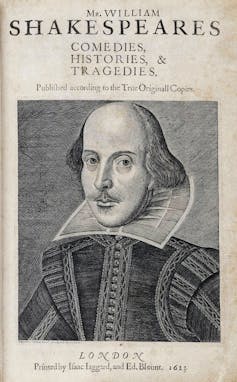

It has been 400 years since the publication of the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, a volume now known as the First Folio. Prepared by his fellow actors after his death, the book presented 36 plays divided into the genres of comedy, history and tragedy.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

Without it, 18 of Shakespeare’s plays that had not previously been printed would have been lost, among them Macbeth, Julius Caesar, Twelfth Night and The Tempest. No “friends, Romans and countrymen”, no “brave new world”, no “double, double toil and trouble”.

But what would really be different if this book had never been printed at all?

Most significantly, there wouldn’t be the cultural icon we know as “Shakespeare”. Those works that do survive would be scattered across numerous flimsy early editions, rather than gathered in this imposing and serious volume.

Without the weight – cultural as well as literal – of the collected edition, it’s possible few would care about these surviving plays. Something similar happened to other playwrights of the period, whose work was not given the authority of a collection.

We’d also have an idea of Shakespeare as more interested in histories and comedies than tragedies. Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar and Timon of Athens would be lost without the First Folio.

Since some of these early editions did not name Shakespeare on their title pages, the authorship of plays such as Romeo and Juliet, Titus Andronicus and Henry V would be uncertain. Conversely, title pages identify Shakespeare as the author of The London Prodigal (1605) and A Yorkshire Tragedy (1608), which most modern scholars do not attribute to Shakespeare. In part this is due to the fact that they are not included in the First Folio. Without it, the canon of Shakespeare’s plays would have decisively shifted.

This different canon would have prompted a different historical response. The convenience and ready availability of the First Folio as a repository for Shakespeare’s plays was a significant practical factor in getting him back into the theatres when they reopened at the Restoration of Charles II in 1660.

This large collection of Shakespeare’s works took up visible space on the shelf. Had he not come back into prominence at that important moment – and had the newly revived theatre looked elsewhere for their dramatic scripts – Shakespeare’s reputation might well have been permanently lost.

This article is part of our First Folio 400 series. These articles mark the 400th anniversary of the publication of the First Folio, the first collected edition of William Shakespeare’s plays.

If Shakespeare had not been revived in the later 17th century, it is hard to see how he would have become the national poet during the 18th. No statue in Poets’ corner, no arguments between the literary figures of the day about the best way to edit his plays.

David Garrick – the leading Shakespearean actor of the 18th century – would have had an entirely different career (as, in later periods, would other actors like Laurence Olivier and Judi Dench).

Shakespeare’s international reputation

This much-depleted Shakespeare would hardly have galvanised outrage about the sale of his Stratford birthplace in the 19th century.

Perhaps modern Stratford-upon-Avon would now simply mark its playwright son with a blue plaque (rather as Shakespeare’s writing partner John Fletcher is remembered in his hometown of Rye). There would be no birthday parade, no Othello taxi firm, no tourist industry. No one would care if his wife, Anne Hathaway, had a cottage.

Without the First Folio there would be no dedicated Shakespeare theatre in Stratford, or at Shakespeare’s Globe on Bankside. There would be no Shakespeare festivals around the world, such as that in Stratford, Ontario. In fact, Stratford, Ontario, named in the 19th century for Shakespeare’s hometown, would now have a different name entirely, as would Stratfords in Ohio, Connecticut, Wisconsin, New Jersey and in New Zealand and Australia.

Halloween would be quite different without Macbeth, which popularised a trio of witches around a cauldron performing a spell. Valentine cliches of romantic love are unthinkable without the popularity of Romeo and Juliet. No sporting fixture between England and France would reach for the lines about Agincourt from Henry V.

A Shakespeare reduced in national prestige would not have been sufficiently prominent to be translated. Without German Shakespeare, we might never have had Freud’s version of the Oedipus complex, which he understood through his reading of Hamlet.

Karl Marx would not have conceptualised his theory of capital via Timon of Athens. And translations around the world – into more than 100 languages – would not have established Shakespeare as a global author.

There are other, more serious consequences of this fancy. Colonial rule in India would not have relied on Shakespearean study as the central text of empire. Othello’s murder of Desdemona might not have left its long shadow of prejudice about interracial marriage.

Perhaps the Confederate actor John Wilkes Booth would not have shot Abraham Lincoln at DC’s Ford’s Theatre, in April 1865 since he wouldn’t have been steeped in the role of the assassin Brutus in Julius Caesar.

The First Folio’s after-effects are far reaching indeed, touching fields of human psychology and geopolitics as well as literature, culture and theatre. No First Folio means no Shakespeare. And, whether you enjoy his works or not, that’s a hard reality to imagine.

Emma Smith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.