At the end of last week, Thomas Maddens, a filmmaker and activist based in Belgium, noticed something strange. A video about Palestine that he posted to TikTok with the word “genocide” suddenly stopped getting engagement on the platform after an initial spike.

“I thought I would have got millions of views,” Maddens told Al Jazeera, “but the engagement had stopped.”

Maddens is one of the hundreds of social media users who are accusing the world’s largest social media platforms – Facebook, Instagram, X, YouTube and TikTok – of censoring accounts or actively reducing the reach of pro-Palestine content, a practice known as shadowbanning.

Authors, activists, journalists, filmmakers and regular users around the world have said posts containing hashtags like “FreePalestine” and “IStandWithPalestine” as well as messages expressing support for civilian Palestinians killed by Israeli forces are being hidden by the platforms.

Some users have also accused Instagram, owned by Meta, of arbitrarily taking down posts that simply mention Palestine for violating “community guidelines”. Others said their Instagram Stories were hidden for sharing information about protests in support of Palestine in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. Some also reportedly complained about the word “terrorist” appearing near their Instagram biographies.

In a post on X on October 15, Meta spokesperson Andy Stone blamed the reduced reach of posts on a bug.

“This bug affected accounts equally around the globe and had nothing to do with the subject matter of the content – and we fixed it as quickly as possible,” Stone wrote.

When asked about the accusations of shadowbanning, Stone pointed Al Jazeera to a blog post that Meta published highlighting its latest efforts in tackling misinformation related to the Israel-Hamas war. The post said users who don’t agree with the company’s moderation decisions may appeal.

The BBC reported that Meta apologised for adding the word terrorist to pro-Palestinian accounts, saying the problem that “briefly caused inappropriate Arabic translations” has been fixed.

A TikTok spokesperson told Al Jazeera that the company “does not moderate or remove content based on political sensitivities”, adding that the platform removes “content that violates community guidelines, which apply equally to all content on TikTok”.

A YouTube spokesperson told Al Jazeera that the company’s systems prioritise connecting viewers with high-quality news and information from authoritative sources. The spokesperson also pointed Al Jazeera to pages outlining the company’s recommendation system, hate speech, harassment, and misinformation policies.

X did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests for comment.

Civil rights groups aren’t buying the platforms’ denials.

This month, 48 organisations, including 7amleh, the Arab Centre for Social Media Advancement, which advocates for digital rights of Palestinian and Arab civil society, issued a statement urging tech companies to respect Palestinian digital rights during the ongoing war.

“We are [concerned] about significant and disproportionate censorship of Palestinian voices through content takedowns and hiding hashtags, amongst other violations,” the statement said. “These restrictions on activists, civil society and human rights defenders represent a grave threat to freedom of expression and access to information, freedom of assembly, and political participation.”

Jalal Abukhater, 7amleh’s advocacy manager, told Al Jazeera that the organisation had documented 238 cases of pro-Palestinian censorship, mostly on Facebook and Instagram. These included content takedowns and account restrictions.

“There is a disproportionate effort that targets Palestine-related content,” Abukhater told Al Jazeera in an interview. “In contrast, the official Israeli narrative, as excessively violent as it could get, has got more of a free reign because Meta considers it to be coming from “official” entities, including from the Israeli military and government officials.”

‘Getting censored’

A 26-year-old marketing manager from Brussels who asked to remain anonymous to protect her identity, noticed that engagement she received on Instagram Stories dipped sharply when she posted about Palestine from her personal account. “I have around 800 followers, and I usually get 200 views for a story,” she told Al Jazeera. “But when I started posting about Palestine, I noticed my views getting lower.”

The woman said she was concerned because her story didn’t contain graphic images or include hate speech. “[They were] about understanding that Palestinian people are human and deserve to live freely in peace in the region,” she said. “Why is that getting censored?”

Another Instagram user, a 29-year-old mechanical engineer from India who also requested anonymity, noticed her Instagram Stories about protests in Los Angeles and California’s Bay Area had zero views even after an hour. “That was unusual,” she said. She then posted a selfie, which got the usual engagement she usually gets, she said.

Other users had similar experiences and took to the social media platforms themselves to complain. “After posting an Instagram story about the war in Gaza yesterday, my account was shadowbanned,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Azmat Khan posted on X. “Many colleagues and journalists [sic] friends have reported the same. It’s an extraordinary threat to the flow of information and credible journalism about an unprecedented war.”

Pakistani author Fatima Bhutto also said Instagram was shadowbanning her and limiting comments and story views. “I am learning so much about how democracies and big tech work together to suppress information during illegal wars they are unable to manufacture consent for,” she posted on X. In a video she posted to Instagram, she said her posts weren’t showing up in her followers’ feeds on the platform.

Khan and Bhutto did not respond to requests for comment from Al Jazeera.

Ameer Al-Khatahtbeg, the 25-year-old founder and editor-in-chief of Muslim, a news website that focuses on Muslim issues, noticed that posts from the publication reached significantly fewer people on Instagram over the past few days, plummeting from 1.2 million before the start of the war, to just over 160,000 a week into the war.

“The most major form of censorship that is being implemented is towards any account mentioning keywords such as ‘Palestine’, ‘Gaza’, ‘Hamas’, even ‘Al Quds’ & ‘Jerusalem’ in Instagram stories and posts alongside hashtags such as #FreePalestine, and #IStandWithPalestine,” Al-Khatahtbeg told Al Jazeera. “These posts aren’t reaching Instagram’s Explore page and are showing up on people’s main feed days later.”

Muslim wasn’t the only publication that accused social media platforms of censorship. Days after Hamas first attacked Israel, Mondoweiss, a pro-Palestine news outlet based in the United States, said TikTok banned its account and only restored it hours later after an online outcry. The Palestine-based Quds News Network posted on X that its Facebook page was suspended by Meta.

This isn’t the first time that social media platforms have been accused of censoring Palestinian voices.

An independent report commissioned by Meta after Israel’s war on Gaza in 2021 and made public a year later found that the company had negatively affected the human rights of Palestinian users in areas such as “freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, political participation, and non-discrimination”.

According to findings by 7amleh shared with Al Jazeera, Facebook received 913 appeals from Israel’s government to restrict or remove content on its platform from January to June 2020. Facebook consented to 81 percent of these requests.

“This isn’t new. Palestinians have faced censorship from Meta before and are experiencing it again,” Al-Khatahtbeg told Al Jazeera. A Meta spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

‘Tricking the algorithm’

Some people who said they experienced censorship on social media have been resorting to workarounds.

When posting to Instagram for instance, a Palestinian activist who did not want to be named for his safety told Al Jazeera that they “started breaking up” words. “When I wrote ‘Palestine’ or ‘ethnic cleansing’ or ‘apartheid’, I’d break the word with dots or slashes. I’d replace the letter ‘A’ with ‘@’. This is how I started tricking the algorithm.”

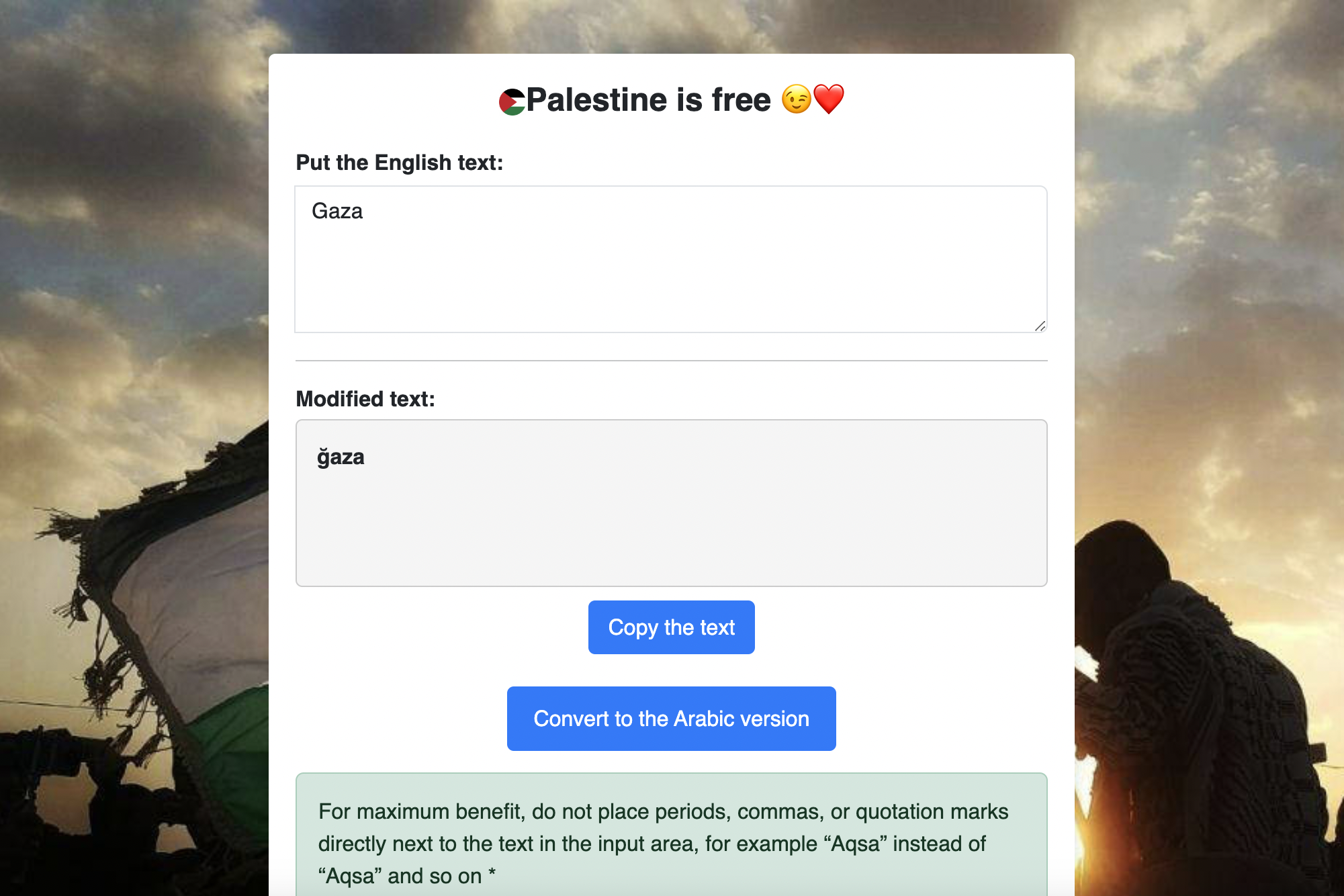

Mohammad Darwish, 31, the founder of a Bydotpy, a blockchain company based in Cairo, Egypt, created a website called “Free Palestine.bydotpy” that automates the same process. Typing “Gaza” into his website, for instance, automatically changes it to “ğaza”, which users can then copy and paste into the social media app of their choice.

“I don’t like anyone controlling me, and during tensions in Sheikh Jarrah, a Palestinian neighbourhood in East Jerusalem, I experienced a lot of restrictions,” Darwish told Al Jazeera, adding that Facebook also warned him about spreading “hate speech” back then.

“As a community of developers, we have a principle that ‘there is nothing that cannot be done with code.’ So I developed this tool, which has two versions, one for the Arabic language and the other for the English language,” he said.

“The function of the tool is to change the form of sentences to make it difficult for artificial intelligence and Facebook algorithms to understand the meaning of the text,” he added.

Shortly after noticing user complaints about social media censorship of pro-Palestine content, Florida-based law firm called Muslim Legal that focuses on helping American Muslims, set up a page on its website where anyone who had faced such censorship could share their experience. At the time of publishing, Muslim Legal had received more than 450 submissions.

“We noticed pages that were simply speaking out for justice for Palestinians were being simply shut down and banned without warning,” Hassan Shibly, the firm’s founder, told Al Jazeera in an interview. “We were also seeing people restricted for innocent comments.”

Shibly is now trying to take these complaints to the platforms to try to resolve them.

“The use of social media by the community is so essential,” he said. “It’s one of the ways we can push back against Islamophobic narratives. It’s one of the ways we can expose the war crimes that are happening. And it’s one of the tools we have to dismantle the propaganda and misinformation that is being used to justify the ethnic cleansing happening in Palestine by the Israelis.”

Need for transparency

In July, the European Union passed the Digital Services Act (DSA), seeking to tame Big Tech. Under this regulation, social media platforms are required to comply with rules that ensure digital security and also safeguard users’ freedom of expression.

“Platforms need to be very transparent and clear on what content is permitted under their terms and consistently and diligently enforce their own policies,” an EU spokesperson told Al Jazeera in a statement. “This is particularly relevant when it comes to violent and terrorist content.”

Crucially, the DSA also mandates transparency around shadowbanning and other kinds of content moderation.

“When an account gets restricted, the user must be informed,” the spokesperson said and added that users had the right to appeal the decision.

Some experts, however, expressed doubts on the effectiveness of the DSA in the current situation.

“In principle, the DSA covers shadowbanning,” Andrea Renda, senior research fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies, told Al Jazeera, “but in practice, it is going to be harder to prosecute this behaviour compared to the spread of misinformation on these platforms.”

Ultimately, censorship of Palestinian content hurts journalists, civil society and human rights defenders during a time of crisis, Abukhater said. “It especially prevents Palestinians from establishing context surrounding the events affecting their lives during this moment.

“It is crucial for companies to recognise their role at this vital moment and recognise that maintaining a steady flow of information to and from Palestine is absolutely essential to save lives and mitigate the human rights impact the censorship could have had.”