A memoir in 1701 words by a world champ, hungry wolf and Wellington poet

It’s a calm Tuesday night in Timaru. The skate park at Caroline Bay is quiet except for a teenage couple pashing in a Subaru WRX, the weird smell from the wharf that’s dominated Timaru Herald headlines throughout 2019 has subsided, and all through the town nothing stirs. Nothing except the big table at Little India, where the Curry Club - being my dad, Grant Peter Hamel, and his middle-aged friends finding a reason to get away from their families and indulge in some healthy male bonding - has its monthly meeting over tikka masala and litres of Kingfisher.

The Curry Club have a committee, minutes, rules and regulations, silly hats inspired by the Flintstones for some reason, a sponsored race and barbecue at the annual Timaru Harness Racing Club Day. And in addition to being known around town for the noticeable uniform and the parties down at the racetrack, the Curry Club is known for its generosity. Whenever someone’s kid has been picked to go to a youth athletics competition in Adelaide, to play age-grade netball for Canterbury, or to row for the NZ under-18 coxless four in Romania, you best believe the Curry Club is there to throw a little financial support behind the cause.

But this particular meeting – the one held on a calm Tuesday night in Timaru - is different. Despite playing rugby and cricket my entire childhood and adolescence, I was an incredibly mediocre athlete, a real battler, as enthusiastic as I was uncoordinated. My dad has known this for a long time and I’m sure he used this as leverage when he got up to give an impassioned speech about how the world poetry slam championships is as much a sporting event as any rugby match or track meet and that his son (me: New Zealand Poetry Slam champ Jordan Hamel) is just as deserving of that famed Curry Club generosity, a speech so impassioned and considered, it thawed the heart of even the most rugged traditionalist amongst them.

At least that’s how I imagine it went anyway.

*

I felt disgusted by the urge I felt as a teenager to write poetry. It wasn’t the masculinity I had grown up around in Timaru. It wasn’t Richie McCaw or Chris Cairns, or even My House My Castle’s Cocksy. Poetry was the stuff that got Kyle kicked out of Year 10 English after he asked Mrs. Cantwell why the war poets spent their time writing "gay-ass songs instead of killing people?" Nah. In my head there was no reasonable path to acceptance there. I kept it quiet, didn’t tell anyone. Slurs and interrogations were thrown around in school common rooms and barn parties enough as it was, I didn’t need to invite any more of that.

I left Timaru for Otago University, trading cold Saturdays on makeshift farm paddock rugby fields for beer bongs and burning couches. I gained new friends and new kilograms, I discovered dubstep and party pills, I learnt how fun it was to dip your toes in any vice or whim imaginable outside the supervision and constraints of my old community. Any except one.

Despite my new lease on life and all the distractions, the writing didn’t stop. I read every dusty old collection of poetry I could find in the uni library or second-hand bookstore. I snuck away to David Eggleton readings in the English department or at a half-empty pub and wished I wasn’t too scared to say hi after. I slowly started replacing my pillars of masculinity with Baxter and Bukowski and other cancelled writers.

I was still terrified people would find out about my secret life. I wrote terrible poems under the world's worst pseudonym, Tim. A. Roux, published in Otago’s finest and only student publication, Critic. Poems with appalling names like "Our lady of virtue", "Afternoons of suspended possibility" and "City of literature… and gentrification" (Jesus Christ, Jordan). Poems that I have since worked hard to scrub from existence.

I moved to Wellington and things felt a little different. I told some university friends about my double life as a poet and they were supportive, saying things like "that’s cool man", "I had no idea you were a writer, awesome" and "I’ve never got poetry eh, what’s the deal with it?" I even got up the courage to do a drunken impromptu reading of a Tim A. Roux special while dressed as Colin Craig during a 2014 general election-themed flat party. I was finally becoming myself. Just like Colin Craig during the 2014 general election, I was learning to trust the people in my life, learning to take risks and say yes.

The first time I ever did a proper reading, it was at a music festival in a forest with Hera Lindsay Bird. I threw up from the nerves beforehand. Vomit aside, it went really well. People seemed to enjoy it, even if they were surprised it was me up there. I was definitely surprised it was me up there. It felt like the start of something different.

The fear was still there of course, it always will be. But now it had to contend with a growing urge to be seen and heard, to chase the first post-reading rush like the Wile E. Coyote of NZ poetry. So, like any out of town, non-IIML, wayward poet, I stumbled into the spoken word scene. Met with open arms and open mics, I found a place that was as supportive as it was chaotic. A place that didn’t do middles, just highs and lows, moments of pure exhilaration scattered between poets and poems, both electrifying and atrocious.

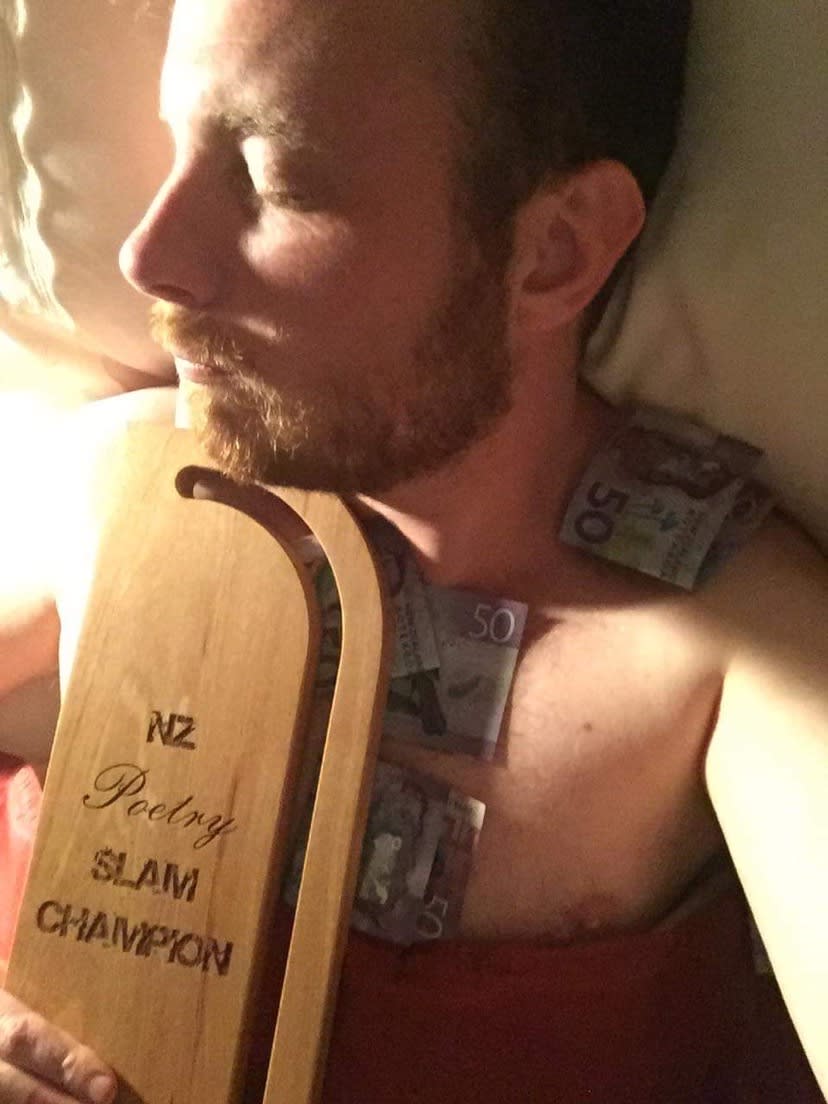

Not only did it give me a space to experiment, it gave me something I never thought I’d have, a national title. In the summer of late-2018, 10 months after that reading in the forest, I became the New Zealand poetry slam champion. I got a large wooden trophy I could sleep with, enough cash to fill up two tanks of 2018-priced petrol, and the chance to fly all the way to the US to compete against the best of the world. I was an international athlete! Just like Richie McCaw or Barbara Kendall.

*

Inside every writer there are two wolves and they’re both awful. One of them hungers for attention and validation, chasing any scent it picks up that might lead to it. The other is out of sight, reading, hiding. Writing and spoken word have given me the smallest amount of notoriety with a hard ceiling. It’s a level I am uncomfortable with for being too much and too little at the same time. I let these two wolves fight over the meat of the day, then it starts all over again.

I think we’re all hardwired to seek affirmation in some form. Occasionally writers tell me they write strictly for themselves and they’d be content if no one else ever wrote or responded to their work. I nod along politely while the diva wolf is in my ear whispering "this person is either a liar or a sociopath, there’s no validation outside of the external, strike them down now and steal their followers." While wolf number two is asleep dreaming of a secluded cabin on Stewart Island.

I’ve seen people turn themselves inside out for attention, slams, prizes, publication, anything, everything. At the end of the day, considering the finite space and attention that exists for what we do, combined with Twitter and Instagram, our primary means of communicating our work and have any sort of discourse, being specifically engineered to amplify our worst impulses and insecurities, it’s easy to see how it can chew up a person so fast.

Maybe I need a couple of years in the Siberian wilderness away from the internet. Maybe I need to savour being known amongst a tiny community of Twitter-addicted literary types and sycophants. A well-dressed man with two villas in Karori asked my friend and I recently at a fancy arts event we stumbled into whether we made a living off our poetry. We laughed so hard we nearly choked on the complimentary arancini balls.

Writing my debut collection of poems Everyone is Everyone Except You has felt like the right vehicle for coming to terms with all this mess, the desire, the fear, all the other gross fluid that comes out in the process. It hasn’t led to any life-changing revelations, but I think it does document the insecurities and all the contradictions that hang around inside me. A collection of feelings and experiences that are both entirely real and completely made up at the same time. An attempt to use poetry to reject masculinity and reclaim it. A record of my constant pining for attention and invisibility. A trip to a party and feeling like the best and worst person in the room, the hero and the villain, and realising you’re probably neither. A reflection of how it feels to be sometimes deeply depressed and sometimes incredibly excited about living.

The last time I cried during a reading was because there are things in my poems I’ve never said out loud before and that's no one’s fault but mine. Because no one ever cares about things as much as you think they do. People in your life are just generally happy that you’re happy, then they go back to worrying about their own stuff. Turns out I never actually had to hide who I really was from anyone, but I did it anyway.

A wise poet and spoken word legend once told me after a reading, "I fuckin hate my first collection, I should’ve waited. Don’t be like me, wait." So I did. I turned my manuscript inside out, upside down, back to front, time and time again, until the book I wanted to write finally emerged.

I know it’s an extremely un-New Zealand thing to say, but I think my book is quite good. It needs to be, or that weird little kid sitting in the back of Mrs Cantwell’s English class holding an old copy of a Hone Tuwhare collection, dreaming of writing his own one day, would never forgive me. He’s come this far after all.

Everyone is Everyone Except You by Jordan Hamel (Dead Bird Books, $30) is being launched in Wellington at Unity Books tomorrow night, May 18, and in Auckland at the Soap Dancehall in Beresford St on Thursday night, May 19. The book is available in bookstores nationwide, including the author's home city of Timaru.

Tomorrow in ReadingRoom: a killing in Inglewood, as remembered in a new memoir by ex-journo Jim Tucker.