"Alex kept saying 'I’m not a paedophile', but they took him into custody"

Vivienne scrapes her blonde hair into a high ponytail before inspecting her face in the mirror. Her skin looks parched, and the whites of her eyes are streaked with red. First, she rubs moisturiser in, then smears foundation into her forehead and cheeks. Next, concealer over her spots, pressed in with her forefinger. Her eyedrops spill over her lower lashes. She applies two coats of mascara. It’s like she’s colouring herself in. Her eyes almost look rested now. On the dresser is a photo of her on her wedding day, with her mum.

Every morning, Vivienne cycles with her daughters to school. It’s a good 10 minutes, mostly downhill. Yesterday, a woman in a SUV pulled up at an intersection where they had stopped and rolled down her window.

“I hope he gets a life sentence,” she shouted.

Did she not care that Ines and Ellie were in earshot? Vivienne mouthed fuck you, and they rode on. Before, Vivienne was a contained person. But now there was nowhere for her to contain anything because nothing was private anymore.

Vivienne’s friend Sadie said, “Stay home for a while, people will come around,” but Vivienne wouldn’t give in. They’d done nothing wrong.

Six weeks ago, two police officers came to arrest Alex, her husband, for downloading images of children. Alex kept saying “I’m not a paedophile”, but they took him into custody and removed all the computers from the home, including Vivienne's personal laptop. They would do a deep scan.

The mist has come right in off the harbour and is settling into the far pockets of the garden. She can just make out the playhouse. She puts her slippers on and goes into Ellie’s bedroom. Ellie has turned her bed into a fort, using a chair and some rugs. Her rag doll Trixie is on the floor – so well-loved she has lost an eye.

Alex was questioned for twelve hours, then eventually they ushered Vivienne into a horrible concrete room. And they said, “Alex has got something to tell you.” That’s when he confessed, if you could call it that.

He said, “I’ve seen some things.”

Across the hall from Ellie’s room is a smaller room, with a desk and a leather armchair, one of the ones that swivels. Vivienne doesn’t go in there, not anymore. That's where he sat to download and look at the images. After dinner most nights, with a glass of Jamesons.

“No, you haven't just seen things,” she’d said. “You went looking.” Her anger had gotten the better of her. This was what happened, wasn’t it? He’d gone looking for it.

There’s a screen between me and them. It's a virtual world.

How had he even started going to chat rooms? Her niece, Tara, second year at university, was now boarding in that room because, as Vivienne rather bluntly told the girls, it wasn't as though their father was going to be moving back in. There was a futon wedged beside the desk now. She could understand him becoming addicted to a thing, but it was very hard to understand him becoming addicted to that.

Ines had the room down the hall. She never picked up her clothes. The weekend laundry was always Alex’s job. At fourteen, Ines was worryingly childlike but had recently started using Vivienne’s eyeliner and become concerned about gaining weight. Ines was fair-haired like Vivienne, but, as Alex had often noted, very much his child around the eyes. Not anymore.

Recently, Ines had been using the trauma caused by her father’s sex offending to get out of doing things.

“I’m fine. Just leave me alone.”

While it hurt that Ines wouldn’t confide in her, Vivienne was worried she would become one of those rich kids with no focus. Vivienne had promised she could continue to see her father – she was connected to Alex in a way that Vivienne wasn’t, in a way Vivienne couldn't explain other than by blood. Vivienne wouldn't even have a photo of him in the house.

Vivienne stands at the sink, rinsing plates, putting them into the dishwasher. Dinner crumbs on the table, Ines’s plate untouched. She pictures Alex sitting across from her, clean shaven, working on his laptop. They’d enjoyed a glass of wine after work, talking about things that mattered, or didn’t. A past life.

Their marriage had been in trouble before, after Ines was born. Vivienne ignored it for a time, and it got better, but then she had Ellie and it got worse. Maybe it was another baby or maybe it was something she did or maybe it was nothing at all. She remembered saying it.

“I’m not happy.”

He hadn’t asked her what she was unhappy about. She had watched his mouth and his dark eyes. Her mother had often said that Alex had beautiful eyes. Wasted on a man, she’d said. After that, everything had built and built and then spilled over. But of all the things in the world that were her fault, this didn't seem to be one of them.

Alex was released on bail, and they’d driven home. A week later he packed and moved out. 170 kilometres away, to a caravan on his cousin's farmland. Before he left, she pushed for details, asking about the ages of the children.

“I can handle it,” she said.

He said he’d seen pretty much everything. Which came as something she couldn’t comprehend, really. As far as she knew, they were a happy, ordinary couple. What was wrong with her? Just stick with what was right, what he should have been looking at, which was her.

She turns the dishwasher on, and goes down the hall to check on the girls. It’s important there are no gaps for thinking or spare moments for thoughts to slip in. But the thoughts come anyway, ramming into one another before she can ward them off. And then they are there whether she likes it or not. She's always known how to get on with things, how to keep busy. But she doesn't know how to get on with this. He’s ruined us, Vivienne thinks, … Shouldn’t Tara be back by now? She was a grown woman – but Vivienne can’t help feeling responsible, with her under their roof. She’ll call Tara and she’ll answer. Things will be fine.

Lynne, her sister-in-law, called her as soon as they heard.

“I'm so sorry,” she said.

Family came before everything. All those horror stories of being disbelieved by their families: that wasn't happening to her. I thought you blamed me, Vivienne didn’t say. She asked about them, their trip to Rarotonga. The food so fresh, Lynne said, sunsets like you’ve never seen. This wasn’t why she called. She wanted to know why Alex did what he did. As if Vivienne should know! Vivienne wished she could tell her, beyond the obvious: He didn't even like sex that much with me. She wasn't sure where to begin. Maybe Lynne could help by telling her what it was they already knew?

Thinking too much muddied the waters. Last year, Vivienne ran a half marathon with Sadie and a few others from the neighbourhood. Or was it two years ago? She remembered she pumped and dumped, so Ellie was being weaned. They’d taken over Sadie’s bathroom the evening after the race, drinking wine while they did their hair and make-up. Intoxicated with the lack of responsibility. At the party, Iain from number thirty-seven tried to engage her in a conversation about the ecological damage they were doing to the world. Iain was Ines’ friend Sage's dad. Vivienne wasn’t interested in why she’d done it. It might have been sleep deprivation. Or the feeling that if she didn't make something happen, nothing would happen. It was an unremarkable fuck. Alex had always occupied the prime position in her life.

“David and I were talking,” Lynne went on. “You don’t think he ever ... nothing inappropriate with the girls, do you, Vivi?” What had been a flicker became something more steady. Vivienne saw the girls and Alex bouncing on the trampoline: piling up on the mat, laughing.

“We don’t think Alex is a terrible person, do you? Just somebody in pain with nowhere to place it,” Lynne says. Vivienne replayed the trampoline pile up in her head, concentrating on where he put his hands, but it was impossible to tell what was memory and what her mind was making up.

“Listen, it’s Ellie’s bath time, I'll have to go. Lovely to hear from you.” Bath time. Vivienne hadn’t really been thinking of speaking those words. Often, she thought about what the most wrong thing to say or do would be, in any situation. Yes, she owes them a visit. She must do that soon.

The news had spread fast. It was the kind of neighbourhood that got together for Guy Fawkes and held a sausage sizzle for the children. And Halloween was an event that even Vivienne and Alex looked forward to. Most of the street refused to speak to them anymore. Some neighbours were better at hiding their disgust than others, but it was still hard to go walking. Some people had a way of not looking. Did they hold her responsible in some way? Did they see her as immoral, by way of association? She started going running after dark, leaving Ines to read bedtime stories to Ellie.

Vivienne steps outside, lighting a cigarette. The second time today, although it’s getting late. She tries to go outside at least twice a day. Otherwise, she feels trapped.

It was Alex’s idea to move here, near the best schools. She was just getting used to it when all this happened. Before, she wouldn’t have called herself naive. She knew about the world, her head was on straight. But now her voice locked in her throat when she thought about what other people might know, that they might be repulsed by the sight of her. Her good and quiet husband. It was a terrible version of himself, he’d said. Like he’d told himself a story so that it became something he could live with. And Vivienne had laughed and said, You have no idea. She didn’t want a part, or the children to be any part, of it. They’d get bullied. She pictured it – striding across the school playground, grabbing the kid and shaking the hell out of him. Ines was only fifteen and Vivienne could see her struggle to make sense of it all. It was impossible to explain it, but the reasons for her dad leaving were important to Ines, so they had to try.

Vivienne stayed away from the trial, but it made headlines. Deviant sexual interests, the judge concluded, before reading out the sentence. Alex’s career was finished. Nothing was found on his work computer, nothing they could pin on him anyway. You had to wonder, all-girls high school, his preferred demographic. Chocolates at the end of term, thank you cards. Overworked, stressed, and perhaps that had led him to make bad decisions that had adversely affected the people around them. Sorry girls, your father has failed you.

Vivienne flashes the headlights. As soon as Ines is inside the car, Vivienne feels lighter. All morning, she swum in their pool and worked on a story for the magazine she edited. Ellie was at daycare.

Ines does up the seatbelt, across the beginning of boobs and Vivienne starts the car. She was, overall, fine with the arrangement, which was that once a month, Ines would meet her father here, at this always busy cafe.

“He cries every time,” Ines says as she gets in the car.

Probably fake tears, Vivienne thinks.

“Starting over has been hard on his own. I hope he meets someone soon.” Ines scrolls through her phone.

“Do you think that’s realistic, after what he’s done?” Vivienne asks, pulling out into the traffic. “Surely he’d have to tell that person.”

Ines has developed this irritating habit of asking questions and then getting bored halfway through, asking another one, and then giving up. She’d been talking about her father’s sex crimes a lot recently. She’d mentioned it at the mall and heads had turned. Vivienne asked quietly that she lay off but Ines had waved her mother’s protest away.

“You’re in denial, aren’t you?” Ines had said, louder still, “You’d rather not face up to this stuff.” Vivienne had walked into a store, away from her. She wished she’d been able to protect the girls. Gossip got around fast.

They are half-way home, Ines still scrolling on her phone. “Hon, it’s hardly my stuff to face up to, quite honestly.” Somehow, Ines seems to hold her mother responsible for what had happened.

“Well, everyone has a past, Mum,” Ines says. “He’d just have to meet someone who could understand that there's more to him than his crime.”

“Very few people would, Ines ...” Vivienne brakes to make sure she is only five kilometres over the speed limit.

“Just because you’re uncomfortable. . . makes you think that other people would be equally as uncomfortable.”

“Sweetheart, he wasn’t just looking at naked ladies.” The car stalls a few times up the hill, but Vivienne eases it along, making a mental note to book it in for a service.

“Yeah, I just think it’s more complicated than that – he was unhappy. And not thinking.”

“Perhaps you don't quite understand the idea of ... taking responsibility?” Vivienne says. “For your own actions, I mean we are in control of what we do.”

“You don’t really understand depression. I can join the dots which make a lot of sense to me ...” Ines trails off.

“What do you mean, join the dots?”

Ines stares out the window and doesn’t say anything.

“What, you can sort of imagine how that would happen?”

“I can see how it might happen.”

“You sound very ... forgiving, Ines. You know, it's different for me – you’re flesh and blood. It's a different ... betrayal, really.”

“Depression isn’t logical. It’s just a collection of atoms and it’s possible to change your thought patterns. You shouldn’t blame someone for being depressed.”

“There’s nothing wrong with being depressed, you’re missing the point.” An urgency has crept into Vivienne’s voice. “Isn’t it about values? Doesn’t it reveal something about your father’s character?” Vivienne knows she is on the cusp of saying all the wrong things so doesn’t particularly mind when Ines interrupts.

“You could start by asking some questions.”

Vivienne grips the wheel. She doesn't need Ines to tell her that. If Alex was here. But he wasn’t. He’d caused this bloody mess.

The road is narrow now, full of sharp turns and hills. The Pacific stretches out below them. How good it would be to be floating in it, weightless and unafraid. She has no real memory of the drive from the cafe.

“Sweetheart, I don’t think you comprehend the weight of bringing you and Ellie into the world.” While a part of her knows she drove safely, she can’t recall intersections or lane changes, or how long they waited at such and such. The conversation was unnerving.

“There you go again,” Ines says.

“I know I’m always saying it, and you get tired of me saying it.” Home is three streets away.

“Go ahead Mum – ask the question of the day, everyone else is.”

"Oh, all right. Fine." Alex always knew what should be done and how. Fuck Alex. “There are some things I can’t articulate because of what they might mean.”

“That makes no sense.”

Vivienne opens her mouth, but no words come out. Neither of them speak. When they pull into their driveway, Vivienne feels like the world has ended around them, but they don’t know because they are inside the car. It isn’t a safe place.

“I can’t bear the thought of anyone hurting you.” There, she’d said it. She owed her daughters that much.

“You’re kidding, right?” Ines laughed. “Oh. You’re not kidding.”

Ines told her mother that recently her routine had been wake up, throw up, go to school, come home, throw up, sleep.

Vivienne leaned across and put her arms around Ines, and her shoulders tensed, but she put her head on Vivienne’s chest. The luck of it. It was a safe place, after all.

Vivienne goes to Sadie’s, and they sit by the pool, drinking beer while they watch the kids swim. Vivienne is still uneasy in public – the school gate, the coffee circuit.

“Does anyone even speak to him?” Sadie asks. “Monster,” she says, under her breath. She takes a swig of beer.

“Can we not talk about him?” Vivienne says. They talk instead about Tinder.

“Are you sure you’re ready?” Sadie says.

The frequency of sex had diminished when they became parents but she and Alex had a lot of sex in the early days. It was high quality. Nothing outrageous – Alex had seemed straight up – but he knew what she liked and how to get her there. He was sexually confident, and this appealed to Vivienne. There were no doubts.

“What can I say?” Vivienne says, scrunching her hair on one side. “I know what I want.”

“I think you’ve changed,” Sadie says.

Vivienne looks at her friend. She promised Ines she wouldn’t tell Sadie. She wants to tell her yes, she’s changed. Everything has changed. Ines is at home watching TV and probably eating ice cream to throw up later, and Vivienne is struggling to think of a time happier than this. They could talk to someone about that. They were intact.

The following week, Vivienne requests the police file. She needs to try and understand what has happened to their lives. Maybe by seeing it on a page, she can restore a kind of order in her mind. Join the dots, or so she hopes. But here is the thing – without this report in front of her, she might doubt that any of it occurred. There are aspects of it that she thinks she might even have made up. The best she can do is be there when the girls needed her.

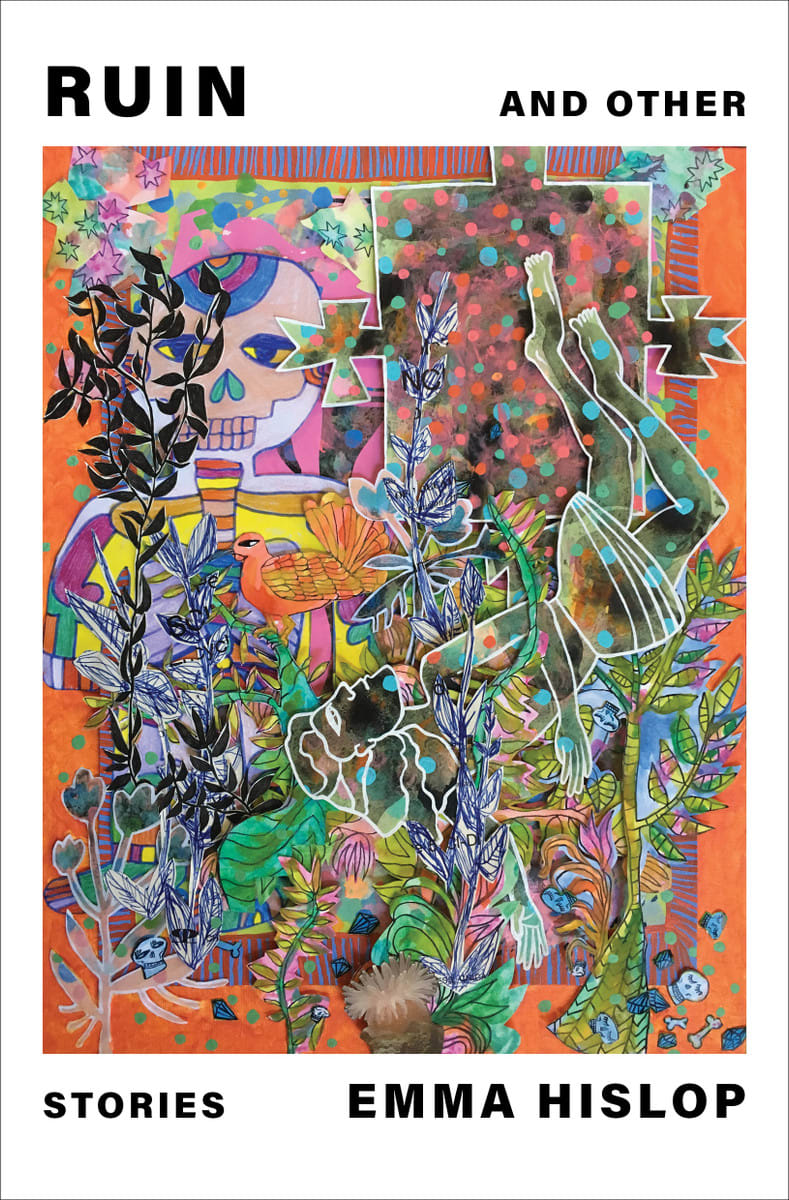

Taken with kind permission from likely the best story collection of 2023, Ruin and other stories by Emma Hislop (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $30), available in bookstores nationwide.