In their frantic effort to declare “nothing to see here”, Australia’s intelligence chiefs are drawing more attention to the Solomons-China pact that’s continuing to cause Scott Morrison enormous grief.

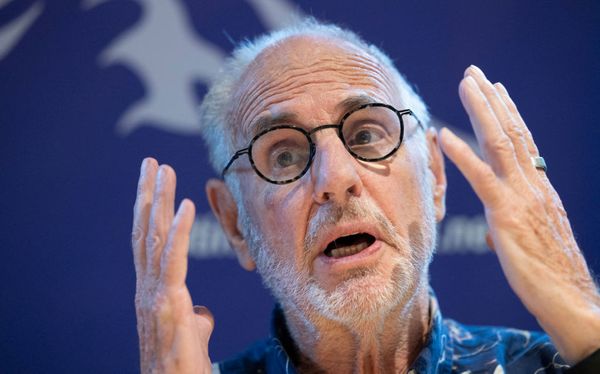

Today’s instalment is from Andrew Shearer, the long-time Coalition adviser elevated to director-general of the Office of National Intelligence in 2020. Australia’s failure to be aware of the pact, he said this morning, “wasn’t an intelligence failure, this strategy has been unfolding for a number of years. I think for those of us watching closely there were signs of this well over a decade ago, and we’ve seen this building presence…”

“Signs” are what the rest of us can read. Our intelligence agencies, especially ASIS, aren’t paid and given extensive powers to tell us what’s in the Solomon Star; they’re not employed to give us a sense of the vibe, but to provide intelligence on a regular basis. It’s hard to imagine a definition of “intelligence failure” that does not include failing to know about an important negotiation between a major power and a small neighbour.

But to take Shearer at his word, what does it mean that intelligence services were aware of “signs” of a “strategy [that] has been unfolding for a number of years”? It means — a conclusion would prefer not to be drawn — that the government was fully cognisant of what China was attempting to do but complacent, or incompetent, about preventing it.

What advice did intelligence services, for example, give about the impact on regional sentiment of Australia’s climate inaction? Or the self-interested nature of so much of Australia’s aid, or its neo-colonialist behaviour toward regional governments? Did they also drink the Kool-Aid about how much we’re loved by “our Pacific family”? Or were these issues left to the diplomats of an increasingly sidelined Department of Foreign Affairs, under the low-impact, low-energy Marise Payne?

Shearer’s comments merely make the case stronger for declassifying the intelligence — as Crikey has previously urged — in relation to the Solomons-China pact, or conducting an inquiry into the failure.

Such an inquiry also needs to address the aftermath of failure, as intelligence agency heads moved to evade responsibility for it — in particular, anonymous claims made to press gallery stenographers that the leak of the agreement draft on March 24 was the work of Australian intelligence agencies.

If the claim is correct — or even suspected to be correct — it has placed under suspicion anyone connected to the leaking of the draft, which was first posted online by an adviser to the Malaita province Premier Daniel Suidani. In effect, Australian intelligence sources are giving both the Solomons and the Chinese governments pointers as to who is connected to Australian agencies like ASIS in the region. A check of phone logs and email traffic might readily verify the identity of someone who has been acting as a source for ASIS anonymously until now.

Arguably, it was reckless of journalists to publish the claims, and certainly reckless for intelligence officials — who are supposed to understand the value of protecting assets — to make them. That they were made to deflect blame from agencies makes it all the worse.

It might also suggest that if agencies like ASIS had trouble knowing what was happening before, they’ll have an even more difficult time if sources suspect they may be outed to soothe the egos of intelligence chiefs in Canberra.