If you follow politics, sports, Hollywood or the arts, you’ve no doubt heard the insult “sellout” thrown around to describe someone perceived to have betrayed a core principle or shared value in their pursuit of personal gain.

The term has recently been hurled at a range of well-known targets: Donald Trump’s former chief of staff Mark Meadows for cooperating with a special counsel investigating election fraud in 2020; Kim Kardashian for advertising her personal brands as a form of women’s empowerment; even former NFL great Deion Sanders, for leaving Jackson State, a historically Black university, to coach at the University of Colorado.

Most people, I find, are familiar with this accusation. But few people really know the full story of “selling out” – when and where the term originated, how it spread across so many different sectors of American culture, and just why this insult hurts so much. These are the questions I set out to answer in the book I’m currently writing, tentatively titled “Sellouts! The Story of an American Insult.”

Through my research, I found that the idea of selling out originates with American politics — and more precisely, with the scandals of the Gilded Age.

Gilded Age origins

This era, which gets its name from Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner’s 1873 satirical novel “The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-day,” spans roughly from the 1870s to the 1900s. These decades saw the rise of industrial capitalism in the United States: people moving to cities, technologies transforming industries like the railroads, growing unrest and activism by workers, and crises erupting from an economy built around banks, stocks and corporations.

Until this time, the phrase “selling out” had largely been used to describe the sale of one’s stock or holdings – cattle, steel, grain, real estate. But by the 1870s, the term had quickly gained a new meaning as an insult for public figures — especially politicians — who had compromised their morals, and the needs of the community, in pursuit of illicit personal gain.

Of course, political scandals were hardly a novelty of the 1870s. What changed in the Gilded Age, historians suggest, was not the frequency or severity of unethical behavior by politicians, but rather the public’s awareness of the corruption plaguing the U.S. political system.

The Tweed Ring

Party politics has always involved graft: skimming off the top of budgets, directing contracts to favored firms, and securing offices for friends. But William Tweed, widely known as “Boss Tweed,” took this corruption to new heights.

In the 1860s, Tweed ran New York’s Democratic Party. His circle of influence extended to dozens of city and state offices. The Tweed Ring would provide someone with a job, and then the beneficiary would provide the ring with a kickback.

Whenever contracts were issued for services like carpentry, the ring inflated costs and skimmed off the extra — at first, adding a mere 10%, but later exaggerating these expenses wildly. One carpeting bill from a Tweed contractor ran to US$565,731, a cost high enough for a carpet in New York City to get “halfway to Albany.”

The ring would also buy up large chunks of city real estate, especially plots they knew were about to receive development projects. Estimates on the total wealth they siphoned through such graft range from $20 million to a staggering $200 million – or around $5 billion in 2024, when adjusted for inflation.

Tweed’s cronies also fixed elections with a boldness that’s unthinkable today; one drunken accomplice confessed he had voted at least 28 times on Election Day.

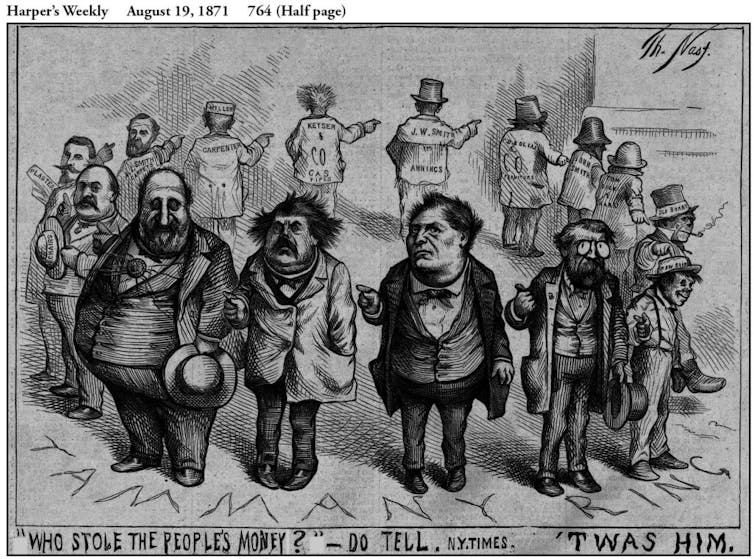

In 1870, The New York Times began an unprecedented journalistic exposé of Tweed and his ring. Their editorials used the phrase “selling out” to capture how city and state politics were manipulated by a corrupt few who lined their pockets and kept a chokehold on elections.

The Times also attacked other newspapers, like the New York World, which took large “advertising revenues” from Tweed, as evidence that these papers would “sell out to the highest bidder.” In a major coup, the Times eventually published complete records of the city’s finances, proving the ring’s corruption and landing Tweed inside the Ludlow Street Jail.

The Times’ crusade against Tweed pioneered a new, activist form of journalism, while also helping establish “selling out” as a recognizable idea in American life.

Later journalists, known as muckrakers, would launch their own famous investigations, such as Lincoln Steffens’ writing on political machines in other U.S. cities, David Graham Philips’ coverage of the widespread misdeeds of U.S. senators, and Ida Tarbell’s exposure of Standard Oil’s illicit business practices.

All used the newly popularized phrase “selling out” to describe the corruption of a democratic society. The “corrupt government of Illinois sold out its people to its own grafters,” wrote Steffens, whereas “the organized grafters of Missouri, Wisconsin, and Rhode Island sold, or are selling, out their States to bigger grafters outside.”

A contested concept

Over the next century, the idea of selling out spread from politics to numerous other corners of American culture: Novelists chastised peers who went to write for Hollywood as sellouts, while Black intellectuals debated what, if anything, Black elected officials had to do to be seen as “authentic” racial representatives and not sellouts.

For all its many uses in American culture, however, selling out remains a contested concept. For virtually any action that some people view as a betrayal, others will see as a rational choice.

Consider Bob Johnson, co-founder of Black Entertainment Television, who became the first Black billionaire when he sold the cable channel to Viacom in 2001. Some applauded his historic sale, but others accused Johnson of “selling out” this unique platform for Black voices.

Trump supporters may similarly see Meadows as a traitor — a sellout who abandoned his party’s leader to save his own skin. But Democrats may see him as a Republican who has chosen the values of the country over protecting his party’s standard-bearer. Each side follows its own logic.

Selling out, then, is not always a clear-cut transgression. When a group feels like one of its own has betrayed some shared values, there are often meaningful questions to be asked about what that group’s values ought to be in the first place.

Some critics have wondered whether selling out is an obsolete notion in an age when so many people aspire to be an influencer or entrepreneur. But as long as this term gets used to scold public figures like Meadows, it means Americans still believe some form of loyalty — to a community or a shared principle — matters more than personal gain.

But what does it say that so many Americans share the concern that success and integrity are in conflict, as if one comes at the expense of the other? Is it an increasingly unavoidable moral contradiction in a capitalist society?

“Selling out” evokes a widespread fear that anyone who pursues success will corrupt both their morality and their community. Some people – say, billionaires in their private jets – can perhaps suppress this fear more easily than others. But everyone knows its name.

Ian Afflerbach does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.