Every day, new species discoveries make big headlines in the news, but scientists are also realizing just how many “undiscovered” species are hiding in plain sight.

These species lie buried within scientific classification — known as Linnaean taxonomy — and are often lumped together with other animals or plants when they really ought to be classified as their own species.

But a new study examining fruit species in the Malaysian Borneo and the Philippines suggests researchers can learn from existing Indigenous knowledge to formally identify these species and bring them into the scientific realm. The findings were published Monday in the journal Current Biology.

“There are likely other species recognized by indigenous people but not yet recognized by science, and that is one of the reasons that we feel it is important for scientists to engage with indigenous knowledge,” Elliot Gardner, lead author of the study and a researcher of tropical plants at Florida International University, tells Inverse.

Here’s the background — In the gardens of homes in Borneo and the Philippines, it’s not uncommon to find a cultivated sweet fruit tree with thick pulp that bears a strong resemblance to jackfruit and breadfruit. The official scientific name for this tropical plant is A. odoratissimus, though locals refer to the plant by more colloquial names like marang and tarap.

An eighteenth-century Spanish friar who researched botanical plants in the Philippines, Manuel Blanco, was the first person to formally describe A. odoratissimus. Nineteenth-century Italian botanist, Odoardo Beccari, also later described two mature fruit specimens that scientists associate with A. odoratissimus.

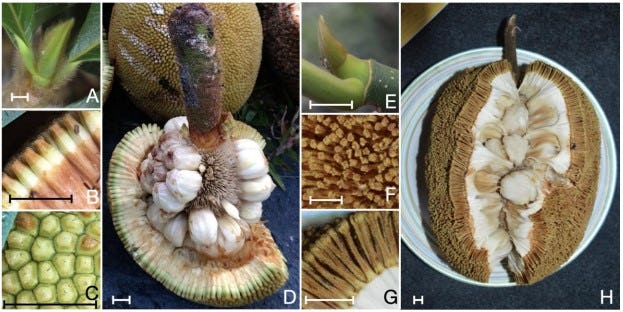

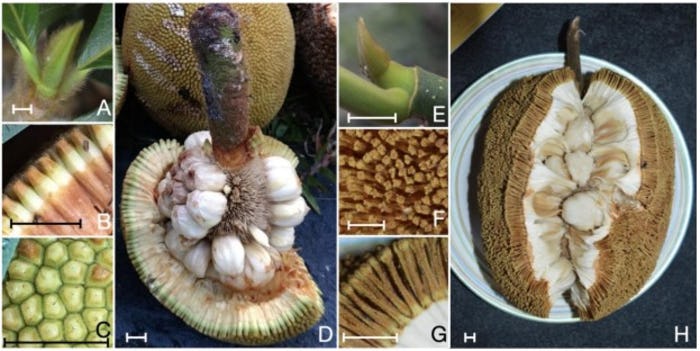

Botanists also knew a wild relative of this tree existed that was somewhat different from the domesticated variety, but scientists simply thought it was a variant of the same species. The wild relative contained smaller, less-sweet fruits with thinner pulp and longer hairs.

But unbeknownst to scientists, Indigenous communities in Borneo and the Philippines had long classified A. odoratissimus as not one species, but two clearly separate species, with each fruit tree clearly marked by distinct features.

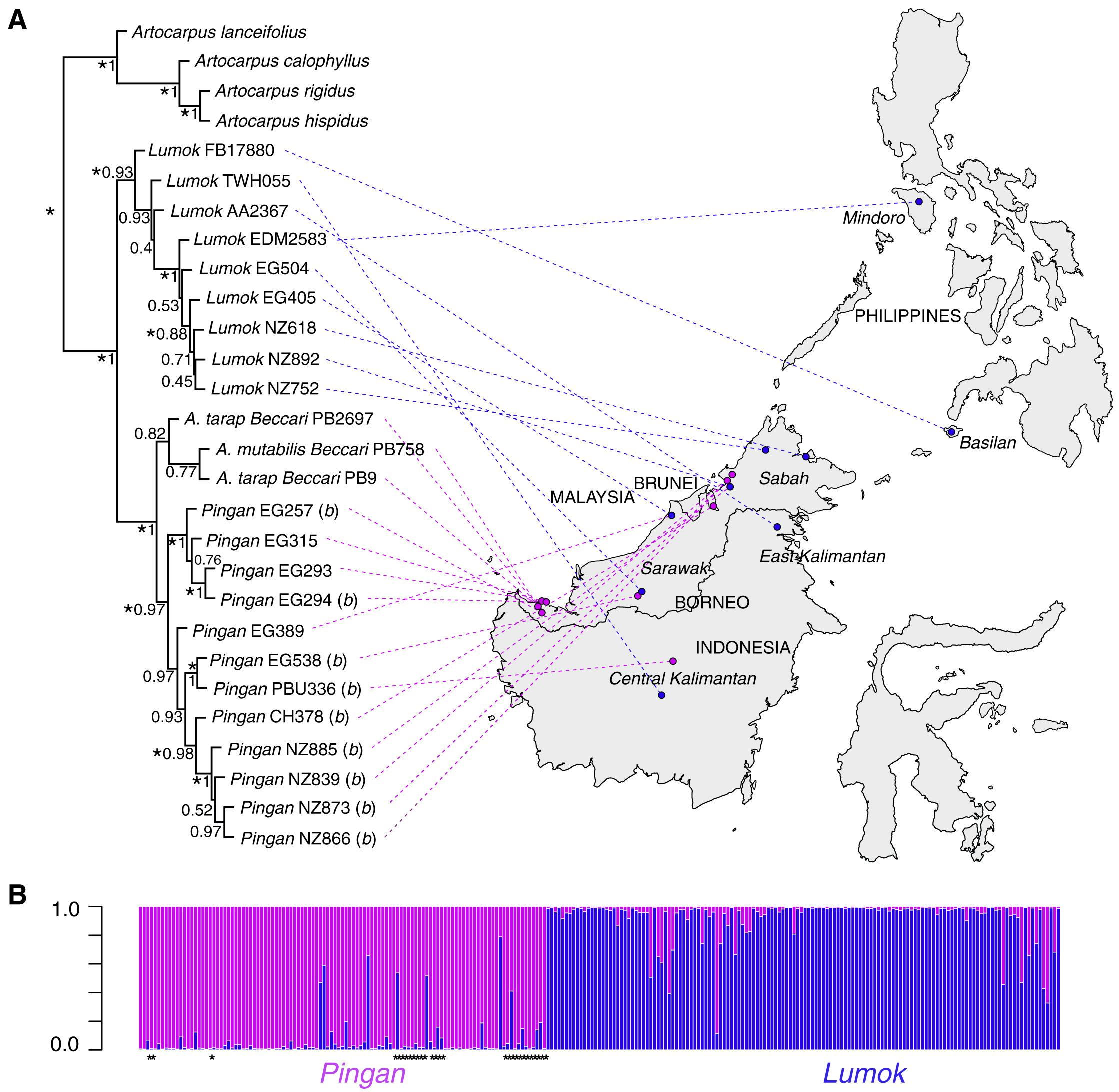

The Iban people in Sarawak — a Malayasian state in Borneo — recognized the cultivated and wild varieties of the plant as two species: lumok (cultivated) and pingan (wild). The Dusun people of Sabah — another state in Borneo — similarly recognized these plants as separate species known as timadang (cultivated) and tonggom-onggom (wild).

“I think that scientists working on these plants were not aware of the Indigenous classification system, because scientists have not often engaged with that type of knowledge,” Gardner says.

What’s new — In this latest study, Gardner’s team set out to bridge the gap between scientific and Indigenous knowledge. Specifically, they sought to scientifically verify whether these two plants, were, indeed, two genetically distinct species.

Through their research, the scientists confirmed the traditional knowledge of the Dusun and the Iban: The wild pingan is genetically distinct from the domestically cultivated plant lumok.

“The plants have noticeably different fruits which were evident to Indigenous people who were constantly around the plants but were not evident to scientists working largely from preserved specimens,” Gardner says.

With this study, science now formally recognizes and validates pingan as its own separate species. Therefore, pingan needs a scientific name so it can fit with the Linnaean taxonomy, the standard of scientific classification which Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus established in the 1700s. Gardner’s team settled on A. mutabilis, a reference to the Italian botanist Beccari’s research on the plants in 1885.

How they made the discovery — In 2013, the researchers began their fieldwork in the Malaysian state of Sabah in Borneo before expanding to other areas. Gardner was intrigued by the unique plant, A. odoratissimus, especially for its delicious taste.

“We wondered whether there were any genetic differences between cultivated and wild plants,” Gardner says.

But the scientists really honed in on the Indigenous distinctions between the two plants in 2017, when they started collecting plant samples with two Iban field botanists, Jugah anak Tagi and Salang anak Nyegang, who are also co-authors on the study. Their collaborators from the state of Sabah in Borneo, field botanists Postar Miun and Jeisin Jumian, also confirmed that the Indigenous Dusun recognize the plants as two separate species.

“These findings led us to realize the importance of considering indigenous vernacular names in thinking about species limits,” Gardner says.

So, Gardner’s team used genetic sequencing to confirm the Indigenous classification of these two plants. Using field samples collected from Borneo, the scientists deployed a method known as target capture, which enriches DNA and allows researchers to efficiently sequence genes from the plant. This method allowed them to analyze the Italian botanist Beccari’s botanical samples from the 1800s, comparing them to modern plants.

“Because the target regions do not need to be on intact fragments, this method is suitable even for old samples with degraded DNA,” Gardner says.

Using these methods, the scientists were able to confirm there were “two distinct genetic clusters” for lumok and pingan.

Why it matters — The study’s publication is timely as scientists are collaborating more with Indigenous communities on projects ranging from gauging wildfire risk to sucking forever chemicals — chemicals known as “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances” that linger in the environment for years — out of the ground. With this new study, we can add another area of scientific research where Indigenous knowledge will prove invaluable: species classification.

“People who live close to plants and see them on a daily basis have a different kind of knowledge about them that is different from and complements the way scientists think about plants,” Gardner says.

What’s next — To best protect a species, researchers must classify it scientifically within the Linnaean taxonomy. To conserve a species, scientists must name it, otherwise, it won’t appear on the IUCN Red List — the official list of plants and animals that conservation organizations use to classify endangered and threatened species.

But current scientific classification is lacking, and we can partner with Indigenous communities to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of species, the study argues.

“While Linnaean taxonomy offers a broad framework for global comparisons, it may lack the detailed local insights possessed by indigenous peoples,” the study authors write.

By marrying scientific knowledge with Indigenous classifications, we could potentially protect species from extinction. Due to manmade trends like global warming and deforestation, species are disappearing nearly every day. The UN reported in 2019 that one million animal and plant species faced extinction.

Gardner says that scientists are often already working with Indigenous guides when they conduct fieldwork, so it would be a natural next step for researchers and Indigenous communities to collaborate to classify species.

“This kind of collaboration can improve our understanding of biodiversity and can improve recognition of the contributions Indigenous people have been making to science all along,” Gardner says.