A party was already in full swing when Patricia Krenwinkel, 19, entered her sister’s apartment in Manhattan Beach, California, on a cool September night in 1967. That little surprise — a spark of social levity after a long day of work — would begin her bloody path toward becoming the longest-incarcerated female inmate in the state’s history.

Krenwinkel had been living with her sister while working a job as a secretary. A year prior, she was attending a Jesuit college in Mobile, Alabama. In her teens she taught the Catechism, and, after a life of bullying due to her weight and an endocrine condition that caused her to grow excessive body hair, thought that perhaps she could find purpose serving as a nun.

After a single semester, that dream crumbled and she moved back west to live with her sister. Though she managed to lose weight, the self-loathing borne from years of feeling ugly and unwanted held firm.

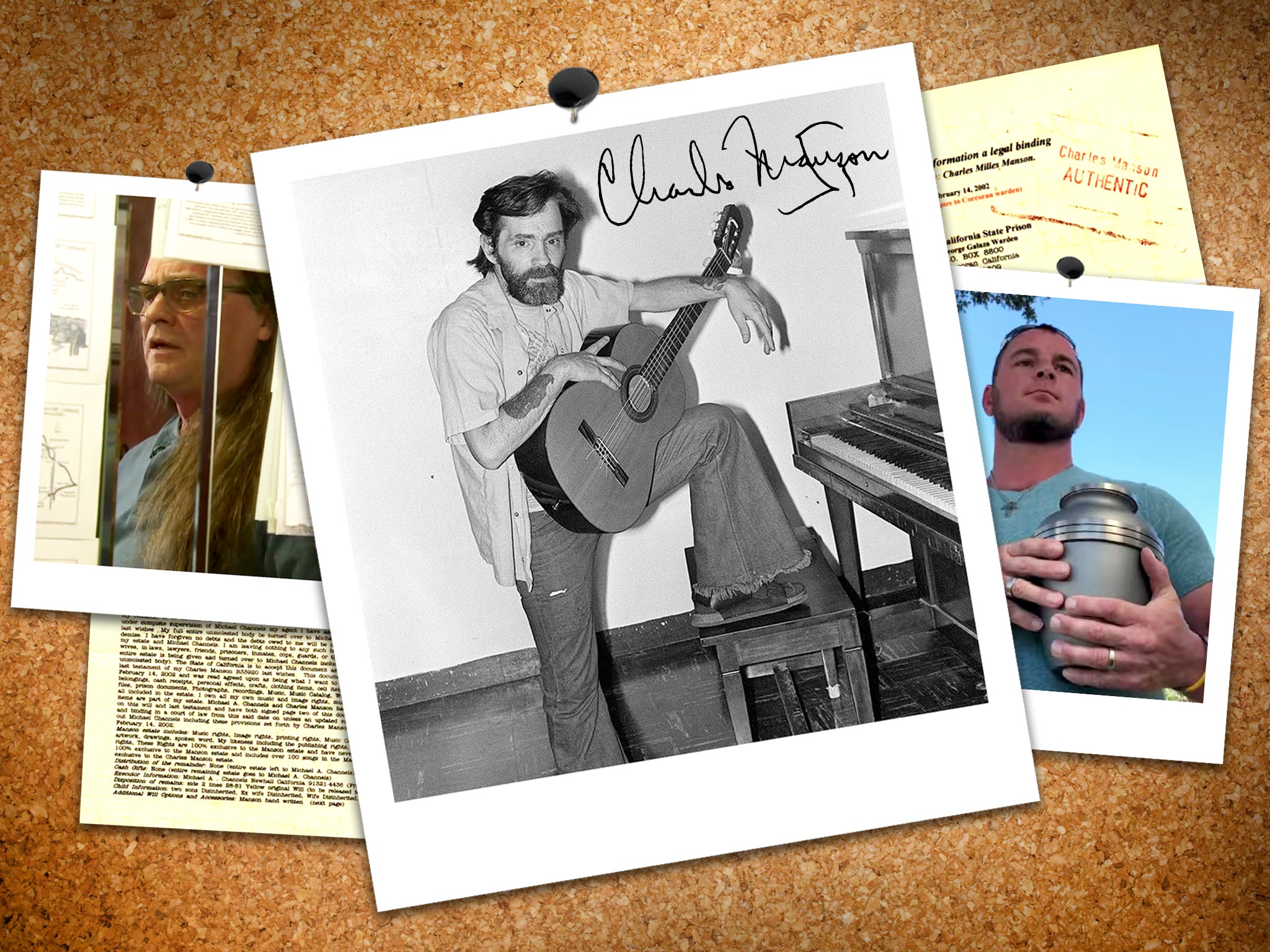

Then, she met one of her sister’s party guests – a long-haired guitar player named Charles.

By the end of the evening, Krenwinkel and her newfound paramour, Charles Manson, had slept together. Krenwinkel says Manson was the first man to tell her she was beautiful. She was ready to follow him anywhere, and she told him as much. He held her to her word.

Whether Krenwinkel truly believed in Manson’s plan to stand atop a broken America as a king following a devastating race war of his own making, or just in the man who made her feel special, is irrelevant. The end result was the same — seven innocent people died by the hands of Krenwinkel and the other members of the Manson Family cult.

On 14 October, California Governor Gavin Newsom blocked a parole recommendation for Krenwinkel, now 74, who was arrested on seven counts of first degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder in December 1969. In 1971, after a nine month trial, Krenwinkel was convicted on all counts and sentenced to death.

CNN reports that the governor rejected the parole board’s recommendation after determining that Krenwinkel “currently poses an unreasonable risk of danger to public safety.”

“After an independent and thorough review, the evidence establishes that Ms. Krenwinkel is not suitable for parole and cannot be safely released from prison at this time,” he said in a statement.

Though she initially maintained a ferocious loyalty to Manson, distance and isolation in prison corroded her allegiance and Krenwinkel began to focus on her own enrichment. She joined both Narcotics and Alcoholics anonymous groups and began pursuing an education, eventually completing a bachelor’s degree in Human Services from the University of La Verne, according to court records.

During her more than half-century of incarceration, court records show Krenwinkle has assisted in the training of service dogs and has taught fellow inmates how to read. Her behaviour in prison has been spotless.

She has also accepted her role in the murders.

"I don’t believe there are any words to say what I have done. I take full responsibility for the death of every person in both those residences," she said during a 2004 parole board hearing.

A decade earlier, she appeared in an interview with Diana Sawyer and said the murders haunted her daily.

"I wake up every day knowing that I’m a destroyer of the most precious thing, which is life; and I do that because that’s what I deserve, is to wake up every morning and know that," she said. “That was just a young woman that I killed, who had parents. She was supposed to live a life and her parents were never supposed to see her dead.”

However, it was still Krenwinkel who chased down 26-year-old coffee heiress Abigail Folger in August 1969 and stabbed her over and over — 28 times in total.

It was still Krenwinkel who helped fellow Manson Family members kill Leno and Rosemary LaBianca the next evening. She helped carve the word "war" into Mr LaBianca’s corpse. She used the victims’ blood to paint the words “healter skelter” [sic] and "Death to Pigs" inside their home.

During a previous parole hearing in 2016, Debra Tate — the sister of actor Sharon Tate, who the Family murdered in the summer of 1969 — launched a Change.org petition to ensure Krenwinkel was kept securely behind bars.

“Society cannot allow this serial killer who committed such horrible, gruesome, random killings back out, and I am asking for your help to let the parole board know you do not want to see her get early release,” she wrote in the petition.

Krenwinkel was recommended for parole, but then-Governor Jerry Brown blocked her release. She was told she would have to wait another seven years before she could again try to return to society.

Seven years passed. In May 2022, Krenwinkel was, for the second time, recommended for release by a parole board.

Fifteen times Krenwinkel has sought parole, and 15 times she has been denied.

“Ms. Krenwinkel was not only a victim of Mr. Manson’s abuse. She was also a significant contributor to the violence and tragedy that became the Manson Family’s legacy. Beyond the brutal murders she committed, she played a leadership role in the cult, and an enforcer of Mr. Manson’s tyranny," Gov Newsom said in his recent review. “While Ms. Krenwinkel has matured in prison and engaged in commendable rehabilitative efforts, her efforts have not sufficiently reduced her risk for future dangerousness."