With polls showing Labour enjoying a significant lead over the Conservatives for well over a year, a key question as the election campaign picks up pace is whether Rishi Sunak can do anything over the next few weeks to turn things around. With one of his own ministers reportedly having gone on holiday rather than participate in the opening days of the campaign on the ground, it seems some of his own team may have already given up.

In truth, when the first national surveys of voting behaviour in Britain were conducted in the 1960s, there was a good deal of scepticism among political scientists about whether British election campaigns, which are relatively short, actually had any effect on the results.

The argument was that by the time the official campaign started, it was too late to make any significant difference to the outcome. With just 25 working days to appeal to voters, it was largely felt that a party’s win or loss was already baked in by the time the campaigns started.

However, the surveys helped to change this view. There is now a lot of evidence to suggest that much can change during the campaign itself as the parties unveil policy positions, meet the public, and knock on doors. One way of showing this is to monitor the extent to which voting intentions change during a campaign.

The 2017 general election provides an example of such change. A YouGov poll published on May 3 – the very beginning of the campaign – put the Conservatives on 47% in vote intentions, with Labour on 28% and the Liberal Democrats on 11%. When the votes were counted after the June 8 election, the Conservatives won 43%, Labour 40% and the Liberal Democrats 7%. Clearly, there had been a lot of movement during the campaign.

The Conservative prime minister at the time, Theresa May, inherited a healthy parliamentary majority but then gave one of the worst campaign performances ever seen. She offered little on Brexit, the biggest issue of the day, and surprised everyone, including her own ministers, with a policy on social care that was communicated so poorly, she had to u-turn on it during the campaign, while also insisting that she hadn’t.

Can the tide turn in 25 days?

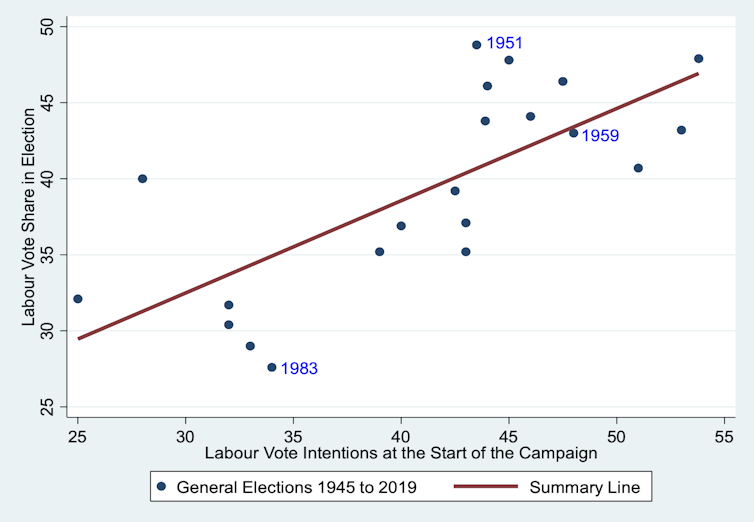

To get an idea of how important campaigns are in general elections, we need to look at them over a long period. The chart below shows the relationship between Labour voting intentions at the start of each general election campaign, and the share of the vote for the party in the subsequent election. It covers all 21 contests since the end of the second world war.

How Labour vote intentions change during election campaigns

The summary line slopes upwards, indicating that when Labour is doing well in voting intentions, not surprisingly, it also does well in the election itself. The correlation between the two is quite strong (+0.73), which means that a lot of the electoral support for the party already exists before the campaign starts. The summary line provides a measure of pre-campaign support that is not related to what happens in the month or so of the campaign.

The 1959 election stands out in the chart because it sits right on the summary line. This means the campaign that year had little or no influence on the outcome. The result, a third consecutive victory for the Conservatives, was wholly predicted by pre-campaign support.

In other words, deviations from the summary line tell us if the campaign was a success or a failure.

When an election appears below the summary line, it means the Labour party did much worse than predicted, indicating that their campaign failed. This happened in 1983, when Labour had an unpopular leader, Michael Foot, and was challenged both by Margaret Thatcher, who was in power at the time, and by the newly created alliance between the Liberals and the Social Democratic Party, a breakaway group from the Labour party, founded in 1981.

When an election appears above the line, it means the result was a lot better for Labour than had been predicted. This happened in 1951 when Labour won close to 49% of the vote, its largest share in the whole post-war period. At the time the election was called, polling had suggested it would win 44% of the vote.

That election was particularly interesting because Labour won more votes than the Conservatives but lost the election, because it ended up with fewer seats. The postwar Labour government had many achievements, and its loss of seats in the general election of 1950 mobilised support for the party in the 1951 election. However, this support was geographically concentrated enough to give the Conservatives the advantage, so Labour ended up in opposition.

Want more election coverage from The Conversation’s academic experts? Over the coming weeks, we’ll bring you informed analysis of developments in the campaign and we’ll fact check the claims being made. Sign up for our new, weekly election newsletter, delivered every Friday throughout the campaign and beyond.

If the 2024 campaign fails to move the needle, the Conservatives can expect 23% of the vote to Labour’s 43%, as this is what the poll of polls told us on May 25, a few days before parliament was dissolved to kick off the campaign.

At the moment, however, it seems the Conservatives could do even worse than that, if early signs of the campaign are any indication. It started badly for them with Sunak’s election announcement being drowned out by rain and protesters, and his first policy proposal, national service for 18-year-olds, derided as “bonkers” by former military leaders.

If the pratfalls in the Conservative campaign continue, they could well end up below their own summary line. Sunak surprised everyone by calling the election earlier than expected. Could this be because he has essentially given up, and wants to get back to Silicon Valley as soon as possible?

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.