After “We Stray” by Antonia Showering, a British artist born in 1991, was sold for £239,000, six times its low estimate of £40,000, attention turned to “Moi aussi je déborde”, an abstract Rococo canvas by the 32-year-old wunderkind Flora Yukhnovich. A display board lit up with bids from around the world as the painting’s value jumped, finally going for £1.7mn, almost seven times its low estimate.

The atmosphere was calmer in March for Yukhnovich’s solo show at the Victoria Miro gallery in Islington, north London. Visitors to the white-walled space could view (but only view) work by the artist, who graduated from the City & Guilds of London Art School in 2017. Another of her paintings sold for £2.25mn at Sotheby’s last year, but the lucky acquirers of these ones did not pay millions.

The gallery’s prices for works such as “Maybe She’s Born With It” and “She is Beauty and She is Grace” were between £100,000 and £350,000 each — astounding bargains by comparison. When I asked if I could buy one, the reception assistant replied politely that all of them had been sold. He did not say so but it would not have made a difference had I arrived on the opening day with the money in hand: they were not meant for the likes of me.

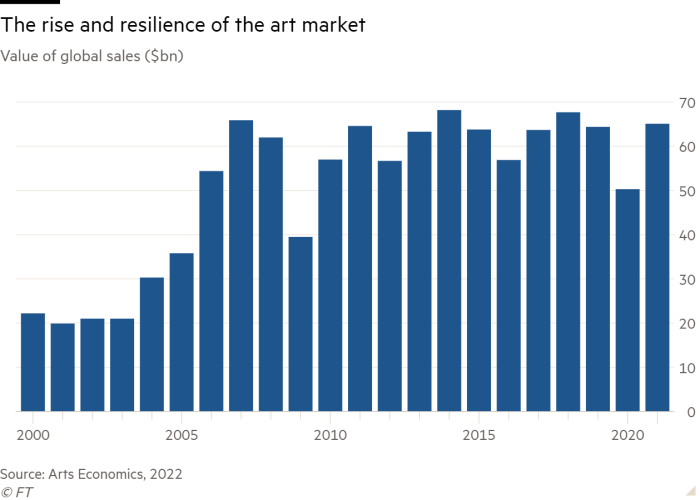

Behold the weird economics of the top tier contemporary art market. The $65bn market has bounced back sharply from the pandemic, as collectors have thronged to fairs such as Art Basel again from Europe, the US and Asia. But the surge of global wealth has unleashed speculation in the works of a few coveted artists, and desperate efforts by major galleries to contain it.

A gulf has opened between the auction market and primary sales at top galleries, with the most valuable and sought-after works being sold privately at below auction prices, but only to an inner circle. Outsiders to the club have little chance of buying one, no matter what they are prepared to spend. Access is reserved for institutions such as museums, or the gallery’s favoured collectors.

The idea is to control prices, and to block short-term speculation in an artist’s work by “flipping” — an impatient collector buying a work and making a profit by putting it up for auction quickly. It is intended to benefit artists, who gain little from any secondary sales and whose reputations can be damaged when the speculators move on and their prices deflate.

For most artists, it would be a luxury problem — they often struggle even to make a living, while smaller galleries do not need to ration access. But even at the top end, there are growing questions about whether such price control is the right way to protect artists. Perhaps the market should be opened up radically, with artists holding stakes in works and profiting each time they are sold. Instead of trying to stop speculation, they should ride the wave.

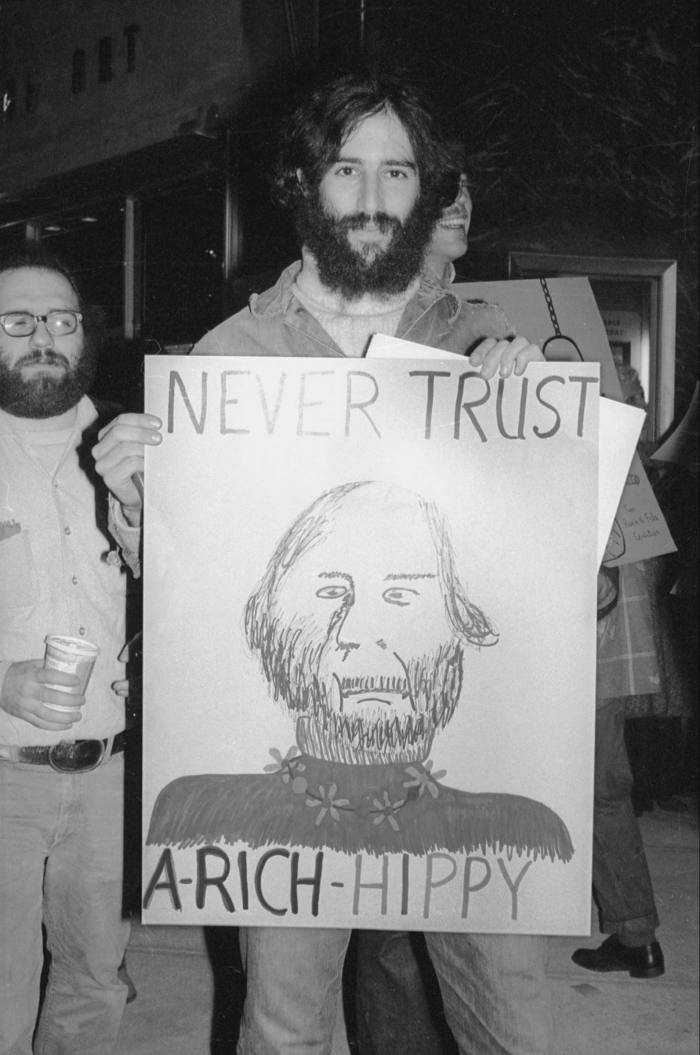

At the dawn of the contemporary art market, when auctions of work by living artists such as Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns started to become financial theatre, there was a pivotal encounter. The New York taxi entrepreneur Robert Scull put his art collection up for sale in 1973 at Sotheby Parke-Bernet, an event that was headlined “Profit Without Honor” in New York Magazine.

It included a work by Robert Rauschenberg that Scull had bought from the famous gallerist Leo Castelli in 1959 for $900, which fetched $85,000. Rauschenberg confronted Scull angrily at the end of the evening. “I’ve been working my ass off for you to make all that profit,” he said, in a clash captured on film. Scull replied that the artist should be happy because his work was suddenly worth more.

By today’s standards, there was little to complain about: Scull was hardly a flipper, having owned the painting for 14 years. But Rauschenberg’s central complaint was true enough: the profit on the auction sale went solely to the seller (after the auction house fees). An artist typically gets about half the money from the initial sale of a work at a gallery, but little or nothing after that.

Price surges have affected many artists over the years, including Peter Doig and Oscar Murillo, but have recently been intense. Interest has focused on young women such as Yukhnovich and Anna Weyant, a 27-year-old whose work “Summertime” was sold by a gallery for $12,000 in 2020, but fetched $1.5mn at Christie’s in May. Work by some black artists, including the Ghanaian painter Amoako Boafo, has also escalated in price.

“Something extraordinary has been going on. I went along thinking I was doing a young artist a favour and it was sold out by the time I got there,” says one London collector who attended Showering’s show at the Timothy Taylor gallery in January. Roman Kräussl, a finance professor at the University of Luxembourg, says “there has been way too much liquidity in the market. We have never seen emerging young artists getting pushed up so strongly.”

These prices have been driven by a limited supply of work by a few artists whose work has become fashionable, and by high demand. Young collectors who became rich by starting up companies or trading cryptocurrencies have started competing with established collectors. Activity surged last year, with the value of the global market rising 29 per cent; the art world is now waiting nervously for this year’s financial downturn to hit the market.

Concern about artists missing out led the EU to introduce an artist’s resale right in 2006, giving artists a share of up to 4 per cent of secondary sales, but the payments are capped at €12,500. “Artists lose control when they sell their work. Their reputations may grow as it is bought and sold, but they do not necessarily gain a direct financial benefit,” says Amanda Gray, a partner at the law firm Mishcon de Reya.

Young artists’ careers can also be badly disrupted by a burst of speculation. Price volatility is routine in most markets but stability is prized in the art market. “Someone will always buy wheat or orange juice even if the price has fallen but no one wants an artist that others aren’t interested in,” says Marion Maneker, editorial director of LiveArt, an online art marketplace.

Lucien Smith is one artist who was affected. He was among the “zombie formalist” group of US abstract painters who briefly became fashionable a decade ago and his paintings sold for well above auction estimates but, when they fell again, he struggled to regain his footing. “A lot of insiders got a great opportunity to buy my works and immediately flip them, with no incentive to further my career,” he recalls.

A sudden flurry of demand can also put artists under psychological pressure: it is distracting to try to paint or sculpt amid a financial frenzy. “Artists want collectors to focus the conversation on art itself, not on its financial value. In a volatile, heated crucible like an auction house, that gets blocked out by money,” says Matt Carey-Williams, Victoria Miro’s head of sales.

It is less traumatic for galleries, which invest heavily in building reputations, with Gagosian and Hauser & Wirth putting on exhibitions around the world: higher prices represent a return on the investment. But they have an incentive to damp speculation: their profits are maximised when artists’ prices grow steadily and smoothly over long periods.

Above all, they try to avoid alienating their collectors by selling an artist’s works at one price, only to cut it later. “The most striking phenomenon of the price mechanism for contemporary art is a taboo on price decreases,” says one study of galleries in New York and Amsterdam. “They don’t want price volatility, especially not downwards,” says Olav Velthuis, the author of the study and a professor at the University of Amsterdam.

If prices fall, it punctures the aura they have constructed around their artists’ work. “Galleries have perfected the art of creating an extraordinary mythology around what they sell, and are not just playing a short-term, profit-maximising game. It is rational sometimes for them to take less up front,” says Noah Horowitz, head of gallery and private dealer services at Sotheby’s.

This is why Yukhnovich’s work was sold for well below her auction prices, but only to institutions or collectors that can help her reputation by giving their imprimatur. The ideal for any gallery is for artwork to be bought by a museum such as Tate and placed on display. “We always privilege institutions because the work will be in a place where the public can see it. That is the golden chalice,” says Carey-Williams.

Short of this, they favour influential buyers who already have valuable collections and may be on boards of big institutions. “It is nearly impossible to get access unless you are an institution or a huge collector,” says Sibylle Rochat, a London-based art adviser. Telling other clients that she cannot obtain work for them involves “managing a lot of disappointment”.

Even when a collector is offered a prized painting, it comes with restrictions against flipping. Galleries and artists often ask collectors to sign non-resale agreements, typically pledging not to sell a work within three to five years, and to offer it back to the gallery first. It is unclear how legally enforceable such agreements are — Gray says that none has been tested in a UK court — and they tend to be kept quiet in the notoriously opaque private sales market.

One deal came to light last year in a US legal case involving the collector Michael Xufu Huang, who in 2019 bought a work by the artist Cecily Brown for $700,000 from Paula Cooper, a New York gallery. Huang paid a settlement to the gallery after it discovered that he had resold it to another collector in breach of the three-year holding period set out in a sale agreement (it was auctioned at Sotheby’s for £2.9mn in March).

Galleries also deploy other strategies to manage intense short-term demand for top artists, including the US practice of “buy one, gift one” in which collectors are asked to buy two works, but only to keep one. The other is donated to a museum or institution to try to bolster the artist’s reputation, although some institutions resent being targeted in this manner.

Another common tactic is telling collectors that if they want to obtain paintings from one artist, they need to buy work by others the gallery represents. It distributes demand but it also involves forcing collectors to acquire work they do not really want and may soon resell. That raises an awkward question: who are the gallerists really serving: artists or themselves?

To buy the Brown painting, Huang had to sign an agreement with the gallery noting “the great harm that speculation on artworks” inflicts on both artists and galleries, but that does not strike everyone as iniquitous. “It is one of those shibboleths that make no sense. Collectors should honour agreements but there is nothing wrong with buying and selling art and there never has been,” Maneker says.

Rauschenberg was right: he sacrificed a lot before his 2008 death by not being in a position to profit from auction sales. If he had retained a 10 per cent stake in paintings sold by the Leo Castelli gallery between 1958 and 1963, he would have made 50 times more the first time they were auctioned than from taking his split of their original sales at the gallery in cash.

This figure comes from a study of artists’ returns by Kräussl and Amy Whitaker, a New York University professor, who argue that artists should treat their work more like an investment than an asset they can only sell once. “Not everyone will get rich but at least let’s give artists some monetary power. Otherwise, they are wholly dependent on galleries and collectors,” says Kräussl.

The notion of artists becoming stakeholders in their own work is not novel: it even predates the Scull auction. Seth Siegelaub, a New York art dealer, and Robert Projansky, a lawyer, drafted a model agreement in 1971 to secure artists 15 per cent of any increase in price each time their work was sold. But it never caught on, partly because it was impossible to enforce.

Non-fungible tokens have made it easier: physical artworks can have digital ownership certificates that record any minority shareholders and trigger payments every time the works are sold. Having been burnt once by speculation in his paintings, Smith has now joined Lobus, a US-based start-up that uses NFTs to allow artists to retain fractional ownership of paintings at the initial sale.

Sarah Wendell Sherrill, a former Christie’s executive who is co-founder of Lobus, argues that artists should treat their work like founders of technology companies, who can attract outside investment without having to give up all their equity. “Artists are taking on the role of founders and saying: ‘I will control the sale of my work.’ Leverage is shifting faster than we expected.”

After a surge of interest in NFT works of art such as Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 5000 Days”, which sold for $69.3mn last year, the digital NFT market has suffered a heavy reversal. But Wendell Sherrill says it has already helped to encourage a different attitude to speculation. “NFT artists have encouraged trading in their work because they are cut into the economics,” she says.

Ultimately, young artists may find it hard to look the gift horse of speculation in the mouth. The model of sacrificing short-term returns to entrench longer-term careers only pays off if their work keeps selling. As Stavros Merjos, a Los Angeles-based art collector, explains, it is a brave bet because they have to keep attracting interest in a market where there is always someone new.

“Think about how many rock bands were successful in their twenties and ended up making good music into their seventies. The answer is very few. You might end up being an artist like Gerhard Richter, who just built and built, but you also might not,” he says. When the art market reconvenes in the autumn, the recent frenzy may already have subsided; if so, some will miss the days of rampant speculation.

John Gapper is the FT Weekend’s business columnist