At the wheel: scrappers patrolling the streets for discarded metal of all kinds.

They do it because even old, used metal — aluminum, steel, copper, brass — will bring a price.

Scrap-metal recycling is a multibillion-dollar industry. About 70% of the steel produced in this country is produced from scrap metal, according to Joseph Pickard, chief economist and director of commodities for the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries. Pickard says it’s cheaper and better for the environment to repurpose scrap metal rather than mine raw materials.

Metal scrappers play a small role in this huge supply chain. In the process, they help clear away potentially dangerous appliances and other metal rubbish that piles up in alleys and otherwise might end up in landfills.

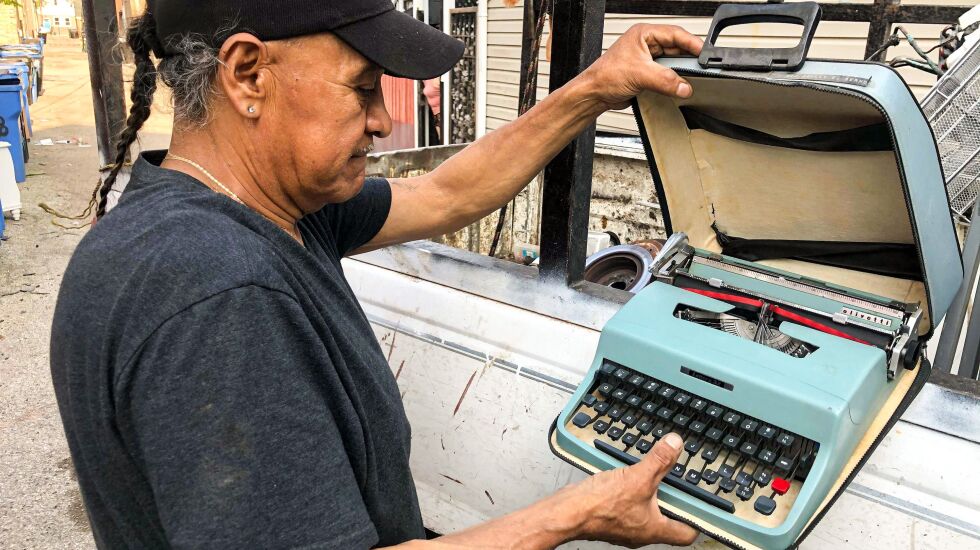

Francisco Garcia, a scrap-metal recycler from Pilsen, drives around in a truck decorated with dolls and mannequin heads, searching for scrap metal.

He spends at least six days a week scavenging. At 71, he still can jump onto the back of his truck to load an old grill or lift a boiler by himself. He keeps his long hair in a braid and often wears a black cap to protect his face from the sun.

He came to the United States from Mexico about 30 years ago and been metal-scrapping off and on for years.

He says he likes being his own boss, the schedule is flexible, and it pays the bills.

On average, Garcia says he makes about $60 a day. On a good day, he can make $100.

But he works hard for every cent.

He usually starts in Pilsen and drives through other nearby neighborhoods, like Chinatown, Bridgeport and Brighton Park.

“Wherever there is scrap metal, wherever the day takes us,” he says in Spanish.

Garcia can spot metal from a distance — old appliances, metal benches, electronics. He quickly dismisses mattresses and other items that look like metal but are made of plastic or wood.

Aside from finding the right objects, the amount of money he takes home depends on the global price of scrap metal each day.

Old refrigerators might sell for about $145 a ton. But collecting a ton is difficult, especially because a refrigerator has a lot of plastic parts.

Garcia also collects electric cords from fans and other appliances because they contain copper wire. He holds onto them until he gets enough. The price for clean copper wire can approach $4 a pound, depending on the type, according to iScrap, a phone app that lists rates for all types of scrap metal.

But that’s only if it’s stripped and cleaned, a time-consuming task. Garcia usually gets less for the wire he finds out on the streets.

Historically, metal-scrapping has beendone largely by immigrants, according to Carl Zimring, an environmental historian and professor of sustainability studies at the Pratt Institute in New York. Scrappers are often undocumented, speak limited English or can’t find other employment, he says.

Garcia says he doesn’t make enough to save after paying rent and other bills. At his age, he doesn’t have health insurance, savings or a retirement plan. He isn’t expecting Social Security, either. That’s the reality for many scrap-metal collectors who work independently.

Garcia worries about his financial security, especially because metal-scrapping is unpredictable. But he tries to stay positive.

“Dios aprieta pero no ahorca,” he says in Spanish: “God squeezes you but doesn’t choke you.”

Garcia rarely takes breaks when he’s hunting for scrap metal. After more than five hours of scavenging, his truck is piled high with rusty car engine parts, a heavy metal fence and a small refrigerator.

But he’s not ready to call it a day. He keeps driving through alleys.

Some people take a second look when he drives by. His truck is easy to spot. He has glued several mannequin heads to the roof. One has a long beard and a stylish haircut.

“Before, it had a braid,” he says in Spanish.

He’s thinking about giving the mannequin a trim.

His truck is also decorated with dolls hanging from the sides. He spots a few stuffed animals in an alley near garbage cans — a Teddy bear here, a gorilla there. But he likes the spooky kind of dolls, he says.

The struggles Garcia faces as a metal scrapper aren’t just economic. He and other collectors also deal with serious safety hazards, Zimring says.

“If you’re, say, collecting an old washing machine, it’s going to be heavy, you might cut it up to put it in your vehicle,” Zimring says. “But, of course, in doing so, you might expose yourself to wounds, you might expose yourself to tetanus.”

Garcia knows those dangers. He often has to cut metal with a grinder, drain the contaminants from old appliances and lift extremely heavy equipment — without any worker protections.

Near the end of this day, he finds some thick, rusty metal beams. He starts cutting them, creating sparks. He does not have goggles to protect his eyes. He says he’s more cautious than many metal scrappers — not everyone can afford the right equipment to clean and cut metal.

Experts like Zimring, who has been a board member of the Chicago Recycling Coalition, say this work could be made much safer with better regulations and more protections for workers. Chicago could, for instance, expand its Sanctuary City ordinance to guarantee basic rights for freelance scrap-metal collectors and other vulnerable workers.

Zimring also says the city needs to have better oversight of scrap-metal recycling businesses, making sure they follow environmental laws and keep buildings up to code.

Zimring and other environmentalists are critical of metal recycling businesses that buy scrappers’ metal. They say metal shredding is noisy and can disturb neighbors and that some facilities have piles of hazardous materials that create fire risks and the potential for air-polluting smoke and dust. And many of them are in South Side and West Side neighborhoods close to homes, schools and parks.

But some yard owners say they are providing an important service that contributes to the reuse of materials.

Garcia understands the differing viewpoints. He knows the work is dangerous, both in the alleys and at the scrap recycling yards. But he relies on those businesses to buy the metal he collects.

“It’s hard, it’s very hard,” he says in Spanish. “If we don’t know how to protect ourselves, we can get seriously hurt, get bruises, cuts, hurt our backs. We don’t know if we are gonna be able to make it out the next day.”