The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission released its long-awaited proposal to require companies to disclose their climate risks to investors, and it’s arguably the most significant action on climate change yet under the Biden administration.

SEC Commissioner Allison Herren Lee called it a “watershed moment for investors and financial markets.” It is also a win for President Joe Biden, whose other climate efforts have struggled. A year ago, Biden appointed an SEC chairman, Gary Gensler, who supports climate disclosures in principle.

The proposed requirements, once finalized, could help climate-conscious investors more accurately direct their money to businesses that are responding to climate risks, simultaneously strengthening both markets and the nation’s climate response.

But the proposal has a long way to go before it can make the transformative changes it aims for. We study climate regulation and business law and have closely tracked debates over the proposal. Here’s what you need to know.

What the rule would do

If the SEC votes to finalize the rule after a public comment period, it would standardize, extend and mandate disclosure requirements that the SEC encouraged in a guidance document back in 2010.

As the 510-page notice released on March 21, 2022, makes clear, companies would be expected to include a laundry list of items in their regular filings with the SEC: information on the company’s “oversight and governance of climate-related risks,” any expected climate-related risks it faces in the future, any transition plans the business has developed, and data on certain greenhouse gas emissions linked to the company’s operations, among other things.

Gensler said the proposal draws from the approach of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure, which several countries have adopted. But the proposal is still noticeably less stringent than the European Union’s regulations.

In the leadup to the release of the SEC’s proposal, supporters and opponents speculated about whether so-called Scope 3 emissions would be required. Under the terms of the proposal, the answer is a resounding “maybe.”

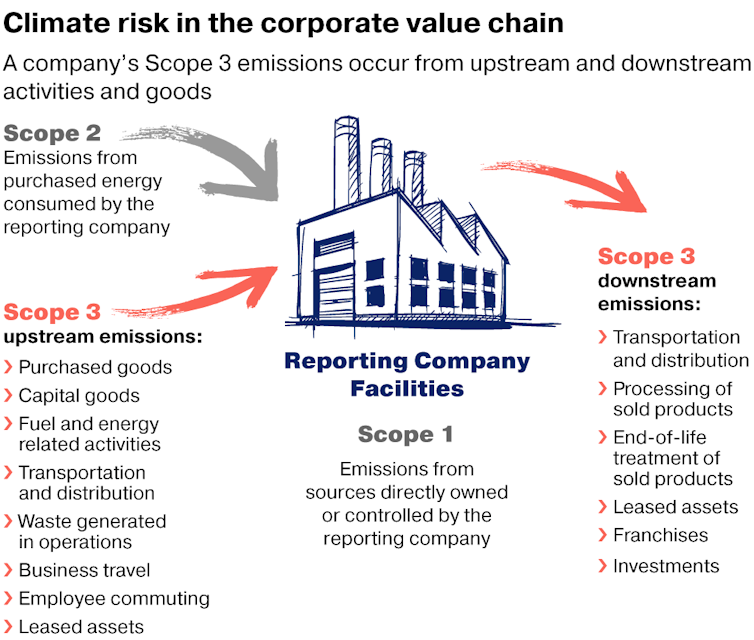

A company’s Scope 3 emissions result from activities of third parties, such as the emissions produced by its suppliers or, ultimately, by its consumers. As the SEC pointed out, these emissions can “represent a majority of the carbon footprint for many companies.”

While all registered companies would be required to disclose their own direct greenhouse emissions, such as emissions from manufacturing processes, as well as indirect emissions through the use of energy – Scopes 1 and 2, respectively – only some companies would need to report Scope 3 emissions under the proposal.

The proposal would exempt “small reporting companies” from Scope 3 reporting. It would allow large companies to withhold Scope 3 emissions data when the company determines that the data are not “material” to investors or if the company doesn’t have Scope 3 emissions targets or goals.

Public interest groups wanted the SEC to require disclosure of even non-material Scope 3 emissions, while industry groups pushed for the SEC to forgo any Scope 3 emissions mandate. The SEC appears to have split the baby.

It’s not over ‘til it’s over

The SEC’s proposal initiates what can be a perilous process of public vetting before the rule goes into effect.

First, the SEC will take public comments on the proposal for the next 60 days. The agency received about 600 unique comments in its request for information before issuing the proposal. Now, with more details available, there should be substantially more engagement. When the Federal Communications Commission took public comment on its proposal to roll back net neutrality rules, it received almost 22 million comments.

The SEC should expect to receive extensive comments both from opponents of any regulation and public interest groups that want more stringent regulations.

Under standard administrative law principles, the SEC must consider and respond to any important arguments or data presented by public commenters. If it gets even a fraction of the comments the FCC got, this process could easily take half a year.

By design, this process is supposed to allow the SEC to change the terms of the proposal, although it cannot change the proposal so much that the public would not have understood during the comment period what the final rule would do.

The courts lie in wait

Now that the terms of the proposed rule are in place, it is easier to see where legal vulnerabilities might be.

Industries are likely to take issue with the SEC’s estimates of the costs companies will face to comply with the rules. The SEC’s proposal states that the cost could be “relatively small” if companies already provide similar information. The SEC will have to defend that assertion carefully.

In 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia threw out an SEC rule on the grounds that it failed to adequately consider economic costs of compliance. Although that ruling has been widely criticized for imposing a cost-benefit analysis requirement that is not required by law, the U.S. Supreme Court seems sympathetic to such a requirement.

Another vulnerability will stem from the SEC’s approach to Scope 3 emissions.

Both industries and public interest groups are likely to argue that the SEC misunderstood its statutory authorization – either because it included Scope 3 emissions or because it believed it was limited to “material” emissions, respectively. Or challengers could argue that SEC failed to fully analyze policy considerations favoring a different approach. How well the SEC responds to critical comments will be important when the courts are asked to decide if the SEC acted in an arbitrary or capricious or unlawful manner.

Finally, it is possible that the matter is out of the SEC’s hands. Some critics have suggested that the regulation of climate disclosures is too important a question for regulators and belongs with Congress. Courts have sometimes shown skepticism toward agency actions that present so-called “major questions,” including those related to climate change.

If the courts view climate disclosure as a major question, they may vacate the rule even if the SEC has strongly supported its approach.

A long way to go

The SEC has taken a major step that could boost the Biden administration’s climate change agenda, but whether it will be able to navigate a treacherous administrative and legal process without changing its approach remains to be seen.

The notice of proposed rulemaking is usually just the opening offer in an ongoing negotiation over the rule.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.