that only 10.6% of Kerala’s budgetary resources was directed to capital expenditure (in 2022-23), which is much needed to build new infrastructure and institutions to speed up future growth (Chart 3).

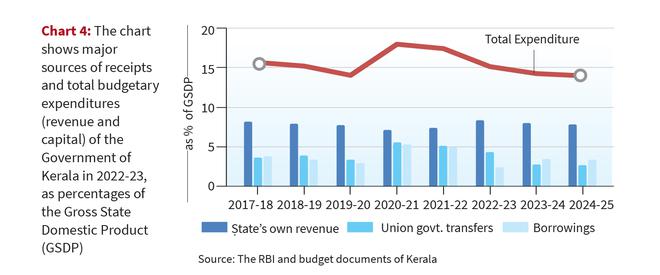

State governments receive funds from three sources: own revenues (tax and non-tax); transfers from the Union government as shares of taxes and as grants; and market borrowings. In 2020-21, the Kerala government had sharply increased its spending to 18% of its GSDP, to provide economic relief in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, aided by the relaxation in borrowing norms then. As ratios of GSDP, the Union government’s transfers to Kerala declined to 2.8% in 2023-24, significantly lower than previous years, even as the State’s own revenues remained at around 8.0%. This meant that, in 2023-24, the State government could meet its modest budget expenditure, equivalent to 14.2% of GSDP, only by raising the borrowing to 3.4% of the GSDP — which, however, would cross the borrowing limit set by the Centre (Chart 4).

The Supreme Court has now referred Kerala’s plea for additional borrowing to a Constitution Bench.

A case for more government spending

For Kerala to translate its enormous advantage in the social sphere to advances in domestic income creation, there need be more — not less — government spending.

Especially so on higher education and research that will help build a facilitative environment for a knowledge-driven economy. Given the current state of federal fiscal relations, such an increase in government spending can occur only with greater market borrowings.

A large part of the government borrowing in Kerala, as elsewhere in India, is from domestic financial institutions, including public sector banks and insurance companies, which mobilise savings from the wider public. Kerala is a region with a large reserve of private savings, which could be channelled for productive purposes.

The concerns about debt-financed government expenditures are often exaggerated. Economists in the Keynesian tradition have shown that government borrowing can generate a virtuous cycle if the borrowed resources are deployed effectively to create new incomes and jobs. Many of the development dilemmas that Kerala faces today — an ageing population, the large outgo for pensions, outmigration of its youth — are problems that most other States will also face in the coming years. The Union and the State governments should join hands to ward off these challenges. On its part, Kerala should be able to convince that its borrowing is part of a larger plan to rebuild the economy and not a firefighting exercise to meet immediate financing needs.

Jayan Jose Thomas is a Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi.