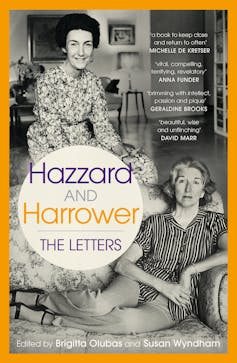

The publication of the letters between Australian writers Shirley Hazzard (1931-2016) and Elizabeth Harrower (1928-2020), edited by literary scholar Brigitta Olubas and journalist Susan Wyndham, provides a picture of mid-century life from the perspectives of two exemplary and, for too long in this country, underappreciated novelists.

Review: Hazzard and Harrower: The Letters – edited by Brigitta Olubas and Susan Wyndham (NewSouth)

The letters outline the women’s four-decade friendship. Written from various locations (Sydney, London, New York, Rome, Capri) between 1966 and 2008, they describe the contours of their lives, their writing habits, their reading discoveries and preferences.

These are seen through the prism of their liberal progressive views on domestic and world politics. Among other events, their correspondence touches on the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, the election of the Whitlam government and its dismissal, the Arab-Israeli War, civil unrest in the United States, green bans in Sydney, and the opening of the Opera House.

As writers, Hazzard and Harrower had one eye on the likelihood of their letters becoming public. They each deposited the carefully composed, often typed letters with their papers in the archive.

What does this presume for the writers and readers of such letters? Both women remark that they are writing hurriedly to catch the post, but awareness of their missives’ future slips into view – through topics raised, expanded upon or avoided, and the public figures who are named or not. Discretion and intimacy are in tonal counterpoint throughout.

Writers in exile

Three years apart in age, Hazzard and Harrower were both formed as writers by the fact of being Australian-born women. Neither identified as feminist, though each contributed to a woman-oriented aesthetic in their devotion to the novel form. Hazzard paid close attention to the wider forces obstructing the nearer force of love’s desire; Harrower described women constrained by oppressive domestic and familial relations.

The letters are grouped into three periods with a brief editors’ overview. There are regular edits within the selected letters, which have been drawn from a much larger corpus, making the collection into a fluent text for a general reader.

Olubas is Hazzard’s official biographer, having edited the first critical edition of Hazzard scholarship in 2014; Wyndham, as a literary editor, had interviewed both writers and visited Hazzard at her homes in Capri and New York. Their introduction provides some clues as to why their subjects exiled themselves, either permanently or temporarily, from Australia.

Hazzard left permanently at the age of 16. Her father’s role as Trade Commissioner took the family to various countries after 1945. She spent time in Hong Kong and New Zealand, before arriving in New York. There, at the age of 20, she began work as a secretary at the United Nations, which also enabled her to work for the UN in Naples.

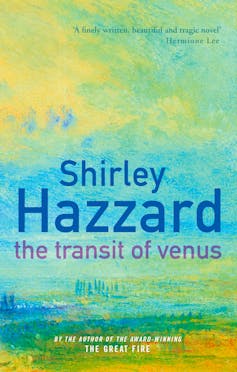

Within a decade, Hazzard was able to focus on writing full time. She went on to publish four novels: The Evening of the Holiday (1966), The Bay of Noon (1970), The Transit of Venus (1980), and the Miles Franklin and National Book Award winning The Great Fire (2004). There were solo and co-authored nonfiction titles between the fiction.

Financial security coincided with Hazzard’s cold-call submission to the New Yorker magazine, which contracted her for more short fiction. Within a few short years, an even grander level of financial security arrived with her marriage to the wealthy writer and translator, Francis Steegmuller. The couple, introduced to each other by Muriel Spark, became known as “the Steegs”.

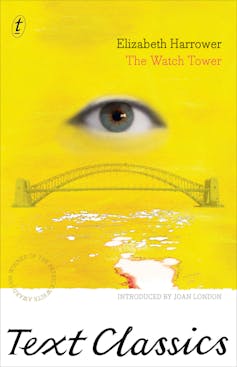

Harrower lived in London for eight years in the 1950s where she wrote and published three of her four novels: Down in the City (1957), The Long Prospect (1958) and The Catherine Wheel (1960). Her acclaimed fourth novel The Watch Tower (1966) was written after her return to Australia.

In 1971, Harrower withdrew the manuscript of her fifth novel from publication, seemingly as a consequence of a negative reader’s report. It did not see the light of day for 50 years. Text Publishing eventually released the long-buried In Certain Circles in 2014. The novel was shortlisted for the Stella Prize the following year. Short fiction written and published decades earlier was also reissued by Text under the title A Few Days in the Country and Other Stories (2015).

Now into her ninth decade, the “revival” of Harrower’s oeuvre had begun, not only in Australia, but in the United Kingdom and United States. Facilitated by Michael Heyward at Text Publishing, this revival coincided with Hazzard’s revival through Olubas’s scholarship.

Social work

Hazzard and Harrower also exiled themselves from their families in different ways.

Hazzard’s estrangement was practically complete with her parents’ divorce in the early 1950s. Her mother’s volatile mental health could sometimes result in horrifying episodes. “I just want to say that I hate you and your sister,” she wrote in one letter to her daughter.

Harrower grew up in Newcastle, a town she found ugly and constraining like her mother’s second marriage, which also ended in divorce. In an interview conducted late in life, Harrower said: “having spent very little time with my few relatives, I don’t remember them very well or often”.

The women wrote to each other for six years before they met in London in 1972. Across 40 years, they met only six times. The letter writing began just as Harrower had given up fiction writing altogether. She had published three novels by the time of Hazzard’s first, but their writing lives had clearly diverged by the start of their correspondence.

Their celebration of newly arrived books was all one-sided. Harrower congratulates the Steegs’ on their new works, but they were unable to reciprocate. Both Steegmullers expressed great admiration for The Long Prospect and The Watch Tower, but, poignantly, during their decades of correspondence, Hazzard’s occasional prompting – “do let us have a prospect of a (new) Harrower to read” – was not rewarded with new work.

Hazzard remarks to Harrower on the similarity of their Australian childhoods in setting up their writing lives, but the material conditions enabling that writing could not have been more different. The Steegs, with an art collection worthy of loan to the Metropolitan Museum, established their writing discipline as if it too were a fine art. In one letter, we learn of them sitting at their breakfast table, looking across at each other, while making annotations on their different editions of Gibbons’ History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

While far from impoverished, Harrower appears to be seeking both the time and peace of mind to write. She was tirelessly involved with the business of supporting writers and writing events, including securing Hazzard’s entrée to literary events, high-profile appointments and private dinner parties back in Australia. Harrower’s close friend and neighbour, Patrick White, was a great supporter of her writing, but chided her for living as if she were a “social worker” rather than a writer – a shot at Harrower’s busy involvement in several people’s lives.

One of these involvements of nearly two decades was with Hazzard’s mercurially charming but very difficult mother, Kit Hazzard. The catalyst for the women’s letter-writing, Kit was eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder. It was Harrower, not Shirley or her sister Valerie (by now living near her mother), who organised the documents for Kit to receive the pension, located a psychiatrist for her, monitored the medications he prescribed, and visited Kit at home, in the psychiatric hospital and, eventually, the nursing home, having also organised the disposal of Kit’s flat.

Hazzard’s letters to Harrower contain “much love” and warm wishes, along with the gift of an all-expenses-paid holiday with the Steegmullers for Harrower’s loving attention to Kit.

Is this sense of responsibility for Kit, and others who received Harrower’s attention, what Harrower meant years later when she referred to the “self-sabotage” of her writing career? How could Hazzard and her sister Valerie let Harrower take responsibility for the wellbeing of their mother for so many years, especially as the stress of it all seemed to have been contributing to Harrower’s poor health?

These letters show that, along with the talent and disposition toward writing, a woman’s writing life can be made or unmade by luck as much as taking hard decisions. Hazzard had the steely skill for the latter and the financial means to uphold them.

White’s reference to Harrower as “social worker” was not his only allusion to the care she routinely provided her injured, unwell and unstable friends. Harrower was also involved in political activities that took her away from her writing. A member of the Australian Labor Party, she often acted as a conduit for writers and intellectuals seeking connections to federal and state governments and their cultural organisations during the short years of ALP power in the 1970s.

It is undecidable whether Harrower, discrete to the point of secrecy, was wilfully avoiding her writing vocation by these “social worker” involvements or temperamentally unable to make the hard decisions that Hazzard seems to have mastered.

We commonly expect friendships to be a democracy of two. With the writing lives of Hazzard and Harrower diverging so vastly during their years of correspondence, I wondered at certain points what was sustaining the friendship. Perhaps it was the letter writing itself, which enabled them to see, as if through a window, the life they might have lived if each had the other’s circumstances or temperament.

Linda Daley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.