The seditious conspiracy convictions of Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes and another leader in the far-right extremist group show that jurors are willing to hold accountable not just the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, but those who schemed to subvert the 2020 election.

Tuesday's verdict, while not a total win for the Justice Department, gives momentum to investigators just as the newly named special counsel ramps up his probe into key aspects of the insurrection fueled by President Donald Trump’s lies of a stolen election.

As Democrats call for charges to be brought against Trump and the House committee investigating the insurrection weighs making a criminal referral to the Justice Department, the Oath Keepers verdict may embolden investigators to build cases against other major players behind the push to keep Trump in power.

“The fact that they got two convictions for seditious conspiracy gives DOJ the confidence that they can pursue other higher-ups and charge seditious conspiracy as well because certainly a D.C. jury accepted it," said Jeffrey Jacobovitz, a Washington white-collar criminal defense attorney. "If I’m one of the other leaders of the insurrection, I would be very concerned about what kind of charges they could bring.”

They are the first seditious conspiracy convictions at trial in decades and are significant because the legally complex charge can be difficult for juries to grasp and for prosecutors to prove, especially in an ultimately unsuccessful plot. The sprawling Capitol riot probe has already led to the arrest of more than 900 people across the U.S. and could result in hundreds of more charges, but Rhodes and his associates were the first to stand trial on the Civil War-era offense.

Jurors found Rhodes and Kelly Meggs, who led the Florida chapter of the antigovernment group, guilty of sedition for plotting to use force to block the presidential transfer from Trump to Joe Biden. Three other co-defendants were acquitted of the charge, but all five were convicted of obstructing Congress' certification of the electoral vote, which — like seditious conspiracy — carries up to 20 years in prison.

The verdict, while split, could strengthen the Justice Department's hand as it gears up to try a second group of Oath Keepers as well as former Proud Boys national chairman Enrique Tarrio and other top leaders for seditious conspiracy. With both trials slated to begin next month, the convictions could spur new plea deals.

“If I am a defense attorney for any of those defendants, today I am reaching out to my client to say: ‘We need to have a conversation about whether you still want to go to trial,’" said Barbara McQuade, who served as U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan.

Rhodes never went into the Capitol, but prosecutors spent weeks methodically making the case that he rallied his followers, amassed weapons and prepared armed teams outside Washington with the singular goal of stopping Biden from becoming president. In hundreds of messages shown to jurors, Rhodes urged his follow extremists to fight to defend Trump and warned of a civil war if Biden became president. On Jan. 6, Oath Keepers dressed in battle gear joined the angry mob of Trump supporters and pushed into the Capitol.

“Individuals that weren’t at the scene but were involved in the planning and plotting of this attack on the U.S. Capitol — they should be very nervous right now,” said Jimmy Gurule, a former federal prosecutor who's now a professor at the University of Norte Dame Law School.

Testimony showed how the Oath Keepers were inspired and energized by Trump and his false claims of election fraud. After Trump tweeted Dec. 19, 2020, about a “big protest” at the upcoming joint session of Congress on Jan. 6 that he promised would "be wild,” Meggs wrote in a message: “He wants us to make it WILD that’s what he’s saying. He called us all to the Capitol and wants us to make it wild!!!”

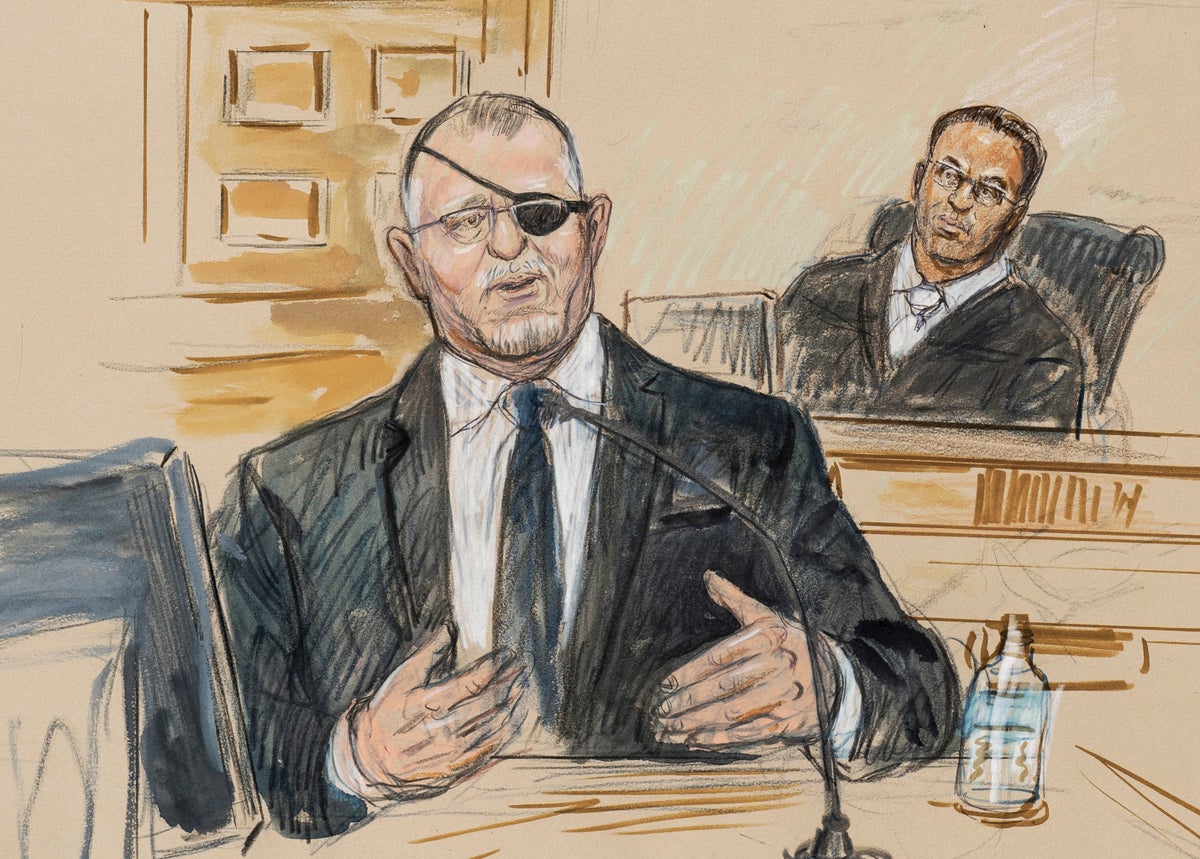

In a risky move, Rhodes took the witness stand and tried to cast his violent rhetoric as bombastic talk, separate from the storming of the Capitol itself. But the public speaking skills that helped him build one of the largest antigovernment organizations in U.S. history didn't persuade jurors — even though two co-defendants who also took the stand were cleared of the seditious conspiracy charge.

Ultimately, it appeared that Rhodes' testimony was outweighed by the vast volume of his own writings, text messages and a recorded conversation.

“The question is going to be whether or not there is similar communication, similar statements, similar admissions by other individuals higher up in the Trump administration,” Gurule said.

Charges stemming from the insurrection thus far have focused largely on those who stormed the Capitol, attacked police officers, smashed windows and sent lawmakers running for their lives. But Justice Department officials have already shown acute interest in speaking with members of the Trump administration about efforts to undo the election.

The Associated Press and other news organizations have reported, for instance, that Trump’s White House counsel, Pat Cipollone, and his top deputy, Patrick Philbin, appeared last summer before a federal grand jury after receiving subpoenas. Marc Short, a top aide to Vice President Mike Pence, also has testified.

The Justice Department also has issued a wave of subpoenas related to a scheme to elevate alternate, or fake, electors in battleground states who would invalidate Biden’s win. It has scrutinized the fundraising practices of Trump’s political action committee, with subpoenas seeking records of communications with Trump-allied lawyers who supported efforts to overturn the election results.

As for Trump himself, legal experts have expressed conflicting views about his direct exposure to prosecution relating to the events of Jan. 6 and the efforts to undo the election, with some suggesting that the most vulnerability he has would relate to any attempt to defraud the American public by preventing the lawful transfer of presidential power.

George Washington University law professor Stephen Saltzburg, a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s criminal division, said he believes the jury’s verdict will have “zero impact” on the investigation of Trump.

“What the jury did doesn’t change any of the facts surrounding former President Trump,” he said. “The fact that these guys were convicted doesn’t make proving a case against Trump any easier.”

Oversight of key aspects of the Jan. 6 investigation and the investigation into classified records kept at Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate fall now to special counsel Jack Smith. He returned to the Justice Department in 2010 to lead its vaunted public integrity section after the botched prosecution of a Republican senator and is described by colleagues as a hard-charging, aggressive and energetic prosecutor with a track record of bringing cases without regard to political considerations.

_____

Richer reported from Boston. Associated Press reporter Eric Tucker contributed from Washington.