"Why do men want to own me?"

It was 1994 and I’d just turned 18. That May, Mum, my older sister and I moved from the family home in suburban Pakuranga to a modest town house in upscale Remuera. Dad had moved to Matheson Bay after the split but it was all very amicable. Although it’s possible I was too busy partying to notice.

The first thing my friends and I did was to jump in Virginia’s lemon-drop Datsun and time how long the drive was from Shore Road to High Street: 4.6kms and 10 minutes. Throughout the 90s, High Street was the coolest street in Auckland. It was the epicentre of creativity, where you’d find magazine and record label offices; record stores; and the new fashion stores we’d save our part-time job money to buy our clothes from: World, Karen Walker, Feline, Workshop and Cheryl Vullerman. The best clubs and cafes were there, too, or adjacent on Vulcan Lane: The Box, Cause Célèbre, Papa Jack’s, Voodoo Lounge, Escape, De Brett’s, Alfie’s, Rossini’s and Deschler’s. Everything we wanted or needed was on High Street.

1994 was my first year of an AIT Communications degree, and I soaked up everything life had to offer. Mostly nightclubs, bars and boys. No, that’s not fair. I was living this weird dichotomy where one version of me was a party girl and model, and the other was practicing piano, getting top marks, writing heartfelt poetry, and quoting Sylvia Plath and Hone Tūwhare in her diary. I was regularly tired and sick from partying, uni and working way too many hours—variously as a check-out girl at Newmarket Levene’s, salesperson at Early Settler in Ponsonby, door person at Café World nightclub in Parnell, and bar person at the Queen Street pool hall, Control Room (alongside legends Hans Hoeflich and Murray Hood). I thought I knew it all.

What I didn’t know, though, was how many near misses my friends and I had over those years. I say all the time now that we let things slide back then. But it wasn’t until recently reading my ragged old diaries — jammed with ticket stubs, photos, song lyrics, tiny handwriting and poems—that I realised just how close to the edge we often were.

We were molested by the bouncers at Rockgarden on our way into the club!

The exclamation mark says it all. I didn’t like being groped, but at the same time I understood that it was part of the power play. We were young and good looking, they knew we were underage, but they anointed us by allowing us and, in return, got to have a bit of a feel. Of course now, in a post #MeToo world, I understand this to be entirely unacceptable, and I would actually scratch out the eyes of any man who tried that on with my daughters.

In my 90s diaries, there are countless recollections of so-and-so feeling me up, or this guy grabbing my ass, or some guy pushing me against the wall and trying to kiss me. Also in its heyday, was the dark art of the male’s backhanded compliment.

At Piha with Jenny. I was sunbathing on the beach and some random guy came up to me and told me I’d be good looking if I put on weight.

Another guy said I’d be a spunk if my tits were bigger. One night at DTMs, when I was 16, some muscle-head guy grabbed my breast and so I slapped him. He slapped me back. It left a mark for days. No one did anything. That’s not the worst of it, but it’s what I can give you here today on the page.

My friends and I looked older than we were and started clubbing in Fifth Form (Year 10). God knows where my parents thought I was, but definitely not at Alfies, Site, The Coliseum, or DTMs. There were a lot of ‘sleepovers’ at Jenny’s place in New Lynn. Her parents were loose and I can distinctly feel the cold leather of her dad’s Kingswood bench seat under my bare hotpants-wearing legs when he picked us up from Alfies at 1am.

If a group of us were going out, we’d congregate at the house of whoever’s parents weren’t home or were most dupable, put on some tunes, down a bottle of Chardon, and decide who was wearing what. All items were common property. In the earlier Alfies days, we’d wear baggy 508 Levi’s with a grey-marle Elle Macpherson singlet. Later, there were hot pants and a black-with-white-stitching shirt, a pleated chiffon skirt, a David Pond crop-top with fringing. In my 1995–1996 Lenny Kravitz phase, there were the most amazing brick-coloured bell-bottoms from World, along with a denim duffer hat. A divine Zambesi fur vest and mini, bought second-hand from a friend. A belly-button piercing. A stretch blue lace tunic from Karen Walker. A silky wine-coloured Street Life slip-dress. There were denim jackets galore: red denim from Levi’s, khaki ones, and tailored ones with leather collars from Workshop. The boys we liked wore Feline overalls at DTM’s, or Workshop jeans and linen shirts.

Back then, and now, we couldn’t believe that no one thought it was weird and gross that the big mainstream clubs like Rockgarden and Steelz (the old Grapes) regularly held King of Studs or Bikini competitions, where punters would get up on stage and strip off to win bar tabs. Some clubs had free drinks for women or $2 drinks all night. We drank Illusion shakers, Vaults, vodka and Red Eye energy drink, 42s and grasshoppers. It was fairly standard not to pay for a single drink all night.

By Sixth Form we were going to Custom House and Escape, and I remember being completely blown away the first time I went down those dark stairs to The Box in December ’92. Grunge was just becoming a thing (and for that we went to Papa Jacks), but The Box introduced us to house music.

Drank Gimlet with Per, Si and Jen at Albert Park, and then went to the most incredible place, The Box. Danced all night. Met Sample Gee, the DJ from DTMs. We’re definitely going back next weekend!

That same year I went to SPQR for the first time and felt I had discovered a whole new planet, and I sure as hell wanted to be a native. It’s still my favourite place for a cocktail.

By the time I was in Seventh Form, my friends and I had frequented every place in town, with the favs being The Box, Cause Célèbre, Rossini’s, Rupin, Papa Jack’s, Eastside and Staircase. At the same time, I was head of music at St. Cuthbert’s and nailing an A Bursary in English, music, classics, bio and stats. I wanted to be a clinical psychologist or a musician or a writer. Or all of those things.

Why do men want to own me?

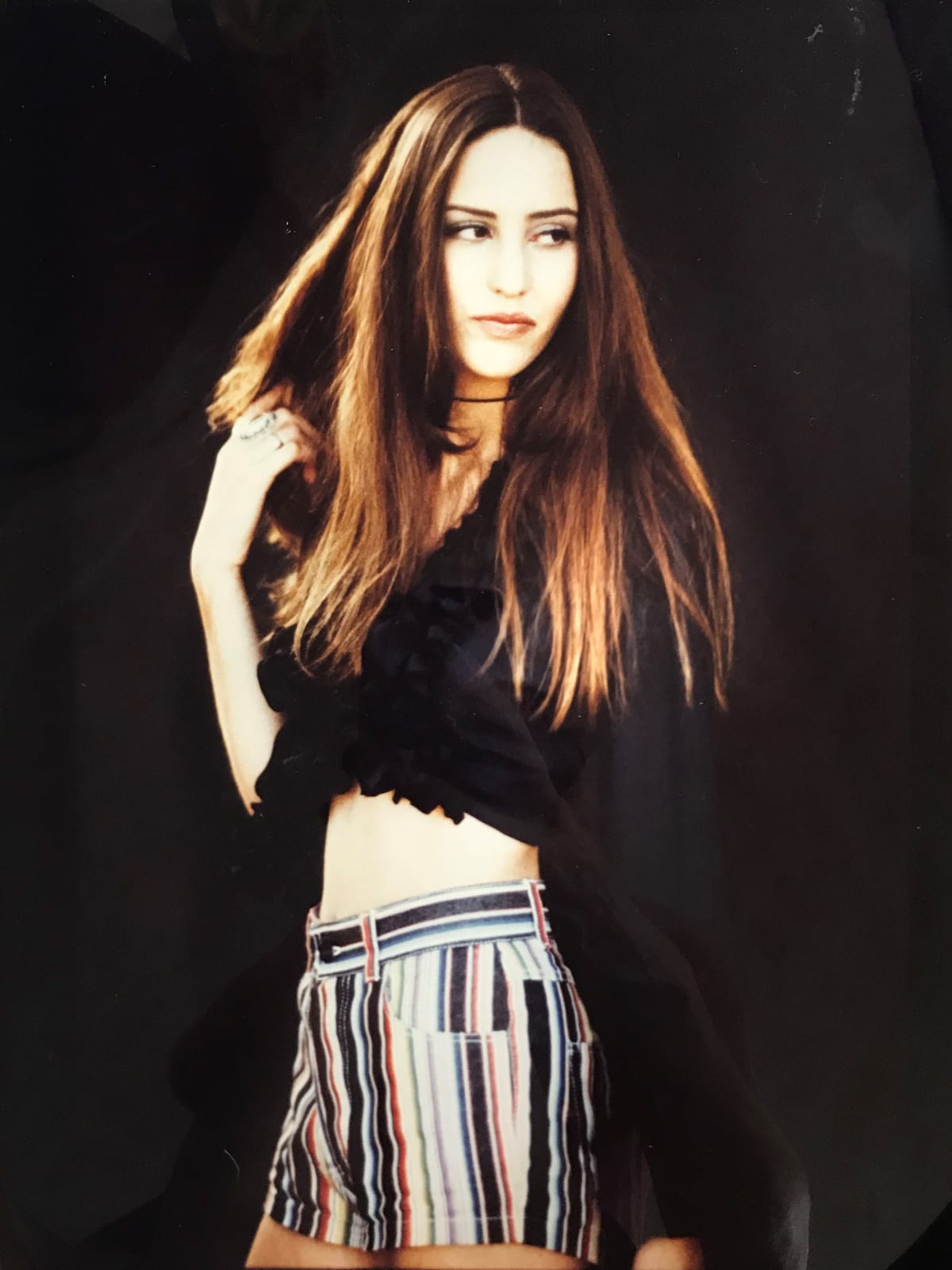

It was also in 1993 that modelling finally became a thing. Pavement magazine’s art director Glenn Hunt and his then-girlfriend (and now film director), Gwen Isaac, scouted me on Queen Street, asking if I’d been keen to shoot for fashion brand, Workshop. Um, yes! I had some Polaroids taken (by Daryl Ward, I think) and went to a casting for the first issue of Pavement. Melanie Bridge shot my original test photos. Soon after, I ended up on contract with top agency, Maysie Bestall-Cohen Model Management, and was a finalist in the Revlon Look of the Year Model Search at The Regent Hotel.

My first jobs were shoots for Doc Martens (alongside handsome Chris Sisarich, now a photographer) and an awful ‘grunge’ spread wearing red pleather in Woman’s Weekly. But mainly I walked the catwalk. I got to wear $10,000 gowns from Galleries Lafayette in Paris, be a bride more times than I can count, and wear all my favourite local labels. I made friends, had boyfriends, and went to parties. Being a model, and being in the High Street scene, gave me the ability to walk through just about any door. It might seem inconsequential now, but back then it was something. That street, those clubs, those people — they shaped who we became. Actually, to be granted entry to the coolest clubs is not dissimilar to being scouted to model. Both have power structures based on who they exclude.

Even with the safe guidance of a reputable modelling agency, I dodged a few bullets but ending up taking others.

Scouted by this guy, Derek King, from Starlets agency. He looked totally seedy.

It’s not until now that I've read about his secret life. He’s dead now, but he was a convicted paedophile with dozens of convictions involving girls as young as 12. He wanted me to go to his place on Constitution Hill so he could shoot a few Polaroids. Thank god for gut instincts.

Alarm bells didn’t ring in 1993, however, when Jeffrey Epstein’s buddy Jean-Luc Brunel told me at an agency casting that he wanted to catch up with me when he was back the following January. He was the influential French model scout who discovered Christy Turlington and Milla Jovovich. In 2021 he was charged with drugging and raping a 17-year-old girl in the 1990/2000s, and committed suicide in a jail cell in 2022. Luckily, that first casting was the last time I saw him.

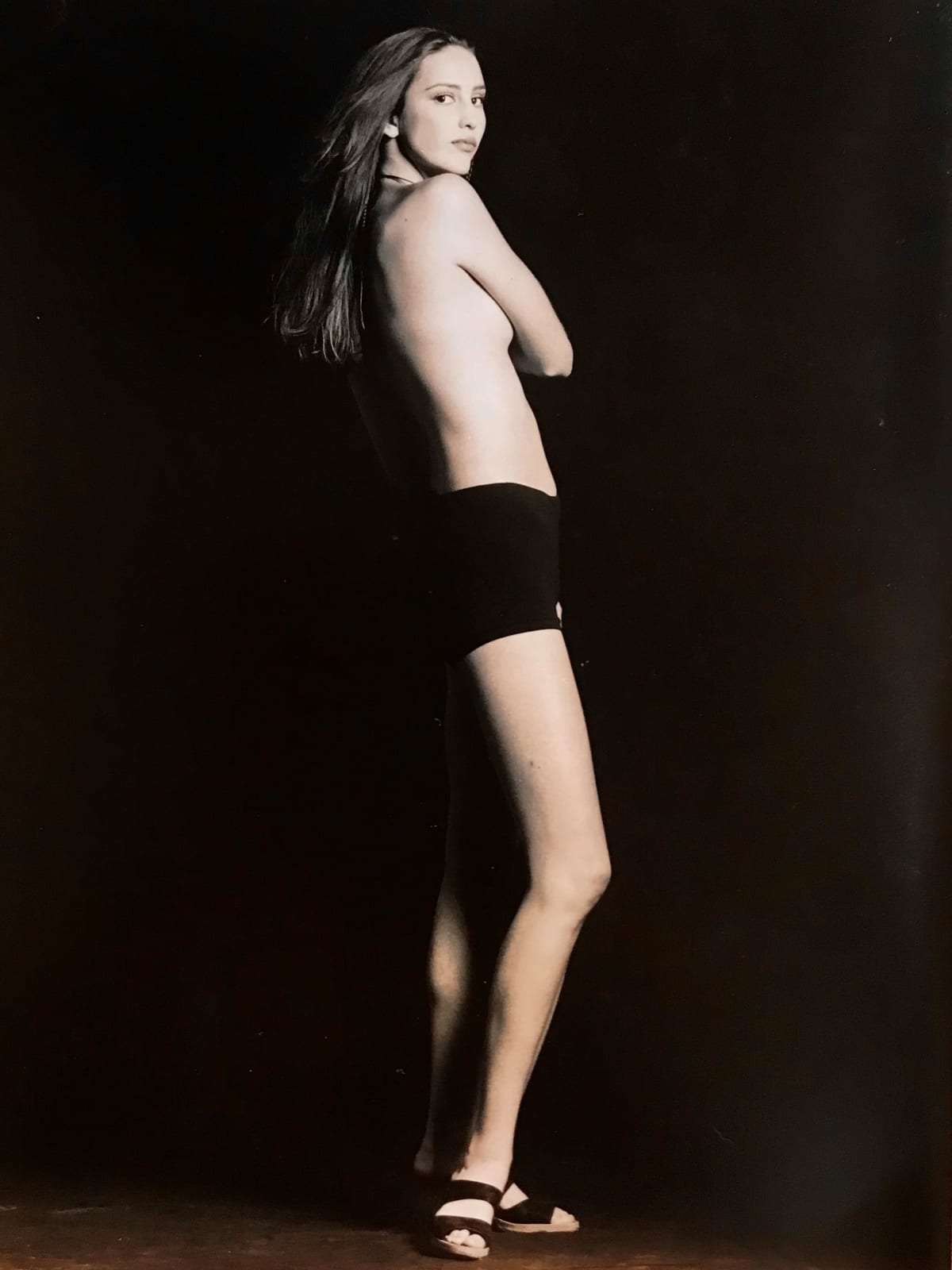

I wasn’t so lucky when I shot for a magazine’s ‘what’s hot’ pages. I was wearing these cool cow-print stockings and believed the photographer when he asked me to take off my top, that the image would be of my legs and the stockings. That my breasts would be blurred out. Imagine my shame and embarrassment at school the next month when the issue came out and my breasts were there for all to see. I was 17. I didn’t do anything about it. Because I didn’t know I could.

I can’t think how unfair and entirely human it is that the sense of our power and how to use it comes too late; that our understanding takes a while to catch up with what has occurred.

Perhaps because of my coming of age in the 90s, responsibility of care and illumination of power structures was something I took seriously throughout my tenure as owner of Nova Models and Talent—the subsequent name of Maysie Bestall-Cohen Model Management—from 1999 to 2009. The noughties was a decade of huge change. For one, Aotearoa’s senior roles were filled with women: Prime Minister Helen Clark, Governor-General Silvia Cartwright, Speaker Margaret Wilson, Chief Justice Sian Elias, and Telecom CEO Theresa Gattung. It was the decade of civil unions and the rise of the tabloid socialite. Hip hop dominated the charts and we wore low-cut everything. It was Juicy Couture, Harry Potter and Bratz dolls. It was the War on Afghanistan starting with the September 11 Attacks. I remember sitting at my desk at the agency that morning thinking it was entirely trivial and hollow to be phoning models to remind them to take their nude underwear and white heels to the bridal casting at Kevin Burkahn’s when the world was falling apart.

Social media stormed into our lives and changed everything. With the rise of celebrity influencers and Instagram scouting, the traditional model agency structure fractured. I sold at the right time, and others agencies either closed, or quickly pivoted to meet the new market. I’m not sure which is better, though: being judged on your looks in the 90s, or on how many followers you have in the 2010s and 2020s.

In my novel, Golden Days, the girl in cow-print stockings image becomes the centre point for an art piece that the 19-year-old protagonists, Becky and Zoe, create. The girl in the image wears a crown and there are fireworks behind her and, everywhere, are cut-out magazine images of men’s eyeballs. The poem Becky writes to go with the piece is this:

this is me:

a shape you think you know.

I was a model back then, yes. But I was also a thinker, composer, reader, writer, daughter, friend. There was so much more to me that wasn’t visible through the photographer’s lens. It may not be a lawsuit, but Golden Days was my way to lay that particular ghost to rest.

Golden Days by Caroline Barron (Affirm, $38) is available in bookstores nationwide. The author will appear with Megan Nicol Reid and Josie Shapiro in a panel about Female Friendship, at the Auckland Writers Festival on May 19. She wishes to thank Jarrod Haberfield and Melinda Williams for their assistance with this article