Shannon Burns’ memoir Childhood begins with an epigraph from Leo Tolstoy’s book of the same name:

The happy unrecoverable days of childhood! How could I not love, not cherish its memories? They have lifted up and refreshed my soul and served as the source of its finest pleasures.

The South Australian suburban childhood explored in this memoir is far from idyllic. Burns’ early life was one of disconnection, neglect, violence and poverty.

Review: Childhood – Shannon Burns (Text Publishing).

When he started writing Childhood, Burns was a literary critic and writer, who had taught at university for a decade. He had been experimenting with memoir for a while. Earlier versions of sections of this book have been published in various periodicals.

Given the neglect he experienced, Burns has few records of his life before the age of six, and sketchy memories – potentially unpromising material for a memoir. He admits that “the inner archive is almost blank”. Yet he retains a “tiny window of flickering memory” that he draws on extensively.

Frequently misrecognised as somebody from a middle class background, Burns claims that people tend to assume he went to a nice private school and “enjoyed a solid measure of nurture and support”. Fellow students or new colleagues have been shocked when he tells them about his childhood, invariably asking: “How did you go from that to this?” His answer is: “I knew how to forget.”

Burns describes his existence as “aberrant”, because it was based on a lie. His mother was in her late teens and father in his late twenties when they got together. His father’s story was that she told him she was pregnant to force him to stay in the relationship. Her pregnancy to a non-Greek man outside of marriage brought shame to her traditional Greek family. His yiayia “adored” him and his papou “endured” his presence, but they were not able to shelter him for long.

The setting for his early years is Elizabeth North – a working class suburb 20km north of Adelaide also associated with Jimmy Barnes’ dysfunctional childhood, as depicted in his memoir Working Class Boy. As a child, the only person Burns knew with a job was an uncle, who was a security guard. Most members of his family were on benefits, rendering them “human waste” in the eyes of his unsympathetic working class neighbours.

The memoir begins with a vignette from when he was four or five: a recollection of his backyard with an almond tree, prickly weeds and a cast iron fence. He sees his mattress drying on the back porch with a frisson of shame, alongside a caged budgerigar called Pretty Boy who later died of exposure.

The boy picks a red shrub rose for his Mum to make a show of wooing her. Like the weather, she is unpredictable, blowing hot and cold, leaving him watchful and anxious. Her mental illness and lack of prospects contribute to her negligent parenting, including a remembered moment when he wakes up alone on a concrete floor with a bloodied face. He draws on hazy memories of being locked in his bedroom, not knowing whether his mother was home or not.

His time with his mother was punctuated with spells in other homes, where he is almost continuously hungry and unsafe. Sent to his father’s house in a stranger’s car in the middle of the night, he ends up staying there for a few years on and off. His father is depicted as an angry, underemployed young man, who taunts his son and has an unhealthy obsession with his stepdaughter. The young boy soon settles on a few clear truths: his father and stepmother don’t love him, don’t want him, and they are scary. He gathers from what his father tells him that “To love and need my mother was to be a fool.”

Distancing and form

Most memoirs are written in the first-person, though some contemporary memoirists take a more experimental approach. In her “form-bending” trauma memoir Homesickness, for example, Janine Mikosza deploys two voices, Jin and Janine, an interviewer and a memoirist, who visit Mikosza’s former homes together, showing how internal voices may both comfort and compete with one another.

Throughout Childhood, the narration switches from the first-person to the third-person. At times, Burns talks about himself as “the boy”, possibly as a more bearable way of handling distressing memories. It also implies that his experience is particular and shared by many children from the “welfare class”.

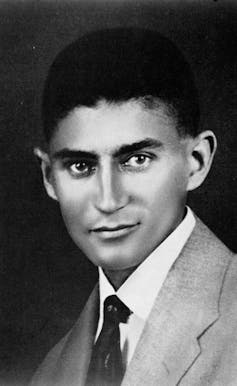

In the epilogue, Burns cites Franz Kafka’s story “A Report to an Academy” (1917), which features Red Peter, an educated ape, to illustrate his own feeling of being out of place in a university milieu:

I could never have achieved what I have done had I been stubbornly set on clinging to my origins, to the remembrances of my youth […] In revenge, however, my memory of the past has closed the door against me more and more.

For Red Peter, the price of becoming human is that it is a one-way trip; to return would involve skinning himself alive. This analogy might seem hyperbolic to some readers, but for those who have suffered trauma, the prospect of return may be impossibly perilous.

The story of Red Peter has been cited by J.M. Coetzee in his metafictional work The Lives of Animals, which takes the form of lectures delivered by his character Elizabeth Costello, signalling a link with the J.M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice where Burns is a fellow. With its generic title, Childhood also acknowledges its debt to Coetzee’s autobiographical trilogy Scenes from Provincial Life, especially the first two volumes Boyhood and Youth, both of which are written in the third-person, creating an ironic distance between the mature author and his younger self.

A way of being

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu used the term “habitus” to describe a person’s way of being in the world, understood as a product of their specific personal history. As a result of the trauma he has suffered, Burns develops an evasive disposition. Although he might look purposeful and striving, he argues that his real talent is withdrawal and redirection. He is able to focus his energies on one thing and let all other considerations float away, an ability that has been beneficial in his chosen career of literary scholarship. For Burns, reading is its own form of human connection and serves to regulate his emotions.

Rejecting the role of victim, Burns embraces a working class ethos, which is at odds with the welfare class existence that he’s born into. As he explains in his 2017 essay In Defence of the Bad White Working Class:

whenever I allowed myself to feel like a victim, I fell into paralysis and deep poverty; whenever I took pride in my capacity to work and endure, things got slightly better. One world view worked; the other didn’t.

When he drops out of school and works full-time at a recycling centre, Burns is surrounded by older damaged men, ex-prisoners and addicts. This unrelentingly dirty and repetitive work makes his hands bleed, but it also allows him to live alone, albeit without electricity for night-time reading.

After an ongoing struggle, he arrives at university and decides that a law degree is dangerous for somebody with his temperament: “the resentment was too strong and made me uglier than I hoped to be, so I gave up law as a precautionary measure.” By the time he became a tutor in literature, he had learned to “gulp down” his distaste and “concentrate on the words”, and the intelligence and industriousness of his students.

Near the end of Childhood, Burns reproduces an unsent letter to his mother which appears to be chillingly disengaged. He compares himself to a dog he encountered in foster care that ate its own shit, from sheer hunger. “Here is the real calamity”, he says to his mother,

the tragedy that keeps us apart: we’re characters in two different stories, and yours is a nightmare from which I am trying to escape.

Realising that she wants to reconnect with him, he asks her to “imagine” that her boy forgives her when the truth is that he doesn’t believe in forgiveness. Long ago, he taught himself how to live without his mother, and there is no going back.

Trauma memoirs are often hailed as “inspiring”, but I suspect Burns would refuse the designation. Instead, he emphasises the warping effects of falling upwards, bravely listing his own misdemeanours, such as bullying others at school and being a careless boyfriend as a younger man, along with his complicated feelings of complicity with his father’s perversion. The passages in which he describes his relationship with a teenage friend’s unstable mother make for excruciating reading.

As a survivor, Burns has an ingrained habit of expecting the worst. He is able to make himself numb when required and forgets painful moments easily. Reflecting on the demise of the boy who picked the shrub rose for his beloved mother, he remarks:

Perhaps there are people who can afford to be supersensitive beyond their middle teens, but he is not one of them. He lost years of his life in the name of strong emotion, paid for it with abjection.

Childhood recounts domestic horrors in a matter-of-fact voice devoid of self-pity, yet it is not without feeling. It offers a compelling view of Burns’ turbulent formative years from the perspective of a “dangerously contented” existence in another part of Adelaide. Thirty-five years after leaving Elizabeth North, Burns drives half an hour from his current home to explore it again. The journey feels like “crossing galaxies”. Surprisingly, instead of the painful moments, he recalls the fun of those days, experiencing a fleeting sense of “at-homeness”. Being in Elizabeth North again makes him realise that

the lost world is still there, close to the surface, and so is my childhood, if I only allow myself to see it.

Brigid Magner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.