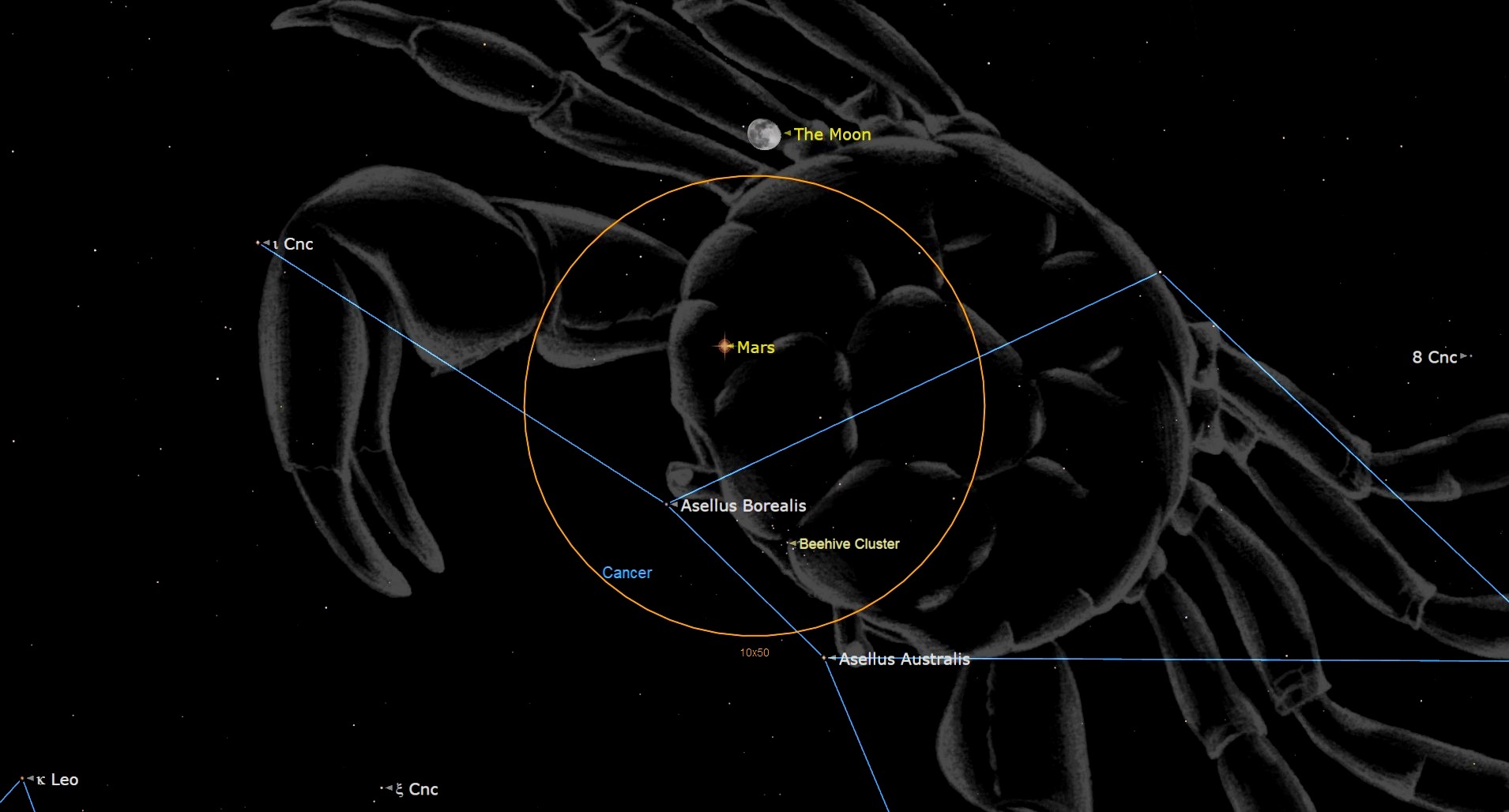

If the weather is clear where you live on Tuesday evening (Dec. 17), look low above the east-northeast horizon at around 8:00 p.m. local standard time and you'll see the waning gibbous moon, 89% illuminated, accompanied by a very bright and colorful star directly below it and two bright stars will above it.

The two stars hovering well above the moon mark the heads of Gemini, the Twins. Pollux will be closest to the moon, while the somewhat dimmer star Castor will lie just above it.

Meanwhile, glowing below the moon like an orange luminary in the dark of the night is not a star, but one of our planetary neighbors: Mars. Its relatively close proximity to the moon will no doubt have not a few night owls asking the question, "Just what is that fiery-colored thing that’s glowing below the moon?" Sometimes, such occasions bring with them a sudden rash of phone calls to local planetariums, weather offices, TV and radio stations and even police precincts.

Want to see Mars or the features of the moon up close? The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of celestial objects. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review.

Mars currently comes up like a brand of fire in the east-northeast nearly three hours after sunset; it’s now rising about 5.5 minutes earlier each night. This golden-orange world has now flamed up to magnitude -0.9.

Right now, after it makes its first appearance above the horizon, Mars has now risen to the rank of the fifth brightest object in the pre-midnight evening sky, rivaled only by the moon, Venus, Jupiter and the brightest of all stars, Sirius. In contrast, Pollux, the brighter of the "Twin Stars," shines only 1/7th as bright.

Good telescopic views of Mars become possible about 10:30 p.m., as soon as the planet has climbed well up out of the murky, shaky skies near the horizon.

Not a particularly favorable close approach

Next month, on Jan. 15, Mars will be at opposition to the sun, when it will be in the sky all night; rising at sunset, reaching its highest point in the south in the middle of the night and setting at sunrise. Oppositions of Mars occur on an average of about every 2.2 years. But not all Martian oppositions are alike.

Those who witnessed its spectacular approach to within 35.78 million miles (57.58 million km) of Earth in 2018 then had to settle for increasingly poorer views of the red planet as the Earth-Mars orbital geometry became more unfavorable. In contrast to 2018, Mars came no closer to Earth than 50.6 million miles (81.4 million km) in 2022, and next month it will get no closer than 59.7 million miles (96.0 million km) to Earth.

And during the opposition occurring in February 2027, Mars will be even farther away: 63.0 million miles (101.4 million km). In fact, we will have to wait until May 2031 for an opposition where Mars will come closer to Earth compared to next month.

Nonetheless, over the next eight weeks Mars will be at its very best for this particular apparition. Mars is currently proving to be a most thrilling – though also a most challenging – planetary target at this time. Through a six-inch telescope, magnifying at 150-power, the planet’s gibbous disk, 96-percent illuminated and measuring 13 arc seconds in diameter, will appear in the eyepiece to be as large as the moon would look to the unaided eye.

But because it will continue to slowly approach the Earth during the next 26 days – getting closer to us by about 234,600 miles (377,500 km) each day – the planet’s apparent size will continue to slowly grow through the planet’s closest encounter to us during the second week in January.

Don’t miss this near miss!

For those of us in North America, early Wednesday morning will also mean a very close conjunction of the moon to Mars (also sometimes called an "appulse"). The moon, moving around the Earth in an easterly direction at roughly its own diameter each hour will seem to creep slowly toward, and ultimately pass just above the ochre planet.

When the moon and Mars first become visible Tuesday evening, they will be separated by about two or three degrees. When they will appear closest, Mars will appear to glide only fractions of a degree below the moon’s lower limb. On the West Coast, closest approach will come soon after midnight Pacific Time high in the east-southeast sky, while for the East Coast, least separation between Mars and the moon will come at around 5 a.m. Eastern Time with both moon and planet well up in the west-northwest.

"Mars eclipse"

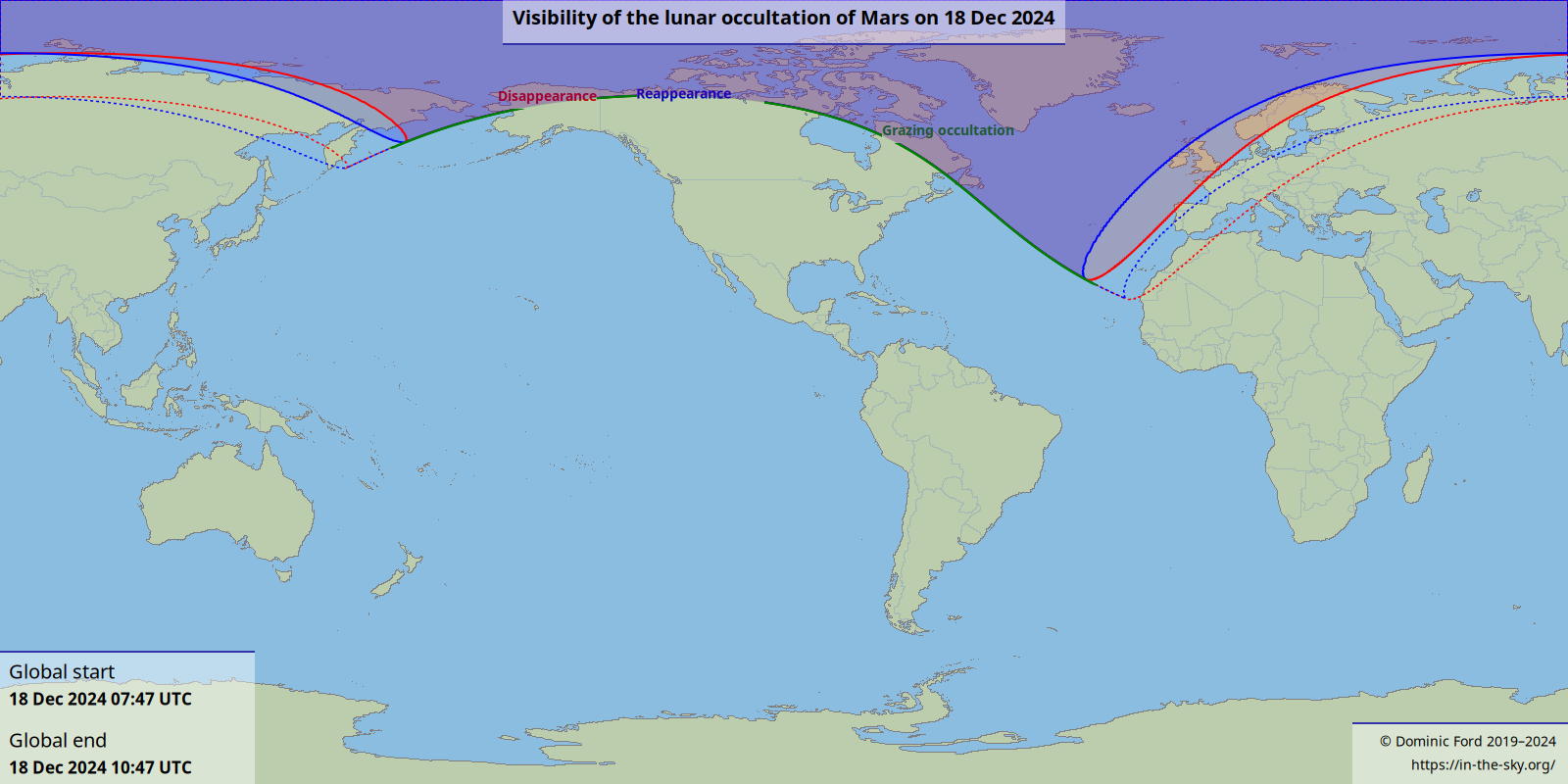

As a bonus, for those inhabitants of northern Alaska as well as the far-northern regions of Canada, including parts of Labrador and Newfoundland, the moon will appear – for a short time – to hide or eclipse Mars from view during the predawn hours on Wednesday morning. The actual term is called an occultation (from the Latin ocultare, meaning "to hide"). An opportunity to see the moon occult a bright planet at night does not happen too often, so for those who are fortunate to live in the occultation zone, this upcoming event is one that really should not be missed.

Timings for many locations, as well as a map of the visibility zone of this “Mars eclipse,” courtesy of David Dunham of the International Occultation Timers Association (IOTA) can be found at the group's website.

Even though the rest of North America will miss out on the occultation, Mars will almost command people to gawk at it, as it slowly appears to glide above the moon during Tuesday night into Wednesday morning.

And the moon, of course, is nowhere near Mars in space. On this night the moon will be 235,300 miles (378,600 km) away; that's still about 280 times closer than Mars.

But on this special night, they will be aligned in such a way to be positioned right next to each other, making for a head-turning sight!

If you want to try taking your own photos of the close approach of the moon and Saturn, check out our guides on how to photograph the moon and how to photograph the planets. And if you don't have everything you need for shooting the night sky, check out our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.